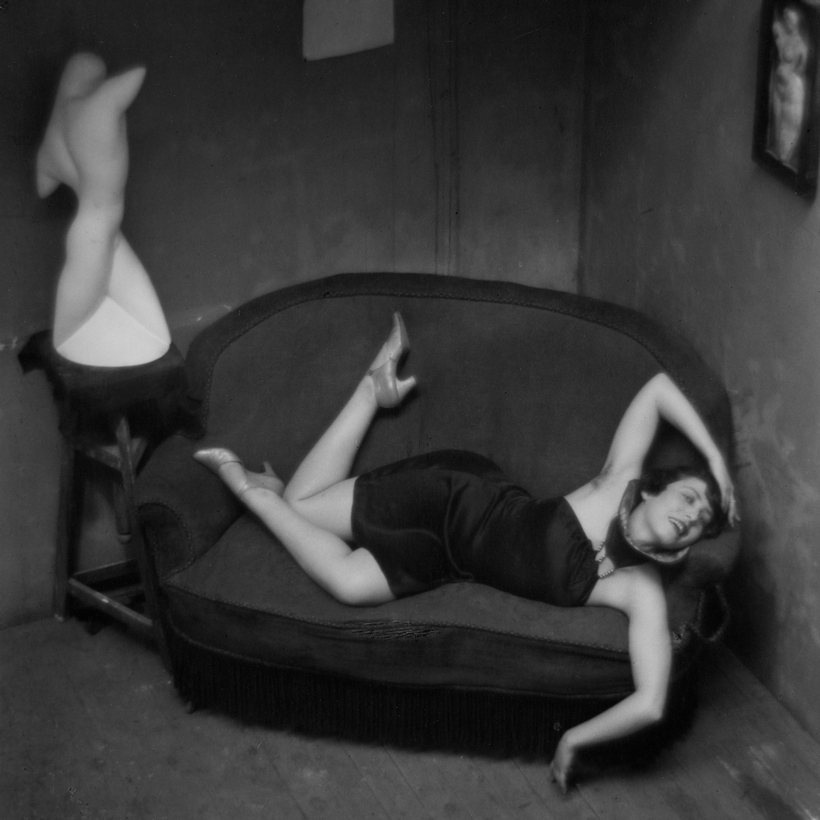

Though André Kertész is now recognized as one of the seminal photographers of the 20th century, for many years he languished in obscurity. First in his native Hungary, then in Paris, where he lived from 1925 to 1936, Kertész emerged as a pioneer of a new kind of photography—lyrical, but fortified by a peerless sense of composition. In America, where he spent the remainder of his life, recognition came late. For decades he was forced into uninspiring commercial work. In 1957, he told his friend the Hungarian-French photographer Brassaï, “I am dead. You are looking at a dead man.”

Not quite. As Patricia Albers recounts in Everything Is Photograph—the first full-length biography of Kertész—he would turn out to be a rare thing: a “dead” artist who lived to witness his own resurrection.