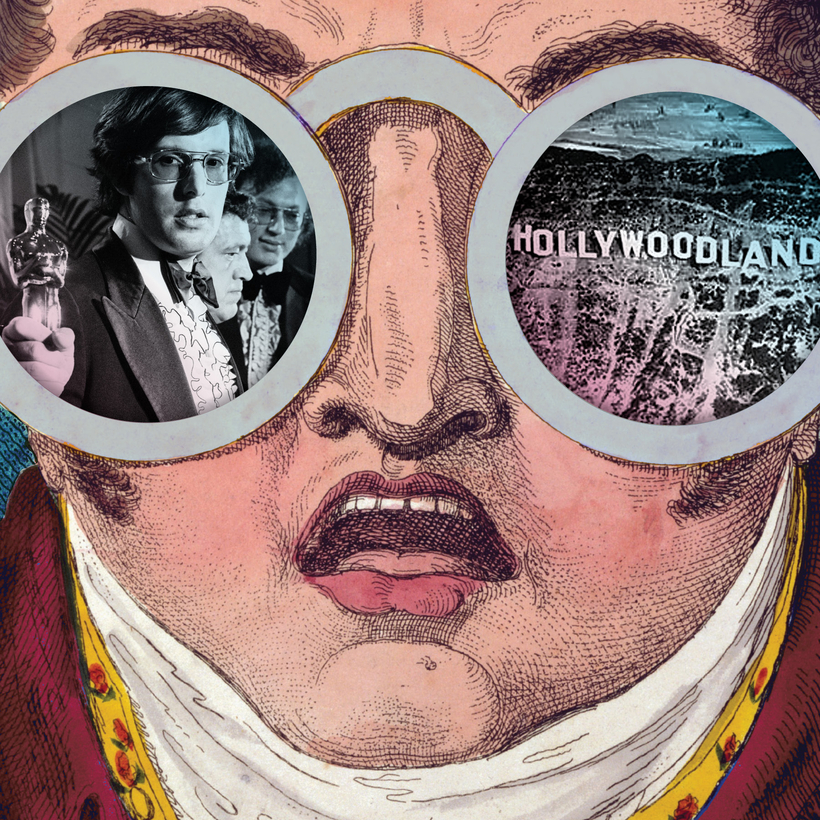

The HOLLYWOOD sign, back when it read HOLLYWOODLAND, used to be illuminated by 4,000 lights. That was a century ago. By the 1970s, the lights were in an almost constant cycle of disrepair and half-hearted renovation. Why they were never fully replaced goes a long way toward explaining the short-term memory of so many people who work in the movie business. You could reasonably argue that the disappearance of those lights mirrored the long march of the loss of the great talents and characters that made the movie business so enticing to the rest of the world.

I have a suggestion. Why not, starting now, begin the process of returning those lights to the sign, with each one representing one of the human lights of the town that has flickered out. I would begin with William Friedkin, who died this week at the age of 87. He had spent a few days in the hospital, returned home to the house he shared with Sherry Lansing, his wife of more than three decades, and died in his sleep.