“Have you seen Esquire?! Call me as soon as you’re finished,” New York society doyenne Babe Paley asked her friend Slim Keith over the telephone when the November 1975 issue hit the stands. Keith, then living at the Pierre hotel, sent the maid downstairs for a copy. “I read it, and I was absolutely horrified,” she later confided to the writer George Plimpton. “The story about the sheets, the story about Ann Woodward … There was no question in anybody’s mind who it was.”

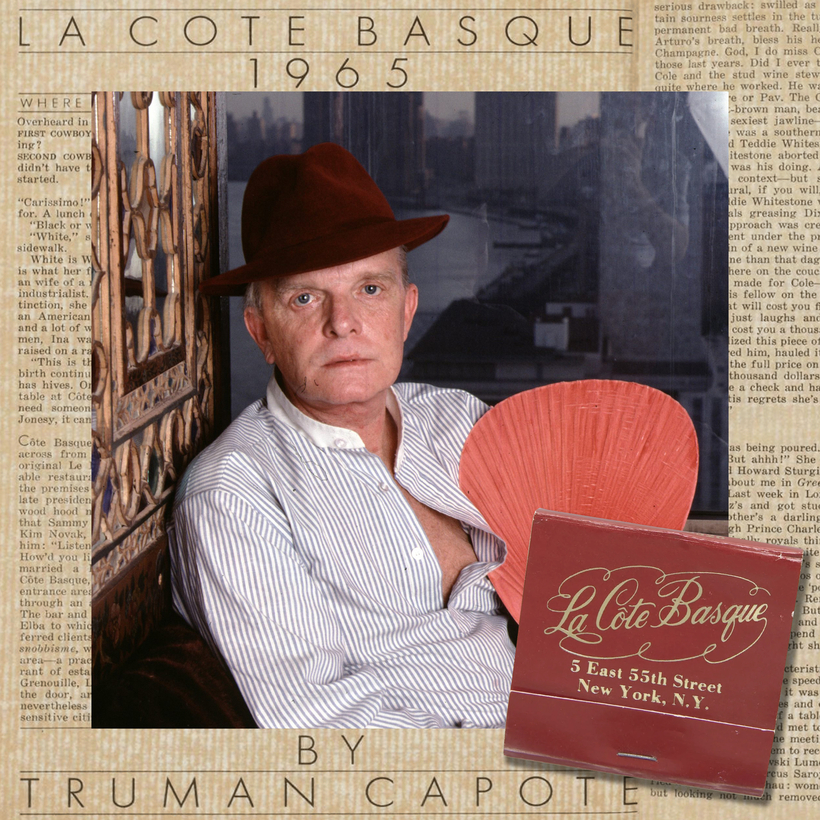

The story they were reading in Esquire was “La Côte Basque 1965,” but it wasn’t so much a story as an atomic bomb that Truman Capote built all by himself in his U.N. Plaza apartment and at his beach house in Sagaponack, Long Island. It was the first installment of Answered Prayers, the novel that Truman believed would be his masterpiece.

He had boasted to his friend Marella Agnelli, wife of Gianni Agnelli, chairman of the board at Fiat, that Answered Prayers was “going to do to America what Proust did to France.” He couldn’t stop talking about his planned roman à clef.

He told People magazine that he was constructing his book like a gun: “There’s the handle, the trigger, the barrel, and, finally, the bullet. And when that bullet is fired from the gun, it’s going to come out with a speed and power like you’ve never seen—wham!”

But he had unwittingly turned the gun on himself: exposing the secrets of Manhattan’s rich and powerful was nothing short of social suicide.

He had been a literary darling since the age of 23, when his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, was published. Seventeen years later, in 1965, In Cold Blood, his extraordinary “nonfiction novel” about the brutal murder of the Clutters, a Kansas farm family, brought him international fame, sudden wealth, and literary accolades beyond anything he’d experienced before.

But trying to write Answered Prayers, and its eventual fallout, destroyed him. By 1984, after several unsuccessful stays at dry-out centers such as Hazelden and Smithers, Capote seemed to have given up not only on the book but on life. Abandoned by most of his society friends, locked in a brutal, self-destructive relationship with a middle-aged, married former bank manager from Long Island, Truman was worn out. Or heartbroken.

After “La Côte Basque 1965,” only two more of its chapters were published, both in Esquire: “Unspoiled Monsters” (May 1976) and “Kate McCloud” (December 1976). (“Mojave,” which had appeared in Esquire in June 1975, was initially intended to be part of Answered Prayers, but Truman changed his mind about its inclusion.)

Truman had recorded in his journals the outline for the entire book, which would comprise seven chapters. The remaining four were titled “Yachts and Things,” “And Audrey Wilder Sang,” “A Severe Insult to the Brain” (which according to urban legend was the cause of death on Dylan Thomas’s death certificate), and “Father Flanagan’s All-Night [N*****] Queen Kosher Café,” the provocative title for the teeth-rattling concluding chapter. Truman claimed in his journals he had actually written it first.

