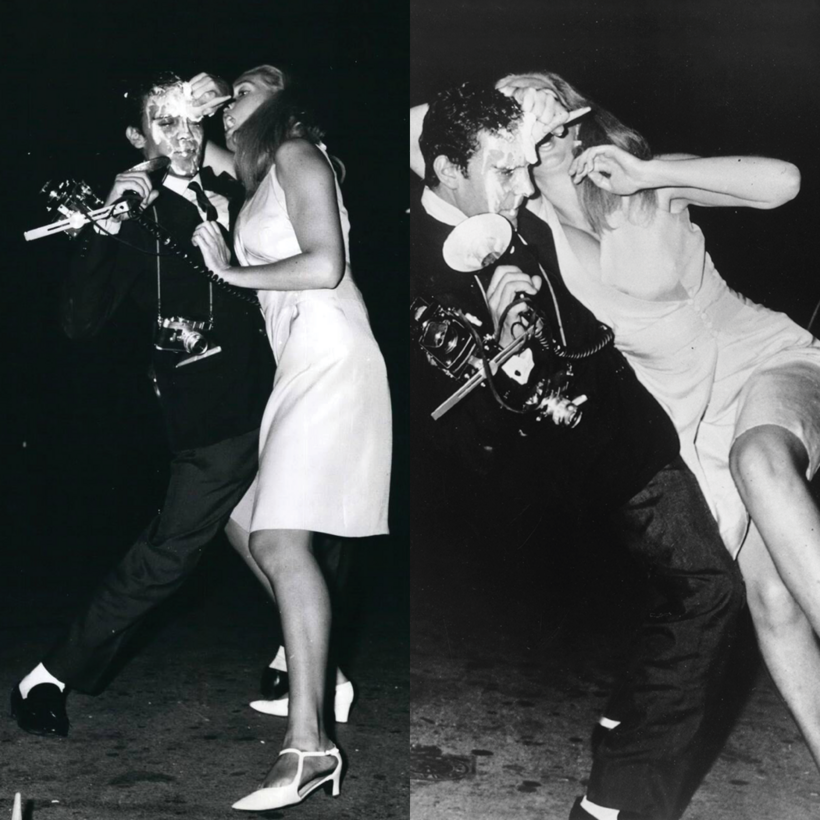

The King of Paparazzi is immaculately turned out as he welcomes me into his apartment: black suit with breast pocket handkerchief, black shiny shoes and white shirt, his usual attire as he prowls the streets of Rome looking for celebrities.

“I dress like this to show respect to the people I photograph,” says Rino Barillari, 79.