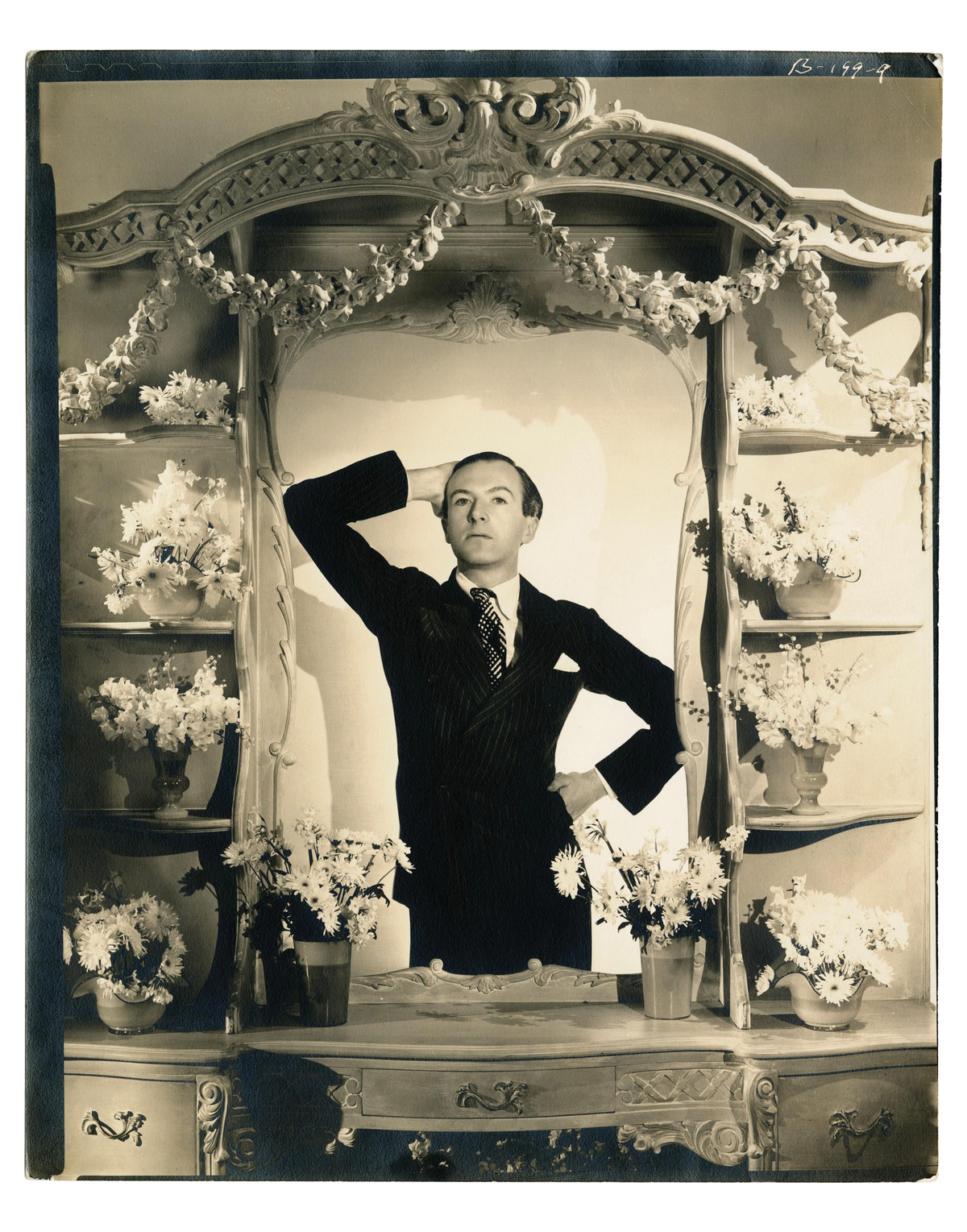

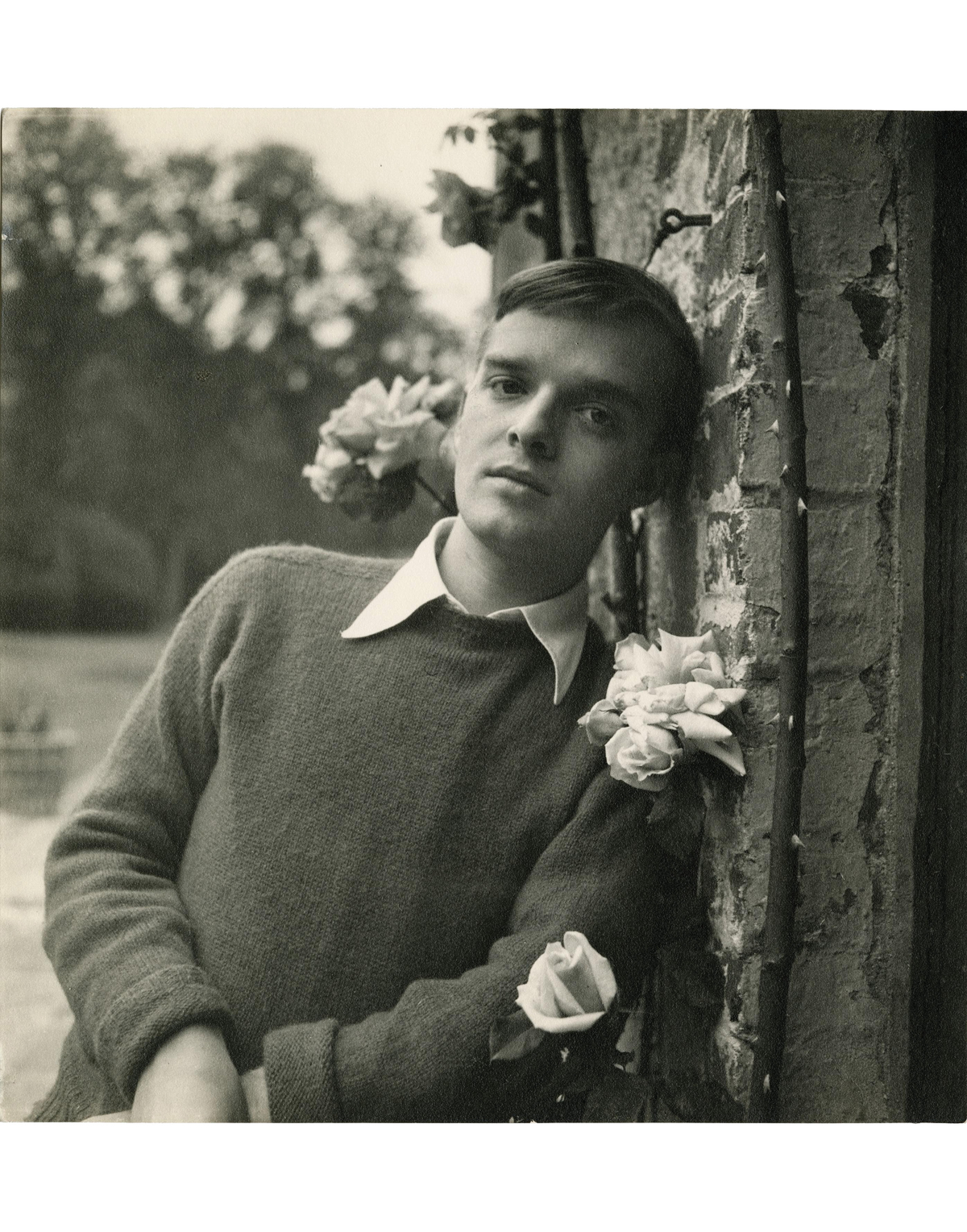

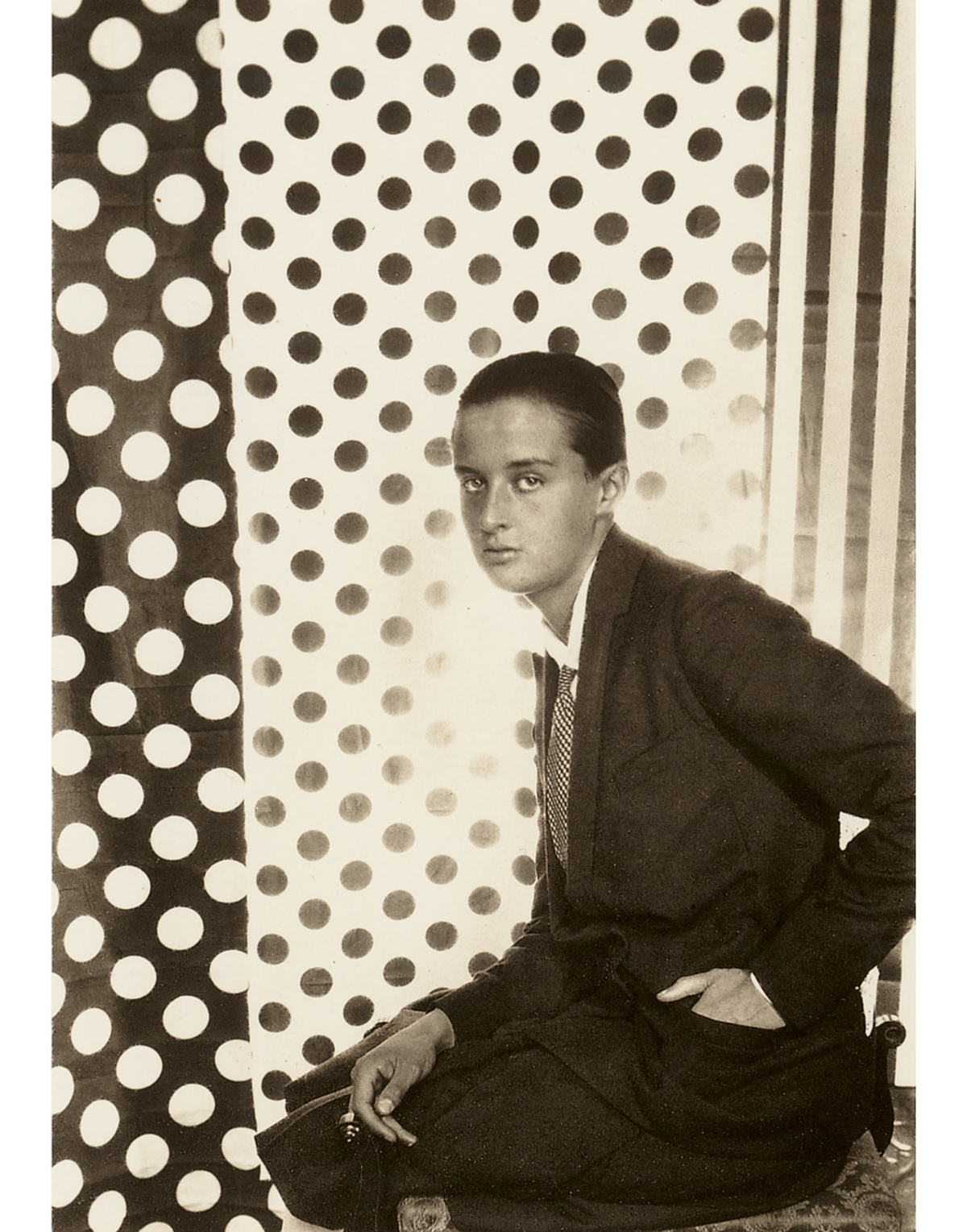

Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton, born in 1904 in Hampstead, England, looked at the world and thought he could do better. “I have wonderful plans and I am going to do marvelous things,” announced the youngster. Taught how to use a camera by his nanny, educated at Harrow and Cambridge, he worked briefly in the family timber business and then proceeded to build a Beatonian brand: life as a rococo fantasy where he would craft the sets and costumes, write the essays and plays, and capture it all through his camera lens in a photographic style that married Edwardian stage portraiture and European Surrealism. With no use for the quotidian, Beaton’s visual sleight of hand turned balloons, cellophane, mirrors, paper, and vases into fantastical dreamscapes and silvery grottos, his patient sisters sitting for pictures until society came to call.

