“Life is a masquerade, old chum” could serve as the motto for Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City, a guided tour through the forgotten byways and fabulous lore of cross-dressing and gender-bending. The book couldn’t arrive at a more critical juncture, as neo-Puritan scourges target Drag Queen Story Hour and inclusive bathrooms as threats to our once fertile nation.

Its author, the effervescent Elyssa Maxx Goodman (who also goes by the handle “Miss Manhattan”), is best known around the beehive as the host of a monthly nonfiction reading series in the East Village which has attracted a loyal audience of literate hotties since 2014. She is also a widely published journalist and photographer. But this book, her first, represents her overriding longtime pash.

Goodman’s enthusiasm for drag and all of its fixings began when she and her family used to visit Lips, a drag restaurant in Fort Lauderdale whose roster included “the inimitable Twat LaRouge, who performed in a wig and body formed entirely from painted Styrofoam swirls.” As the saying goes on the prairie, once you’ve seen Twat LaRouge, there’s no circling back, and Goodman became an avid student of the art and its ethos. “The outlook of drag,” she writes, “the triumph of glamor over negativity, would become the driving force of my own life.”

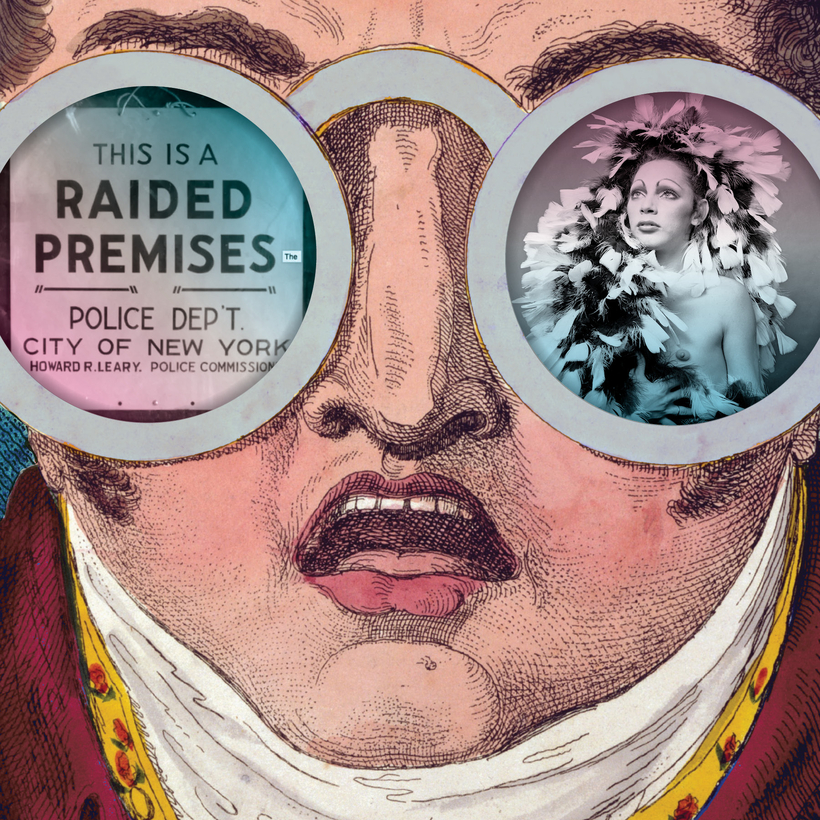

In these pages Goodman details and salutes New York City’s drag history in all of its tatterdemalion glory, from the “Pansy Craze” of the 1920s to the Harlem ball scene to the dive-bar back rooms to the Broadway stage to, well, wherever false eyelashes moth by night. Glitter and Concrete’s approach may be chronological, but its effect is kaleidoscopic. Its real-life cast of divas and princes evolves into an extended family.

As the saying goes on the prairie, once you’ve seen Twat LaRouge, there’s no circling back.

My own first exposure to drag personalities was a segment of The David Susskind Show devoted to Andy Warhol’s “superstars.” It was a revelation. Teenage me was agog. Life in suburban Maryland had not prepped me for this.

One of the grousing superstars was Jackie Curtis, who, as Goodman writes, made no effort at plausibly passing as a woman, preferring to look like the original hot mess—“haphazard makeup, chaotic eyelashes and wigs.” Along with the incandescent Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn, Curtis would become part of Warhol’s repertory company of high-strung chatterboxes that presented drag not as Milton Berle burlesque but as a way of life, a bickering, low-rent, hyper-real domesticity.

“The outlook of drag, the triumph of glamor over negativity, would become the driving force of my own life.”