But was the novel ever completed? A number of Truman’s friends, including Joanne Carson (the second wife of television host Johnny Carson), say that he had read various unpublished chapters to them. “I saw them,” Joanne recalled. “He had a writing room in my house—he spent a lot of time here because it was a safe place and nobody could get to him—and he had many, many pages of manuscript, and he started to read them. They were very, very good. He read one chapter, but then someone called, and when I went back he just put them aside and said, ‘I’ll read them after dinner.’ But he never did—you know how that happens.” (Joanne died in 2015.)

Capote said he was constructing his book like a gun: “There’s the handle, the trigger, the barrel, and, finally, the bullet. And when that bullet is fired from the gun, it’s going to come out with a speed and power like you’ve never seen—wham!”

After Capote’s death, on August 25, 1984, just a month shy of his 60th birthday, Alan Schwartz (his lawyer and literary executor), Gerald Clarke (his friend and biographer), and Joe Fox (his Random House editor) searched for the manuscript of the unfinished novel. Random House wanted to recoup something of the advances it had paid Truman—even if that involved publishing an incomplete manuscript. (In 1966, Truman and Random House had signed a contract for Answered Prayers for an advance of $25,000, with a delivery date of January 1, 1968. Three years later, they renegotiated to a three-book contract for an advance of $750,000, with delivery by September 1973. The contract was amended three more times, with a final agreement of $1 million for delivery by March 1, 1981. That deadline passed like all the others with no manuscript being delivered.)

Following Capote’s death, Schwartz, Clarke, and Fox searched Truman’s apartment, on the 22nd floor of the U.N. Plaza, with its panoramic view of Manhattan and the United Nations. It had been bought by Truman in 1965 for $62,000 with his royalties from In Cold Blood. (A friend, the set designer Oliver Smith, noted that the U.N. Plaza building was “glamorous, the place to live in Manhattan” in the 1960s.) The three men looked among the stacks of art and fashion books in Capote’s cluttered Victorian sitting room and pored over his bookshelf, which contained various translations and editions of his works. They poked among the Tiffany lamps, his collection of paperweights (including the white rose paperweight given to him by Colette in 1948), and the dying geraniums that lined one window (“bachelor’s plants,” as writer Edmund White described them). They looked through drawers and closets and desks, avoiding the three taxidermic snakes Truman kept in the apartment, one of them, a cobra, rearing to strike.

The men scoured the guest bedroom, at the end of the hallway—a tiny peach-colored room with a daybed, a desk, a phone, and lavender taffeta curtains. Then they descended 15 floors to the former maid’s studio, where Truman had often written by hand on yellow legal pads.

“We found nothing,” Schwartz said. Joanne Carson claimed that Truman had confided to her that the manuscript was tucked away in a safe-deposit box in a bank in California—maybe Wells Fargo—and that he had handed her a key to it the morning before his death. But he declined to tell her which bank held the box. “The novel will be found when it wants to be found,” he told her cryptically.

The three men then traveled to Truman’s rustic beach house, tucked away behind scrub pine, privet hedges, and hydrangea, on six acres, in Sagaponack. They enlisted the help of two of Truman’s closest friends in later years, Joe Petrocik and Myron Clement, who ran a small P.R. firm and had a house in nearby Sag Harbor.

“He was just a wonderful person to us, a great friend,” Clement recalls. “Truman would talk to us about all these things that were going into Answered Prayers,” says Petrocik. “I remember I was at the other end of his couch, and he’s reading all this from a manuscript. Then he’d take a break, get up, and pour himself a Stoli. But the thing is, at that time, I never saw the actual manuscript. And then it occurred to me, later, just before I nodded off to sleep, maybe he had made the whole thing up. He was such a wonderful, wonderful actor.”

Later on, though, Petrocik remembers, he was traveling with Truman from Manhattan to Long Island when “Truman handed me the manuscript to read on the way. I actually had it in my hands.”

But after a thorough search of the beach house, no manuscript was found. Now, nearly 30 years later, the questions remain: What happened to the rest of Answered Prayers? Had Truman destroyed it, simply lost it, or hidden it, or had he never written it at all? And why on earth did he publish “La Côte Basque 1965” so early, considering the inevitable backlash?

Gerald Clarke, author of the masterful Capote: The Biography, recalls Truman telling him, in 1972, “I always planned this book as being my principal work.... I’m going to call it a novel, but in actual fact it’s a roman à clef. Almost everything in it is true, and it has … every sort of person I’ve ever had any dealings with. I have a cast of thousands.”

He had begun thinking about it as early as 1958 and wrote a complete outline, and even an ending. He also wrote part of a screenplay that year with the title Answered Prayers, about a manipulative southern gigolo and his unhappy paramour. Though the screenplay was apparently abandoned, the idea took shape as a lengthy, Proustian novel. The title is taken from St. Teresa of Ávila, the 16th-century Carmelite nun, who famously said, “More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.”

In a letter to Random House publisher and co-founder Bennett Cerf, written from Páros, Greece, in the summer of 1958, Truman promised that he was in fact working on “a large novel, my magnum opus, a book about which I must be very silent.... The novel is called, ‘Answered Prayers’; and, if all goes well, I think it will answer mine.” But before he could write it, another work took over Truman’s life: In Cold Blood. Begun in 1959, it would consume six years of his life—most of it spent living in Kansas, a world away from the New York society he loved and from the city where he felt he belonged.