In 1927, when Beaton was just 23, his work captured the attention of Vogue’s Edna Woolman Chase, who invited him to become a contributor. That same year, Beaton’s first exhibition of photographs attracted the cream of London society, and the self-taught savant was accepted as an incandescent member of Britain’s Bright Young Things. Now open at London’s National Portrait Gallery, the exhibition “Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World” surveys the groundbreaking oeuvre of one of the 20th century’s most influential artists. More than 250 items—including photographs, letters, sketches, and costumes—showcase Beaton at his most triumphant.

Vogue and Beaton would remain inextricably linked for a quarter of a century. He was the magazine’s star contributor, indispensable not only as a photographer and fashion illustrator but as an arbiter of taste, a man in the know. In 1929, Beaton was dispatched to Hollywood to capture portraits for Vogue’s sister publication Vanity Fair. He was smitten. “Apollos and Venuses everywhere,” he exclaimed—Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn, Joan Crawford, and, later, Marlon Brando, Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe. Everyone of consequence arranged themselves before Beaton’s lens.

Hollywood recognized what Vogue had in Beaton—a talent of singular breadth. Reward came in the form of stunning commissions. He would design the Belle Époque sets and costumes for Vincente Minnelli’s Gigi (1958), which brought him his first Academy Award. Two more Oscars, for art direction and costume design, followed, bestowed for his splendid work on George Cukor’s My Fair Lady (1964).

