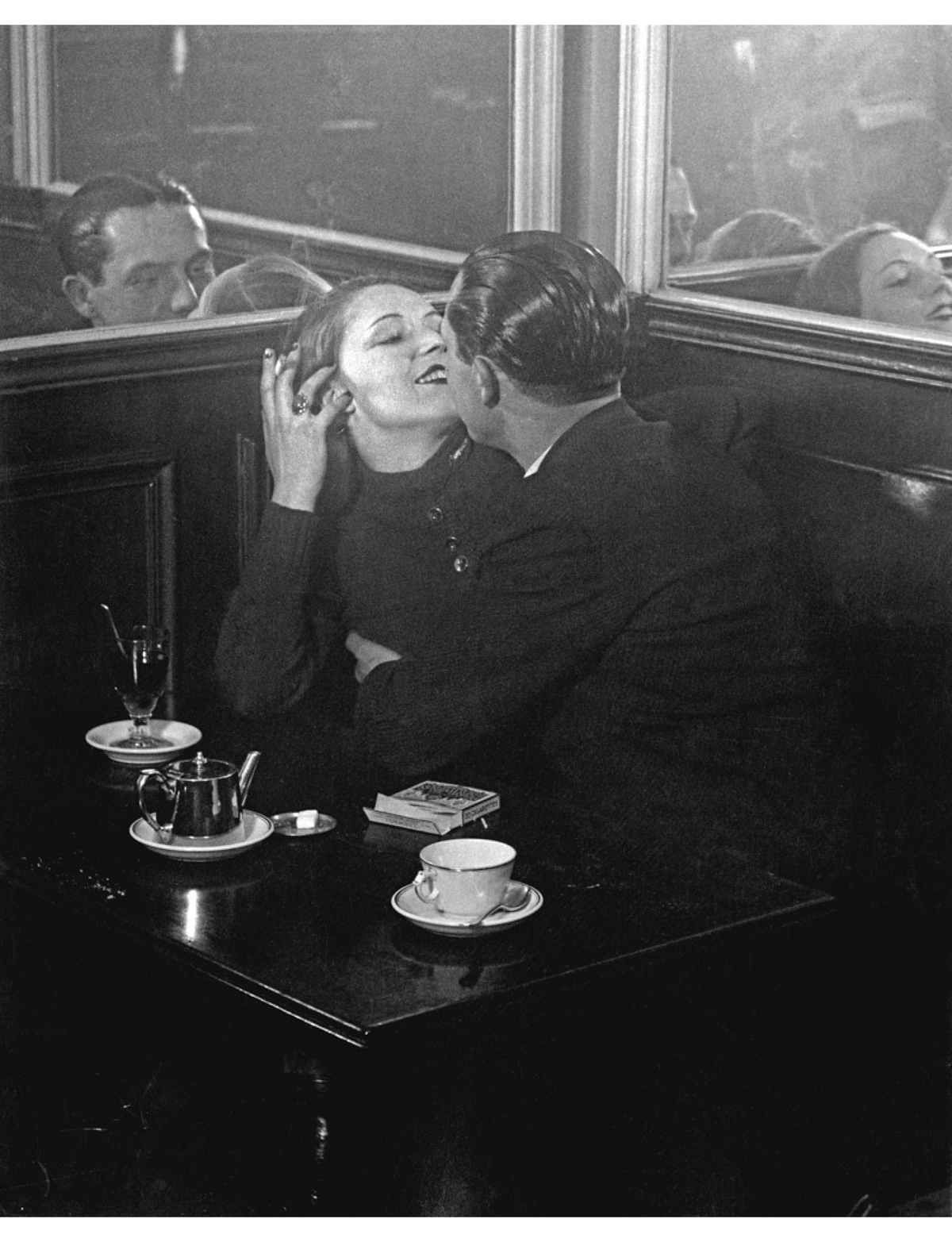

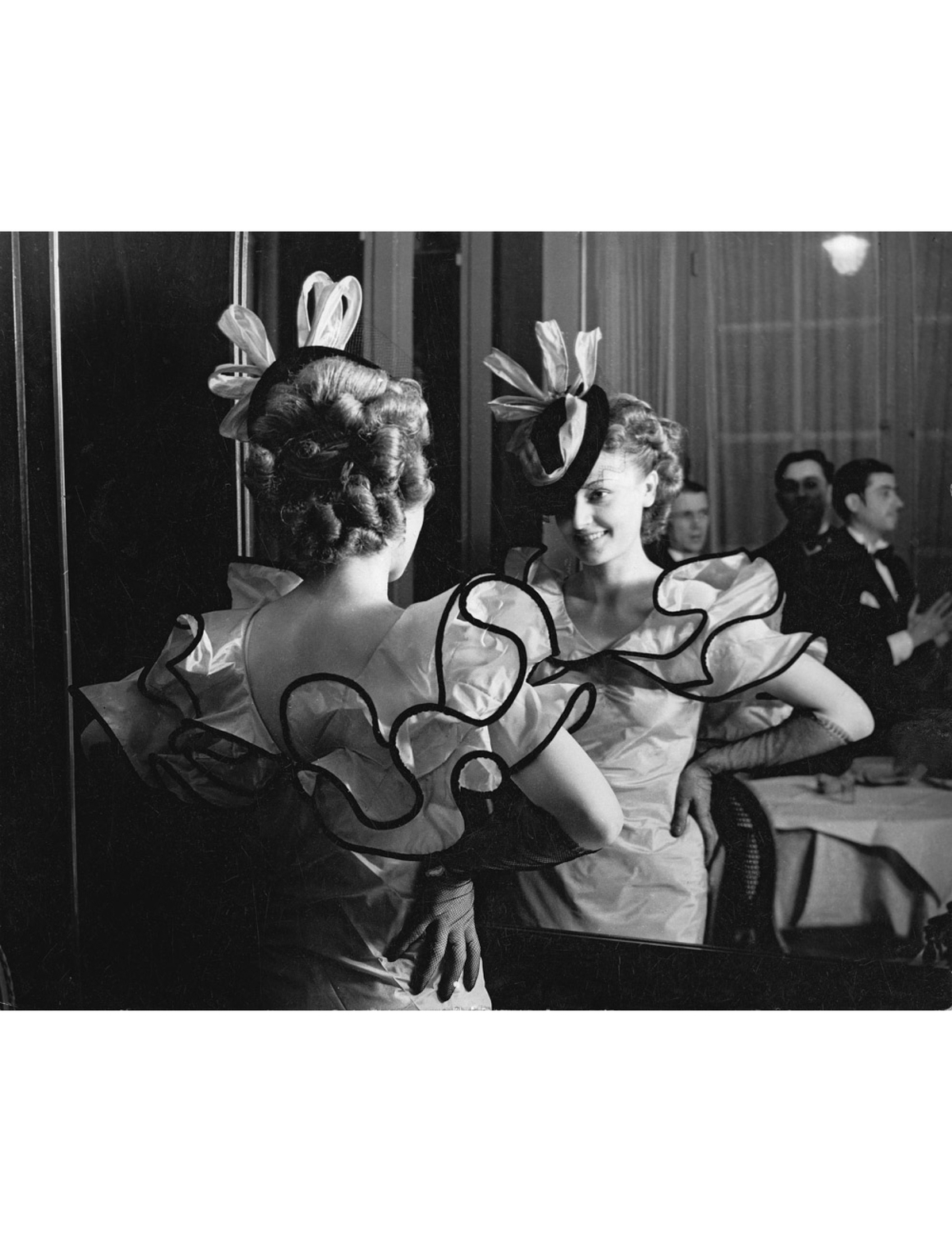

The photographer Brassaï was many things. Hungarian by birth, Parisian by choice. “A living eye,” according to Henry Miller. A stage designer, sculptor, filmmaker, writer. A chronicler of 20th-century high society and of prostitutes. An avid admirer of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s. His real name was Gyula Halász, and the city of Paris—its bâtiments and boulevards—was his specialty.

Brassaï was born in Brassó, present-day Romania, on September 9, 1899, at nine o’clock at night. He considered the number nine to be a symbol of cosmic order—a sign, he believed, that he was destined for greatness. In 1903, when Gyula was four, his family spent a year in Paris. He settled there for good in February 1924.