The Cat That Ate the Canary

In “La Côte Basque 1965,” Capote turned his diamond-brilliant, diamond-hard artistry on the haut monde of New York society fixtures: Gloria Vanderbilt, Babe Paley, Slim Keith, Lee Radziwill, Mona Williams—elegant, beautiful women he called his “swans.” They were very soignée and very rich and also his best friends. In the story Capote revealed their gossip, the secrets, the betrayals—even a murder. “All literature is gossip,” Truman told Playboy magazine after the controversy erupted. “What in God’s green earth is Anna Karenina or War and Peace or Madame Bovary, if not gossip?”

The story was intended to be the fifth chapter of the book, its title referring to Henri Soulé’s celebrated restaurant, on East 55th Street, across from the St. Regis hotel. It was where the swans gathered to lunch and to see and be seen. In the story a literary hustler and bisexual prostitute named P. B. Jones—“Jonesy”—runs into “Lady Ina Coolbirth” on the street. A much-married-and-divorced society matron, she has been stood up by the Duchess of Windsor, so she invites Jonesy to join her for lunch at one of the coveted tables at the front of the restaurant. Lady Coolbirth, in Truman’s words, is “a big breezy peppy broad” from the American West, now married to an English aristocrat. If she had looked in the mirror, she would have seen Slim Keith, who had been well and often married, to film director Howard Hawks and film and theatrical producer Leland Hayward before wedding the English banker Sir Kenneth Keith.

The story unfolds as a long, gossipy conversation—a monologue, really—delivered by Lady Coolbirth over countless flutes of Roederer Cristal champagne. She observes the other ladies who lunch—Babe Paley and her sister Betsey Whitney; Lee Radziwill and her sister, Jacqueline Kennedy; and Gloria Vanderbilt and her friend Carol Matthau. Or, as Capote wrote, “Gloria Vanderbilt de Cicco Stokowski Lumet Cooper and her childhood chum, Carol Marcus Saroyan Saroyan (she married him twice) Matthau: women in their late thirties, but looking not much removed from those deb days when they were grabbing Lucky Balloons at the Stork Club.” Other boldfaced names who appear undisguised include Cole Porter coming on to a handsome Italian waiter; Princess Margaret, who makes snide comments about “poufs”; and Joe Kennedy, jumping into bed with one of his daughter’s 18-year-old school chums.

Lady Coolbirth grouses about having got stuck at a dinner next to Princess Margaret, who bored her into semi-unconsciousness. As for Gloria Vanderbilt, Capote presents her as empty-headed and vain, especially when she fails to recognize her first husband, who stops by her table to say hello. (“‘Oh, darling. Let’s not brood,’ says Carol consolingly. ‘After all, you haven’t seen him in over twenty years.’”) When Vanderbilt read the story, she supposedly said, “The next time I see Truman Capote, I’m going to spit in his face.”

“I think Truman really hurt my mother,” the CNN journalist and newscaster Anderson Cooper says today.

They were very soignée and very rich and also his best friends. In the story Capote revealed their gossip, the secrets, the betrayals—even a murder.

But the tale that spread like a prairie fire up Park Avenue was a thinly disguised account of a humiliating one-night stand endured by “Sidney Dillon,” a stand-in for William “Bill” Paley, the head of the CBS television-and-radio network and one of the most powerful men in New York at that time. Bill and Truman were friends, but Truman worshipped his wife, Barbara “Babe” Paley—the tall, slim, elegant society doyenne widely considered to have been the most beautiful and chic woman in New York. Of Truman’s haut monde swans, Babe Paley was the most glamorous. Truman once noted in his journals, “Mrs. P had only one fault: she was perfect; otherwise, she was perfect.” The Paleys practically adopted Truman; photographs of the three of them at the Paleys’ house in Jamaica show the tall, handsome couple with tiny Truman standing beside them, wearing swimming trunks and a cat-that-ate-the-canary smile, as if he were their pampered son.

The one-night stand in the story occurs between Dillon and the dowdy wife of a New York governor, possibly based on Nelson Rockefeller’s second wife, Mary, known by her nickname “Happy.” She was “a cretinous Protestant size forty who wears low-heeled shoes and lavender water,” Truman cattily wrote, who “looked as if she wore tweed brassieres and played a lot of golf.” Though married to “the most beautiful creature alive,” Dillon desires the governor’s wife because she represents the only thing that lies outside of Dillon’s grasp—acceptance by old-money WASP society, a plum denied Dillon because he is Jewish. Dillon sits next to the governor’s wife at a dinner party, flirts with her, and invites her up to his New York pied-à-terre, at the Pierre, saying he “wanted her opinion of his new Bonnard.” After they have sex, he discovers that her menstrual blood has left a stain “the size of Brazil” on his bedsheet. Worried that his wife will arrive at any moment, Dillon scrubs the sheet in the bathtub, on his hands and knees, and then attempts to dry it by baking it in the oven before replacing it on the bed.

