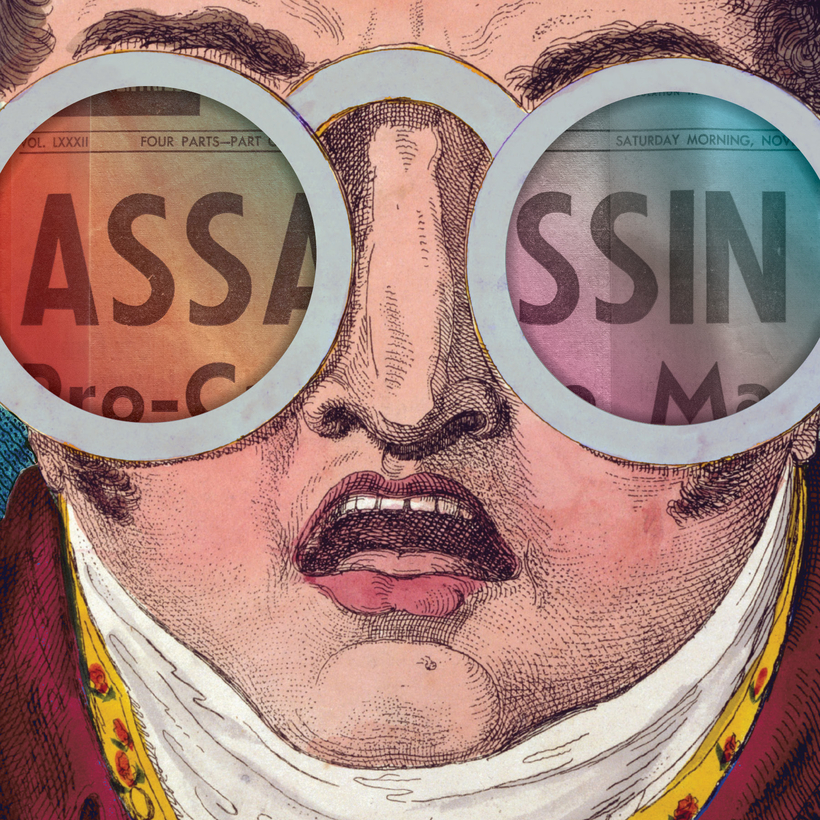

Who is Ryan Routh, the man arrested on Sunday after apparently attempting to assassinate Donald Trump on a Florida golf course? No sooner had his name been released to the public than theories began to percolate on social media. “What are the odds that this shooter, who spent months fighting in Ukraine, has zero links to anyone in US military or intelligence circles? Find them,” Charlie Kirk, of the right-wing group Turning Point USA, demanded on X. Similarly, Laura Loomer posted, “Ryan Routh served in the US foreign legion in Ukraine, which is reportedly tied to the CIA.”

Others theorized that Routh was connected to BlackRock, the asset-management giant. In a post that has been viewed more than three million times, X user “Concerned Citizen” claimed that Routh had appeared in a BlackRock commercial, just like Thomas Crooks, who was killed while trying to assassinate Trump in July.

After that earlier attempt, some conspiracy theorists concluded that the Secret Service deliberately allowed Crooks to get within shooting range of Trump. Former first lady Melania Trump, who rarely comments on current events, said, “There is definitely more to this story. And we need to uncover the truth.” Others argued that Crooks was set up to take the blame for a fake assassination attempt designed to earn sympathy for the former president and current Republican candidate.

All of these claims were quickly disproved (that is, unless the mainstream media is in on the conspiracy). Routh did go to Ukraine hoping to enlist in the war against Russia, but he came back disappointed; no military unit wanted anything to do with a 58-year-old suffering “delusions of grandeur.” Proponents of the idea that Crooks’s attempt was staged have difficulty explaining the fact that bullets from his gun killed one person in Trump’s audience and wounded two others. Crooks did happen to appear in the background of a 2022 BlackRock commercial aimed at teachers that was filmed at his high school, but he had no link to the company itself. Routh was never in a BlackRock ad.