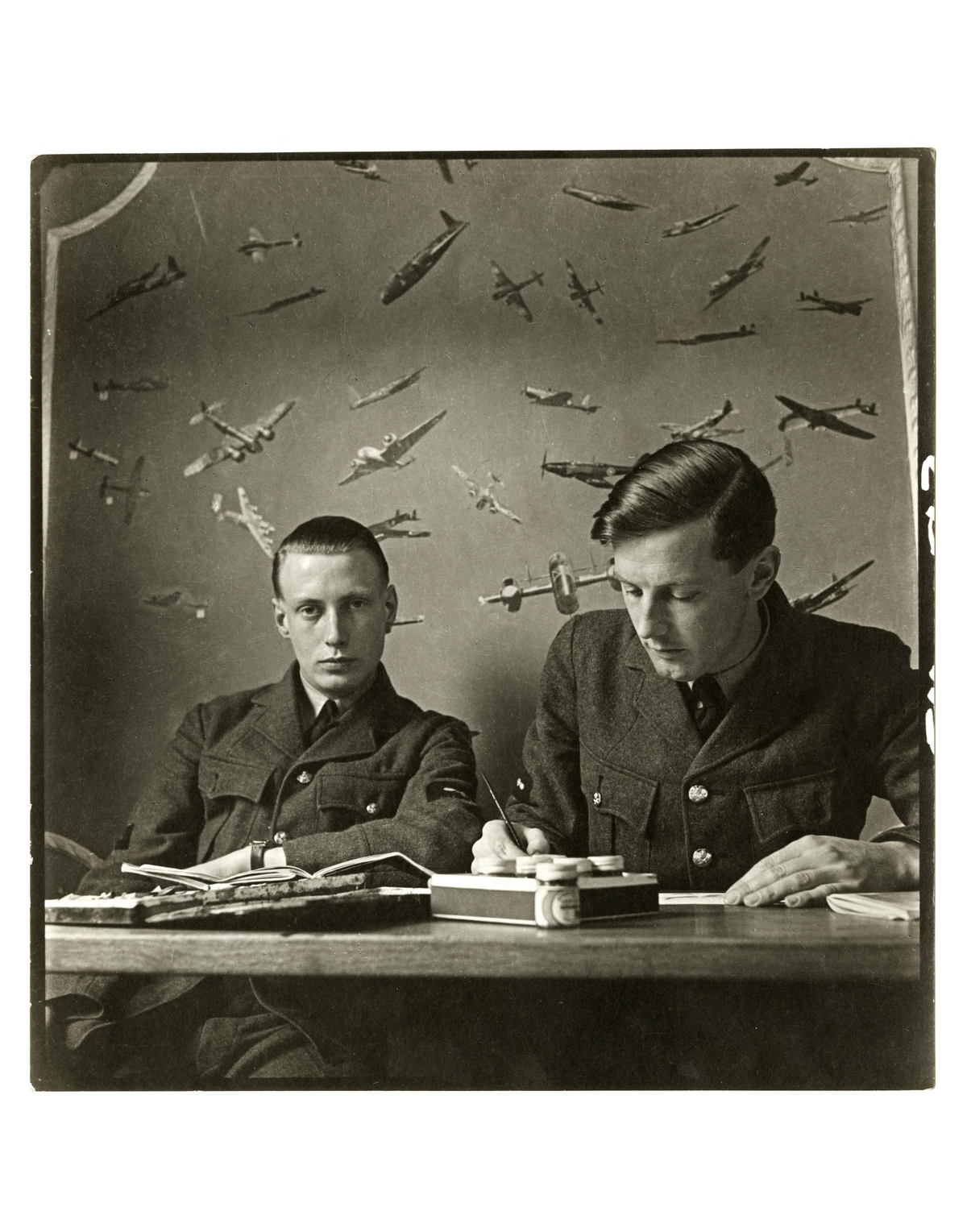

As the 1930s were ending and a second World War approached, Beaton’s shimmering visions and decorative flourishes began to date. Images from a new breed of photographers were more realistic, kinetic, existentialist. Yet in July 1939, an invitation from Buckingham Palace to photograph Queen Elizabeth, the wife of King George VI, took Beaton’s career in an unanticipated direction. His highly romanticized aesthetic resulted in powerful pictures of a monarchy in motion. Beaton’s fairy-tale association with the royal family would span decades, and for his service to the Crown he was knighted. By 1979, however, and just a year before his death, he was back in style at 75, commissioned to shoot the Paris collections for French Vogue.

“Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World” is on at the National Portrait Gallery in London until January 11, 2026

Tracy Doyle is a New York–based creative director who has worked with brands such as Tom Ford, Chanel, Gucci, Tiffany & Co., and Max Mara. Previously, she was a photo editor at Life and Interview magazines