Within hours of the story’s publication in Esquire, frantic phone calls were made all over the Upper East Side. Slim called back Babe, who asked of the Sidney Dillon character, “You don’t think that it’s Bill, do you?”

“Of course not,” Slim lied, but she had heard from Truman months earlier that indeed it was Bill Paley.

Babe was horrified and heartbroken. She was seriously ill at the time with terminal lung cancer, and, instead of blaming her husband for the infidelity, she blamed Truman for putting it into print. Sir John Richardson, the acclaimed Picasso biographer, saw her often during the last months of her life. “Babe was appalled by ‘La Côte Basque,’” he recalled. “People used to talk about Bill as a philanderer, but his affairs weren’t the talk of the town until Truman’s story came out.” (Richardson died in 2019.)

Babe would never speak to Truman again.

But her response paled compared with the reaction of another one of Truman’s subjects: Ann Woodward. She had achieved notoriety for having shot and killed her husband 20 years earlier, but the story had been largely forgotten before “La Côte Basque 1965” was published. Woodward—Ann Hopkins in Truman’s story—enters the restaurant, creating an immediate stir; even the Bouvier sisters, Jacqueline and Lee, take note. In Truman’s retelling of the saga, Ann is a beautiful redhead from the West Virginia hills whose Manhattan odyssey had taken her from call girl to “the favorite lay of one of [gangster] Frankie Costello’s shysters” to—ultimately—the wife of David Hopkins (William Woodward Jr.), a handsome young scion of wealth and “one of the bluest of New York’s blue bloods.” Ann is another of the many Holly Golightly figures who make their appearances throughout Truman’s oeuvre—beautiful, social-climbing waifs from the rural South who move to New York and re-invent themselves, not unlike Truman’s own personal journey. But Ann continued to philander, and David—eager to divorce her—discovered that she had failed to dissolve a teenage marriage undertaken back in West Virginia, and thus they weren’t legally married after all. Terrified that he will kick her out, Ann takes advantage of a rash of break-ins in the neighborhood and loads a shotgun, which she keeps beside her bed. She fatally shoots David, claiming that she mistook him for an intruder. Her mother-in-law, Hilda Hopkins (Elsie Woodward), desperate to avoid a scandal, pays off the police, and an inquest never brings charges against Ann for murder.

On October 10, 1975, just a few days before the November Esquire appeared, Ann Woodward was found dead. Many believed that someone had sent her an advance copy of Truman’s story and she’d killed herself, by swallowing cyanide. “We’ll never know, but it’s possible that Truman’s story pushed her over the edge,” says Clarke. “Her two sons later committed suicide as well.” Ann’s mother-in-law grimly said, “Well, that’s that. She shot my son, and Truman murdered her … ”

When Gloria Vanderbilt read the story, she supposedly said, “The next time I see Truman Capote, I’m going to spit in his face.”

Luckily for Truman he was able to hightail it out of town when “La Côte Basque 1965” was published, to begin rehearsals for his first starring role in a film, Columbia Pictures’ 1976 comedy Murder by Death, produced by Ray Stark. Accompanied by John O’Shea, his middle-aged bank-manager lover from Wantagh, Long Island, Truman rented a house at 9421 Lloydcrest Drive, in Beverly Hills. The murder-mystery spoof, written by Neil Simon and directed by Robert Moore, cast a number of great comic actors in roles parodying famous detectives—Peter Falk as Sam Diamond (Sam Spade), James Coco as Milo Perrier (Hercule Poirot), Peter Sellers as Sidney Wang (Charlie Chan), Elsa Lanchester as Miss Marbles (Miss Marple), and David Niven and Maggie Smith as Dick and Dora Charleston (Nick and Nora Charles). Alec Guinness played a blind butler (as in “the butler did it”), and Truman played Mr. Lionel Twain, an eccentric connoisseur of crime. It was supposed to be great fun, but Truman found working on Murder by Death to be grueling. O’Shea recalled that “he used to get up in the morning as if he were going to the gallows, instead of the studio.”

Though his screen time was quite brief, he crowed to a visiting journalist on the set of Murder by Death in Burbank, “What Billie Holiday is to jazz, what Mae West is to tits … what Seconal is to sleeping pills, what King Kong is to penises, Truman Capote is to the great god Thespis!” In reality he was not much of an actor, and he looked bloated and unwell on-screen. The reviews were not kind.

While in Los Angeles, Truman spent much of his time at Joanne Carson’s Malibu house. She stood by helplessly while he rattled around, still stunned by the reaction to “La Côte Basque 1965.” He complained to Joanne, “But they know I’m a writer. I don’t understand it.”

To café society, his departure from New York looked like pure cowardice. He phoned Slim Keith, whom he often called “Big Mama,” but she refused to talk to him. Unable to accept Slim’s rejection, he boldly sent her a cable in Australia at the end of the year, where she was spending the holidays: “Merry Christmas, Big Mama. I’ve decided to forgive you. Love, Truman.” Far from forgiving him, Slim had consulted a lawyer about suing Truman for libel. But what really broke his heart was the reaction from the Paleys.