Still, the two would-be assassins did have something important in common, not just with one another but with most of the people who have ever tried to kill an American president. They were marginal, friendless, and powerless figures—in a word, losers. And that is exactly why they became the focus of such elaborate conspiracy theories.

There is something instinctively unacceptable, not just morally but imaginatively, about the idea that someone without any of the usual markers of importance—authority, status, wealth, fame—could become, with a single act, the most consequential person in the world. It violates our sense of narrative, the stories we tell about the way the world works.

After all, it would be hard to imagine a greater contrast than the one between Trump—long one of the richest and most famous people in America, and since 2016 one of the most powerful—and the men who tried to kill him. Routh, who supported himself by building storage sheds in Hawaii, had a long criminal record, including a felony weapons conviction. A North Carolina police officer who arrested him in 2002 recalled that he “acted like he had some sort of mental health issues.” Crooks, 20 years old, was remembered by high-school classmates as a “loner” and “weirdo” who was often bullied.

They were marginal, friendless, and powerless figures—in a word, losers. And that is exactly why they became the focus of such elaborate conspiracy theories.

When it comes to presidential assassins, this is a familiar tale. Lee Harvey Oswald is the best-known example. In his short life—he was just 24 when he shot John F. Kennedy—Oswald enlisted in the Marines only to be court-martialed twice and demoted from private first-class back to private. He defected to the U.S.S.R. hoping to be honored as a political symbol, but soon grew tired of working in a factory and came back to the U.S. He had no stable job—he had been working at the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas for just a month when he shot Kennedy from the building’s sixth floor—and no close friends. His wife, Marina, lived in fear of his abuse.

Long-ago and little-remembered assassins tend to follow the same pattern. Leon Czolgosz, who killed William McKinley in 1901, was an unemployed manual laborer who lived as a recluse on his family’s farm; a few months before the assassination he tried to join an anarchist organization called the Liberty Club, but its members turned him away. Charles Guiteau was destitute and homeless when he killed James Garfield in 1881, blaming the new president for his failure to obtain a civil-service job. Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, who tried to shoot Gerald Ford in 1975, was a follower of Charles Manson who carved an X into her forehead as a sign of loyalty. (Perhaps only John Wilkes Booth, a celebrated actor, defies the general rule.)

When people like these can change the course of history, or literally come within an inch of changing it, it becomes terrifyingly clear that the governments, corporations, and even spy agencies tasked with managing the world are actually just struggling to keep up. The reason why the Kennedy assassination dealt such a staggering blow to American confidence is that, at the height of the Cold War, the very survival of humanity depended on the ability of those authorities to keep violence and madness from spiraling out of control. If a pathetic figure such as Oswald could kill a president as charismatic and youthful as Kennedy, anything could happen—and for the rest of the 60s it did. In a strange way, it’s more reassuring to believe that the deep state or the C.I.A. is behind the assassination of a president; at least they are supposed to be powerful.

For the shooters themselves, it is precisely the chance to rewrite the narrative—their own and the world’s—that makes the act so appealing. Most have a political justification for their actions: Czolgosz was an anarchist, Oswald was pro-Castro, Fromme claimed she was acting in defense of California’s redwood trees, and Ryan Routh seems to have been radicalized by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. (His failed mission to Ukraine was in some ways a 21st-century version of Oswald’s unrequited flirtation with the Soviets and Cubans.)

But politics is just the most available route to what an assassin really wants: to be recognized, finally, as the important person he always knew he was. “I would tremendously enjoy the invitation to join any monumental worthy cause to bring about real change in our world,” Routh once wrote on his LinkedIn profile. Instead, like so many assassins and would-be assassins before him, he found a monumentally unworthy one.

Adam Kirsch, an editor at The Wall Street Journal’s weekend Review section, is the author of several books, including On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice