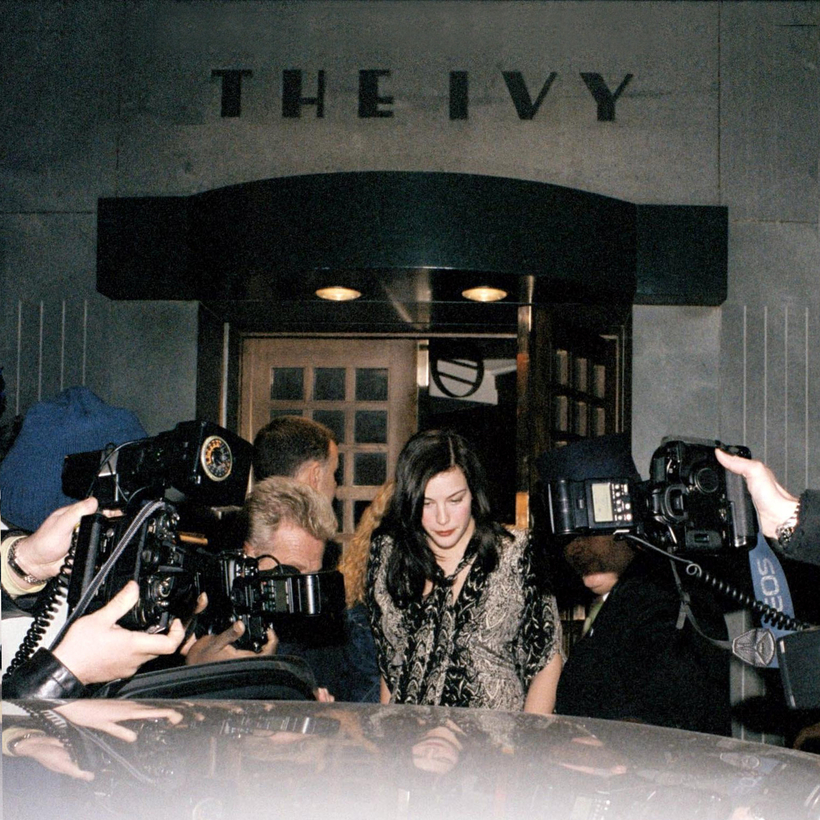

At first glance, “Ivy” is not an ideal name for a restaurant. Ivy is impossible to kill. Rapidly expanding. Occasionally poisonous. But the Ivy has grown into at least part of its name. From a single site on the corner of West Street in Covent Garden, there are now dozens of spin-off brasseries and cafés and “Ivy Asias”—Asian-themed variants—up and down the United Kingdom. The empire’s reach is so great, in fact, that part owner Richard Caring is now floating his stake in the group at a gargantuan valuation of more than $1 billion. It’s enough to bring one out in a rash.

But let’s go back. In or around 1917, a small Italian café opened in Covent Garden to cater to theater-botherers, its name now lost to time. Run by owner Abele Giandolini and his maître d’, Mario Gallati, the place did a roaring trade early on among the local thespians, packaging up meals for them to eat in their dressing rooms. When Giandolini apologized to the actress Alice Delysia for some building work being done to the restaurant, she told him not to worry. “We will always come and see you,” she said. “We will cling together like the ivy.” The name stuck, and so did the glitzy clientele.