Screwing up his courage, Truman phoned Bill Paley, who took the call. Paley was civil but distant, and Truman had to ask if he’d read the Esquire story. “I started, Truman,” he said, “but I fell asleep. Then a terrible thing happened: the magazine was thrown away.” Truman offered to send him another copy. “Don’t bother, Truman. I’m preoccupied right now. My wife is very ill.” Truman was devastated by those words—“my wife”—as if his wife weren’t Babe Paley, a woman whom Truman idolized and whose friendship he had long treasured. Now she was mortally ill, and he wasn’t even allowed to speak to her.

Babe died in the Paleys’ Fifth Avenue apartment on July 6, 1978. Truman was not invited to the funeral. “The tragedy is that we never made up before she died,” he told Gerald Clarke years after her death.

Society’s Sacred Monsters

“Truman’s ‘Côte Basque’ was all anybody was talking about,” columnist Liz Smith remembers. She was asked by Clay Felker, the editor of New York magazine, to interview him. “Truman was thrilled that I was going to do it. I went to Hollywood to interview him. I’ll never forget how distraught he was because the pressure was building. In the Padrino bar, in the Beverly Wilshire, he said, ‘I’m going to call [former Vogue editor] Mrs. Vreeland, and you’ll see that she’s really on my side.’ So he caused a big ruckus and they brought a phone [to the table]. He called her. He said, ‘I’m sitting here with Liz Smith, and she tells me that everyone is against me, but I know you’re not.’ He went on and on, holding the phone out for me to hear.” Vreeland spouted a series of inscrutable responses—“meaning everything and nothing—but Truman didn’t get the vote of confidence he was hoping for.”

Smith came away worried about Truman, “because it seemed as if he was going to go all to pieces. He was the most surprised and shocked person you can imagine, and he would call to ask me—torment me—about what people in New York had said about him. After ‘La Côte Basque’ he was never happy again.”

Smith’s ensuing article, “Truman Capote in Hot Water,” ran in the February 9, 1976, issue of New York. “Society’s sacred monsters at the top have been in a state of shock,” Smith wrote. “Never have you heard such gnashing of teeth, such cries for revenge, such shouts of betrayal and screams of outrage.” In her article Smith outed those swans Truman had bothered to thinly disguise: Lady Coolbirth was Slim Keith; Ann Hopkins was Ann Woodward; Sidney Dillon was Bill Paley. “It’s one thing to tell the nastiest story in the world to all your fifty best friends,” Smith wrote. “It’s another to see it set down in cold, Century Expanded type.”

And not only did the swans turn against him, their husbands did as well, even if they weren’t mentioned in the story. Louise Grunwald, who had worked at Vogue before she married Henry Grunwald, the editor in chief of Time Inc. magazines, noticed that Truman’s friendships with women would not have flourished had he not also charmed their husbands. “Most men of that era,” she recalls, “were homophobic—very homophobic. But Truman was their exception, because he was so amusing. Nobody came into their houses that the husbands didn’t approve of. In a way, Truman could be very seductive, and he was a good listener. He was sympathetic. He seduced both the men and the women.”

A few days before the November Esquire appeared, Ann Woodward was found dead. Many believed that someone had sent her an advance copy of Truman’s story and she’d killed herself, by swallowing cyanide.

But as the scandal unfolded, “Are you seeing Truman or are you not?” was whispered throughout New York’s high society. Slim Keith would run into him occasionally at the restaurant Quo Vadis, on East 63rd Street between Madison and Park Avenues, but she “never looked up at his face again,” Keith bragged to George Plimpton. Ostracizing Truman became the thing to do. “In the long run, the rich run together, no matter what,” Truman said in a 1980 Playboy-magazine interview. “They will cling, until they feel it’s safe to be disloyal, then no one can be more so.”

At least Lee Radziwill and Carol Matthau, who did not come off badly in “La Côte Basque 1965,” stood up for Truman. Radziwill felt that it was Truman who had been “taken advantage of by a lot of people he thought were his friends. After all, he was fun and interesting to talk to, and brilliant. Why wouldn’t they want to have him around? He was absolutely in shock” about café society’s reaction, she recalls. “He’d hear of another monument falling, and he’d say, ‘But I’m a journalist—everybody knows that I’m a journalist!’ I just don’t think he realized what he was doing, because, God, did he pay for it. That’s what put him back to serious drinking. And then, of course, the terrible fear that he could never write another word again. It was all downhill from then on.”

“Unspoiled Monsters” appeared next. It’s a mordantly funny, hair-raising, but deeply cynical account of a fictional writer named P. B. Jones (the P.B. standing for Paul Bunyan, Capote noted in his journals), who is the Jonesy in “La Côte Basque 1965.” It’s a far cry from the honeysuckle lyricism of Capote’s earlier work, or the stark reportage of In Cold Blood; it tells the picaresque tale of young Jones, the gay hustler who beds men and women alike if they can further his literary career. Katherine Anne Porter makes a disguised appearance, as does Tennessee Williams, both in cruel caricatures. Like Truman, Jones is writing a novel called Answered Prayers, even using the same Blackwing pencils Truman favored. He’s a charming but hard-bitten male version of Holly Golightly, having escaped a Catholic orphanage to flourish in New York. His impoverished past, Truman later confided, was borrowed from the life story of Perry Smith, the dark-haired, dark-eyed murderer Truman came to know intimately while writing In Cold Blood. In a sense, P. B. Jones is both Truman and Perry, a figure who haunted Truman’s last decade and whose execution by hanging—which Truman witnessed—would devastate him emotionally.

