Washington politics have long been compared to high school, but they’ve got nothing on France right now.

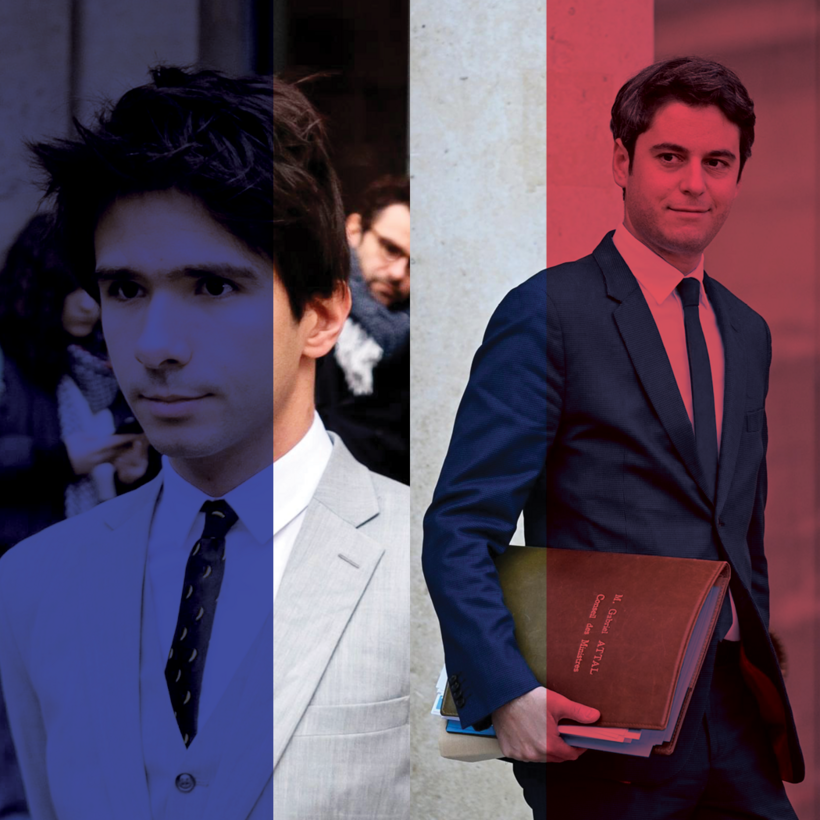

This is not a reference to the tender age, just 34, of France’s youngest-ever prime minister, Gabriel Attal, appointed just after the new year. It’s more literal than that. Among the haters that Attal’s shock appointment brought out, inside and out of President Emmanuel Macron’s camp, none is more voluble, nor more personally dedicated, nor more relentless, than the “anti-system” lawyer and pamphleteer Juan Branco. He also happens to have been Attal’s private-school classmate.