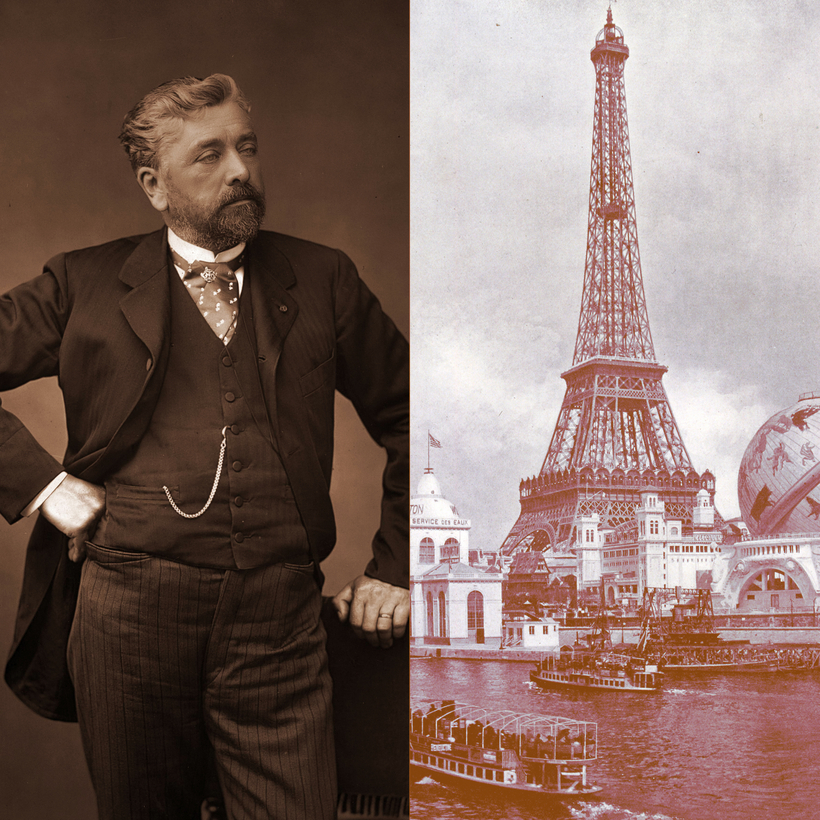

Gustave Eiffel is said to have joked that he was in danger of becoming jealous of his tower in Paris because it was more famous than him. He had a point. The Eiffel Tower has tended to eclipse the more than 500 other projects completed across 30 countries by France’s greatest engineer in the second half of the 19th century.

Now his descendants are seeking to use the centenary of his death to set the record straight. They are organizing events in France and around the world to highlight the extraordinary life and legacy of the so-called Magician of Iron.