The title character of “Kate McCloud,” which followed in Esquire, was modeled on Mona Williams, later Mona von Bismarck, another oft married socialite friend of Truman’s whose cliff-top villa on Capri he’d visited. Of Mona’s five husbands, one, James Irving Bush, was described as “the handsomest man in America” and another, Harrison Williams, as “the richest man in America.” Also, like Holly Golightly, the red-haired, green-eyed beauty had begun life more modestly, the daughter of a groom on the Kentucky estate of Henry J. Schlesinger, who became her first husband. A generation older than Truman’s other swans, she was not generally recognized as a model for Kate McCloud, except by John Richardson, who recalled, “I was convinced it was Mona—it was so obvious.”

Why was Truman so surprised by the reaction of his swans? “I’d never seen anything like it,” Clarke recalls. “I read ‘La Côte Basque’ one summer day in Gloria Vanderbilt’s swimming pool in the Hamptons when Gloria and her husband, Wyatt Cooper, were away. I was reading it while Truman was floating in the pool on a raft. I said, ‘People aren’t going to be happy with this, Truman.’ He said, ‘Nah, they’re too dumb. They won’t know who they are.’ He could not have been more wrong.”

So, why did he do it?

“I wonder whether he wasn’t testing the love of his friends, to see what he could get away with. We had Truman around because he paid for his supper,” Richardson said, “by being the great storyteller in the marketplace of Marrakech. Truman was a brilliant raconteur. We’d say, ‘Oh, do tell us what Mae West was really like,’ or what did he know about Doris Duke? And he’d go on in that inimitable voice for 20 minutes, and it was absolutely marvelous, one story after another. And he loved doing it—he was a show-off.”

Truman bristled at the idea that he was some sort of mascot or lapdog. “I was never that,” he insisted. “I had a lot of rich friends. I don’t particularly like rich people. In fact, I have a kind of contempt for most of them.... Rich people I know would be totally lost … if they didn’t have their money. That’s why … they hang together so closely like a bunch of bees in a beehive, because all they really have is their money.” In what would become a mantra of Truman’s, he often asked, “What did they expect? I’m a writer, and I use everything. Did all those people think I was there just to entertain them?”

“A Slow and Painful Suicide”

Truman’s decline was unstoppable. In addition to his alcohol abuse, he was partaking heavily of cocaine. He fell in love with Studio 54, the quintessential 70s disco, which opened in April of 1977. Truman described it as “the nightclub of the future. It’s very democratic. Boys with boys, girls with girls, girls with boys, blacks and whites, capitalists and Marxists, Chinese and everything else—all one big mix.” He spent many nights watching from the D.J.’s crow’s nest overlooking the dance floor—“the men running around in diapers, cocktail waiters in satin basketball shorts, often lured away by the customers”—or dancing madly by himself, laughing delightedly every time a giant man in the moon suspended over the dance floor brought a spoonful of white powder to its nose. Banished from café society, he embraced this louche, hedonistic world and was taken up by Andy Warhol and the Factory, where drugs flowed as freely as gossip had at La Côte Basque and Quo Vadis. The revelers at Studio 54 didn’t care that Truman had spilled the beans—they didn’t know or care who Babe Paley was.

Bob Colacello, a former editor of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, for which Truman was by this time writing a column called “Conversations with Capote,” felt that “Truman enjoyed it all, but I think that deep down he wished that he could have just gone to lunch with Babe Paley.”

The effect of his new lifestyle was devastating. His weight ballooned, drowning his once delicate features in alcoholic bloat. “Long before Truman died,” John Richardson recalled, “I saw a sort of bag lady with two enormous bags wandering around the corner of Lexington and 73rd, where I lived then. And suddenly, I realized, Christ! It’s Truman! I said, ‘Come on by and have a cup of tea.’” At the apartment, Richardson went to the kitchen to make the tea, and by the time he got back, “half a bottle of vodka—or scotch or whatever it was—was gone. I had to take him outside and gently put him into a cab.”

“I said, ‘People aren’t going to be happy with this, Truman.’ He said, ‘Nah, they’re too dumb. They won’t know who they are.’ He could not have been more wrong.”

Lee Radziwill recalls she and Truman “drifted apart because of his drinking. We just forgot about one another. I mean, I never forgot about him, but we didn’t see each other, because he wasn’t making any sense whatsoever. It was pitiful. Heartbreaking, because there was nothing you could do. He really wanted to kill himself. It was a slow and painful suicide.”