An even more dramatic eye-opener for the uninitiated was the cinéma-vérité documentary The Queen (1968), about a drag beauty pageant held at Town Hall that climaxed with a scathing monologue by Crystal LaBeija, whose battle cry, “I have a right to show my color, darling!,” would prove prophetic. For on June 28, 1969, came the clatter of high heels and the shattering of glass heard round the world—the riot at the Stonewall Inn.

The Stonewall was a Mob-owned gay bar in the West Village that was regularly raided by the police (part of the price of doing business), but this time the cops reportedly roughed up a lesbian in male drag as they were loading her into the wagon, and all rumbling hell broke loose. Goodman cites the historian Martin Duberman, who wrote, “Police found themselves face to face with their worst nightmare: a chorus line of mocking queens kicking their heels in the air Rockettes-style.” This wasn’t something they trained you for at the police academy. Pent-up fury had been uncorked. “Drag, specifically worn by people of color, was the riot’s beating heart,” Goodman writes.

Drag queens of color at the center of the fray and the struggle would become a source of friction and conflict post-Stonewall. Some mainstream feminists decried drag culture as misogynist and regressive—a harpy caricature of womanhood—while “some gay men,” Goodman writes, “embraced a hypermasculinized aesthetic, like a living Tom of Finland drawing.”

Yet there were occasions when the twain met. The drag performer Ruby Rims was hired as a joke at the Anvil, the stage still so slick with Crisco that she was afraid she’d slide right off. It had the makings of a scene from William Friedkin’s Cruising played for slapstick, but Rims troupered on and became a house act, singing “O Holy Night” on Christmas Eve to a rapt, burly audience.

My own first exposure to drag personalities was a segment of The David Susskind Show devoted to Andy Warhol’s “superstars.” It was a revelation. Teenage me was agog. Life in suburban Maryland had not prepped me for this.

Along with its flotilla of high-definition individuals (from International Chrysis to drag king Wang Newton), Glitter and Concrete shows how the fever chart of drag’s popularity and creative energy has always fluctuated in sync with New York City’s fortunes, but with spikier ups and downs. (Everything hits marginalized communities harder.)

The AIDS epidemic, the repressive crackdown on nightlife under the Rudy Giuliani mayoralty (which resulted in the closing of “Sally’s II, Edelweiss, and other venues where trans showgirls and sex workers of color thrived”), the thundershock of 9/11, the triumphant return of Wigstock in 2018 after a 17-year hiatus, the stultifying malaise and toll of the coronavirus pandemic—through all this and more, the drag community managed to roll with the punches and gain national acceptance and familiarity.

Laverne Cox became the first transgender person to appear on the cover of Time, RuPaul’s Drag Race began its powerhouse run on cable, and Kinky Boots was revived Off Broadway, the opening line of the New York Times review cheering, “You can’t keep a drag queen down, at least not for long.”

In a just world, Glitter and Concrete would be able to swing out on a similar celebratory upbeat note, but in this country joyousness has to keep looking over its shoulder. The forces of reaction never stop grinding their teeth in their sleep, and the last two years have witnessed a vicious vibe shift against drag performers and transgender people in the political sphere.

This “translash” has been stoked by alt-right influencers, polemicists, and libertarian tech bros (along with the usual droop squad of centrist pundits), conducted on social media where the slur “groomer” is pervasive, waged at street level by militant incels and MAGA intimidators such as the Proud Boys, and taken up by Red State legislators looking for easy targets to stigmatize and vilify.

Signing the cringingly titled “Let Kids Be Kids” bill, a comprehensive anti-drag, anti-trans clampdown package, Florida governor and flop-sweat presidential candidate Ron DeSantis proclaimed, “As the world goes mad, Florida represents a refuge of sanity and a citadel of normalcy.”

To which a wise adage from the illustrious drag queen Flawless Sabrina provides the perfect retort: “Normal is a setting on the dryer.” Listen to mama and leave everybody be.

Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City, by Elyssa Maxx Goodman, will be published by Hanover Square Press on September 12

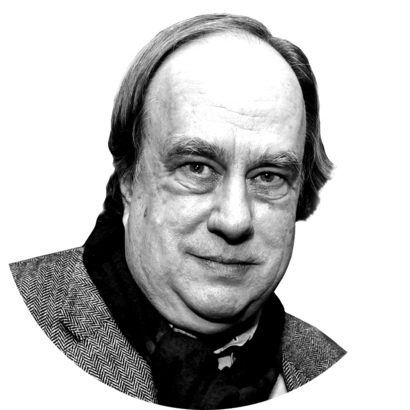

James Wolcott is a Columnist at AIR MAIL. He is the author of several books, including the memoir Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty in Seventies New York and Critical Mass, a collection of his essays and reviews