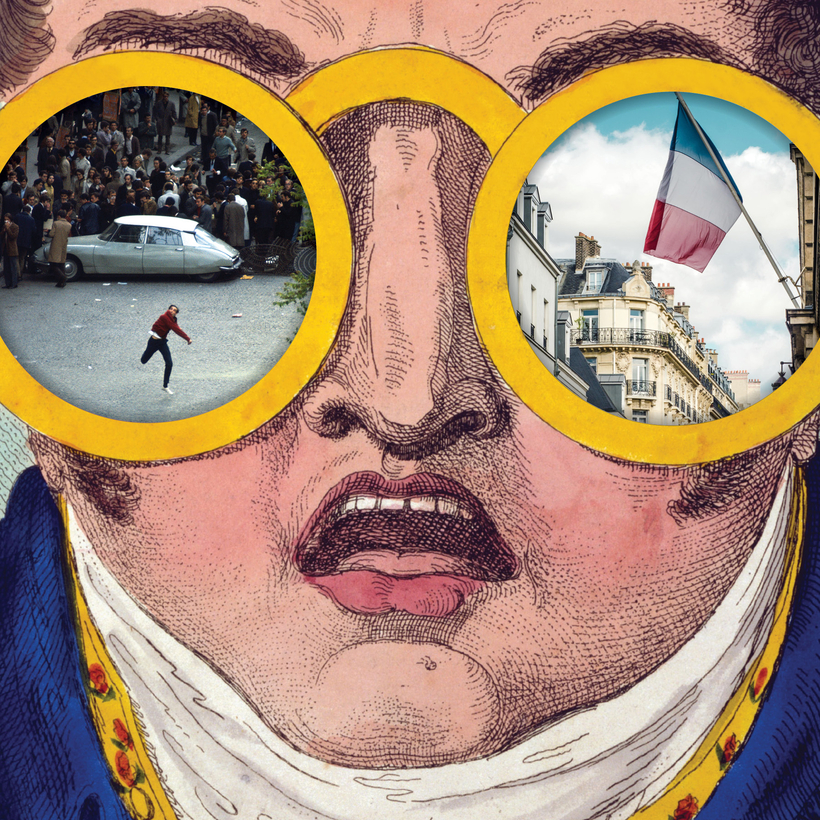

May, the month of the Cannes Film Festival and the French Open, is when France usually pivots, turning heel on a season of gloom and rain to show off its finery and raison d’être.

May is also the month the French, who make striking something of a national sport, get their protest mojo back, and this year is no exception. On May 14, there was a strike among sanitation workers. On May 16, firefighters followed suit. On May 21, employees of the national railway, S.N.C.F., took to the streets demanding a pay raise during the Olympic Games. And on May 23, staffers at Radio France said they, too, had had enough and refused to be merged with—can you imagine?—French public television.