The last straw was when Truman and John O’Shea came to stay with Lee at Turville Grange, her and Prince Radziwill’s country house in England. “They were not getting along well, to say the least. I didn’t want them to come, because I knew, even before he arrived, that Truman was in terrible shape. Stas left me alone with them. I said, ‘You can’t!’ Thank God we had a guesthouse in the courtyard because they were fighting the entire time, and they broke most of the furniture in the cottage. Finally, they left. That’s the last time I remember seeing Truman.”

But what really shattered their friendship was the lawsuit for libel brought against Truman by Gore Vidal. In an interview Truman had given to Playgirl magazine, he related a story about how Vidal “got drunk [and] insulted Jackie’s mother” at a White House dinner party in November 1961 and was bodily removed from the White House by Bobby Kennedy and Arthur Schlesinger. The real incident was more benign—Gore and Bobby Kennedy had indeed gotten into an argument, when Bobby saw Gore’s hand resting on Jackie’s shoulder (“Fuck you”s were allegedly exchanged), but there was no physical heave-ho from the White House. Gore was incensed at Truman’s story, the culmination of a feud that had smoldered between the two men for decades. Vidal demanded an apology and $1 million in damages.

Truman entreated Liz Smith to persuade Vidal to drop his lawsuit, which he refused to do. He then asked her to ask Lee Radziwill to give a deposition in his favor, as he said he had first gotten the story from Lee, but Lee was no longer returning Truman’s calls. So the columnist called Radziwill and asked her to say at least that the incident had in fact occurred, “otherwise, Gore is going to win this lawsuit, and it’s just going to crush Truman.”

Radziwill said, “I knew that Truman loathed Gore. [Vidal] was a very brilliant but very mean man.... When Truman asked me to do the deposition for him, I never knew anything about depositions. I was very upset that he lost. I felt it was my fault.”

The lawsuit lingered for seven years, until Alan Schwartz made a direct appeal to Vidal himself. “Look,” he said. “Truman is in terrible shape between the drugs and alcohol, and you may feel you’ve been libeled, but I’m sure you don’t want to be part of a writer of Truman’s gifts being destroyed.” Gore eventually settled for a written apology.

In July 1978, Truman appeared in an inebriated state on The Stanley Siegel Show, a local morning talk show in New York. Taking note of Truman’s incoherence during the interview, Siegel, the host, asked, “What’s going to happen unless you lick this problem of drugs and alcohol?” Truman, through the fog of his own misery, replied, “The obvious answer is that eventually I’ll kill myself.” The appearance was such a disaster it made headlines: DRUNK & DOPED, CAPOTE VISITS TV TALK SHOW, the New York Post jeered later that day.

Truman had no recollection of what had occurred on The Stanley Siegel Show, but when he read the press accounts he was horrified. He nursed his wounds at a gay disco in SoHo that night, with Liza Minnelli and Steve Rubell, co-owner of Studio 54. The next day, one of his friends, Robert MacBride, a young writer Truman had befriended a few years earlier, removed a gun Truman kept in his apartment and delivered it to Alan Schwartz for safekeeping—a gun that had been given to Truman by Alvin “Al” Dewey Jr., the detective who had been in charge of the Clutter case. Truman was then bundled up and transported to Hazelden, the drug-and-alcohol rehabilitation center in Minnesota, accompanied by C. Z. and Winston Guest—the rare socialites who had remained loyal. Afraid he would back out, they flew with him to the clinic, where he spent the next month. He actually enjoyed his time there, but a few weeks after being discharged, he began drinking heavily again.

Exhausted and unwell, Truman foolishly agreed to a grueling, 30-college lecture tour in the fall of 1978. Gerald Clarke thought he had embarked upon such an ordeal because he needed to know that he was “still loved and admired,” but the tour, too, was a disaster. He became so incoherent in Bozeman, Montana, that he had to be escorted offstage. Back on Long Island, Truman continued to slide. “I watch him when he’s sleeping,” observed Jack Dunphy, Truman’s former partner and friend of more than 30 years, “and he looks tired, very, very tired. It’s as if he’s at a long party and wants to say good-bye—but he can’t.”

Users and Hustlers

“I did stop working on Answered Prayers in September 1977,” Truman wrote in the preface to his 1980 story collection, Music for Chameleons. “The halt happened because I was in a helluva lot of trouble: I was suffering a creative crisis and a personal one at the same time.” That personal crisis was John O’Shea.

O’Shea seemed an unlikely partner for Truman—married for 20 years, with four children—but he was “just the kind of man Truman liked,” said Joe Petrocik, “a married, Irish, Catholic family man.” O’Shea was an aspiring writer, and he loved the life Truman introduced him to, and the possibility that he, too, could have a viable writing career. But he lacked Truman’s talent, charm, brilliance, and drive. “He was so ordinary that it was breathtaking,” Carol Matthau told George Plimpton for his oral history of Capote, but she also felt that the relationship had “hastened Truman’s death.” Perhaps Truman was trying to capture his early childhood memories of his biological father, Arch Persons, a rascally, stout businessman and something of a con man. Curiously, O’Shea’s wife and children adored Truman and didn’t seem to resent the role he played in breaking up their family. Such was Truman’s charm.

But if the arrangement suited Truman psychologically—and sexually—it had become disastrous, even dangerous. In late 1976, Truman was locked in a nasty battle with O’Shea, exacerbated when O’Shea became involved with a woman. Claiming that O’Shea had run off with the manuscript of the “Severe Insult to the Brain” chapter of Answered Prayers, he sued his former lover in Los Angeles Superior Court, eventually dropping the suit in 1981. The two men reconciled, then broke up, again and again. In an attempt at revenge, Truman hired an acquaintance to follow O’Shea and to rough him up. Instead, the person ended up setting O’Shea’s car on fire.

Truman’s decline is usually blamed on the debacle caused by “La Côte Basque 1965,” but Gerald Clarke believes the seeds of his self-destruction were planted much earlier, when he was researching In Cold Blood. He’d gotten close to Perry Smith during those five long years of visiting him in a bleak Kansas prison and then waiting for him to be executed. In some ways, the two men were alike: short, compactly built, artistic, the products of deprived early childhoods—it would have been easy for Truman to look into Perry Smith’s black eyes and think he was looking at his darker twin. “There was a psychological connection between the two of them,” Clarke believes. “Perry’s death took it out of him.” But Truman knew that the value of In Cold Blood “required the execution to take place.” He couldn’t finish his book otherwise. “He wrote that he wanted them to die—that started the decline.”

He wasn’t prepared for the effect of watching Smith’s execution by hanging. The man swung for more than 10 minutes before he was pronounced dead. After leaving the prison, Truman had to pull his car over to the side of the road, where he wept for two hours. It’s possible that those events set the stage for the vitriol of Answered Prayers, originally conceived by Truman to be “a beautiful book with a happy ending”; instead it became a kind of j’accuse of the rich and socially prominent, revealing, if not reveling in, their treachery, deceit, vanity, and murderous impulses. Under their polished veneers, they are all users and hustlers, like P. B. Jones.

The revelers at Studio 54 didn’t care that Truman had spilled the beans—they didn’t know or care who Babe Paley was.

It was to his dear friend Joanne Carson that Truman turned when he was in desperate straits, sick and exhausted, buying a one-way plane ticket to Los Angeles on August 23, 1984. Two days later, Joanne entered the guest bedroom to find Truman struggling for breath, his pulse alarmingly weak. She said that Truman spoke of his mother and then uttered the phrases “Beautiful Babe” and “Answered Prayers.” Against his wishes, she called the paramedics, but by the time they arrived Truman was dead.

As for what happened to the rest of the manuscript, no one really knows. If it was stowed away in a Greyhound bus depot, possibly in Nebraska, where he had stopped during his 1978 college tour, as Joe Petrocik believes, or in a safe-deposit box somewhere, as Joanne Carson believed, it has never surfaced. Alan Schwartz says that O’Shea “claimed Truman had written the book, claimed he had stashed it away, but we never found a clue that he did.” Another theory is that Truman destroyed it himself, realizing, perhaps, that it didn’t come up to his Proustian standard. Jack Dunphy, who died in 1992, believed that, after the publication of “Kate McCloud,” in 1976, Truman never wrote another line of the book.

Gerald Clarke wrote in his biography, “All that the world will ever see of Truman’s magnum opus is the one hundred and eighty pages that Random House published in 1987.... Like other unfinished novels—Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood, for example, or Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon—the abbreviated Answered Prayers [consisting of “Unspoiled Monsters,” “Kate McCloud,” and “La Côte Basque”] is tantalizingly incomplete. Yet, like them, it is substantial enough to be read, enjoyed and, to a limited degree, judged on its own merits.” Clarke believes that Truman simply abandoned the novel.

As for Truman’s posthumous reputation, John Richardson said, “I think that the gossipy part will fall away, and he’ll be remembered as a very brilliant writer who, like so many other writers, died of drink. He joins a tradition. His name—it’s such an unforgettable name—will be remembered.”

Truman was “a giant talent, but after so much fame and fortune, he slid downhill,” recalls Liz Smith. “He had loved all those beautiful women so much, but they never returned his love. I still miss him. New York doesn’t seem to have epic characters like Truman Capote anymore. There are no major writers today that matter in the way that he mattered.”

Louise Grunwald agrees. “There’s no one like him anymore, not that there ever was anyone like him. Just as there are no places like La Côte Basque. It’s all changed. Truman wouldn’t recognize New York anymore. It’s ghostly.”

There was a memory that Truman liked to relate, about a husky boy from his childhood in Monroeville, Alabama, who spent an entire summer digging a hole in his backyard. “Why’re you doing that?,” Truman had asked. “To get to China. See, the other side of this hole, that’s China.” Truman would later write, “Well, he never got to China; and maybe I’ll never finish Answered Prayers; but I keep on digging! All the best, T.C.”

Sam Kashner is a Writer at Large at AIR MAIL. Previously a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, he is the author or co-author of several books, including Sinatraland: A Novel, When I Was Cool: My Life at the Jack Kerouac School, and Life Isn’t Everything: Mike Nichols, as Remembered by 150 of His Closest Friends