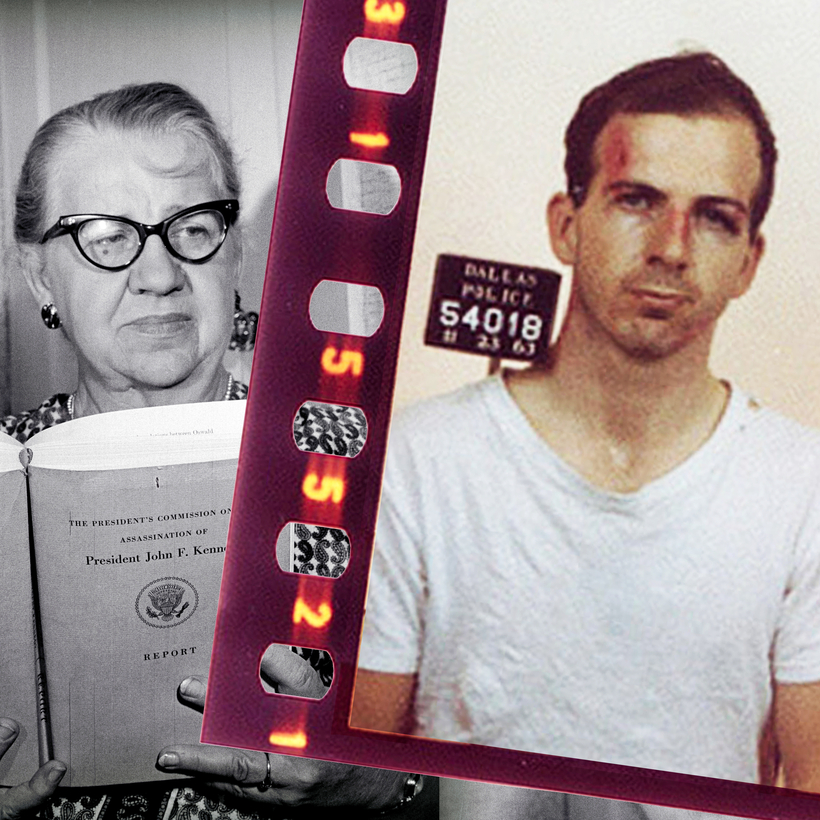

American Confidential: Uncovering the Bizarre Story of Lee Harvey Oswald and his Mother by Deanne Stillman

In mid-February 1964, 56-year-old Marguerite Oswald, of Fort Worth, Texas, arrived in Washington to testify before the Warren Commission. She was there to talk about her late son, Lee, known around the world as the man who had killed John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and who, two days later, had himself been murdered by Jack Ruby in the basement of Dallas Police headquarters.

Marguerite had been a ubiquitous character in the media since the day of Kennedy’s assassination, when she’d called up the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, identifying herself as Oswald’s mother and demanding a ride to Dallas.