In the late 80s, fresh out of college, I landed my first job in publishing as an editorial assistant at the Chicago Times, a smart start-up with big ambitions. One afternoon in August the editor in chief stopped by my desk to share the news that he had convinced the Welsh writer Jan Morris to come to town and write about the city.

“And I volunteered you to be her driver,” he told me.

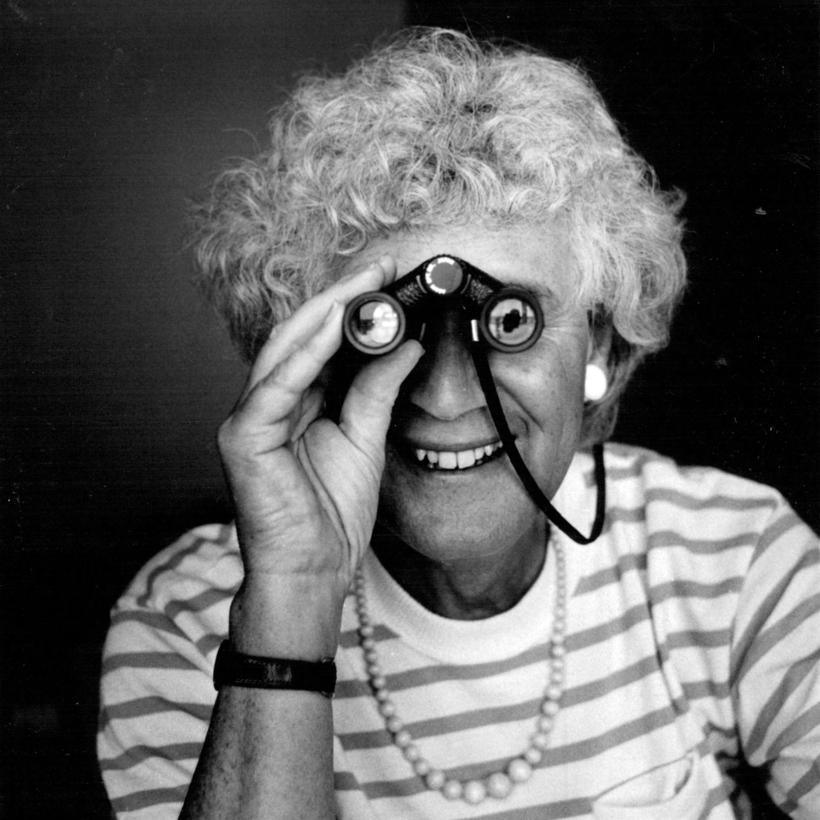

Two weeks later Morris, wearing a flower-print summer dress and a string of pearls, walked out of the Drake Hotel and squeezed into my 1972 Chevy Malibu. Over the next few days, as I drove her through the length and breadth of the city, from the remains of George Pullman’s factory town, where the storied railroad sleeping cars were built, to the leafy Gold Coast towns that unfurled up the shore of Lake Michigan, Morris treated me to a master class in writing and reporting.

(Lesson No. 1: Whenever you’re writing about a city, spend an afternoon in the criminal-courts building. “I learned it from Dickens,” she told me. “It’s the best way to understand the character of the city. Just open up a random courtroom door, sit down, and see the drama being written.”)

Morris’s place in the pantheon of journalism (where she broke in as a cub reporter at 16) and publishing was more than secure by the time she arrived in Chicago, aged 62—and would have been even if she had never done anything after May 1953, when, banging away on a typewriter from the advanced base camp at 22,000 feet, she broke the news and sent it via coded dispatch smuggled out with sherpas, of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s conquest of Mount Everest. It was the scoop heard round the world, landing on the front page of The Times of London on the eve of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

Morris, then just 27 years old, was only getting started. By the time she was 35, she had seen 75 of the world’s leading cities—a feat that, as Paul Clements notes in his new biography, Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, prompted Alistair Cooke to dub her “the Flaubert of the jet age.”

The ever restless, ever curious Morris would go on to write a staggering 58 books, three of which still endure for the new paths they forged in their respective genres: Venice, her mesmerizing, all-seeing portrait of the city, which redefined what “travel writing” could and should be; Conundrum, her riveting, groundbreaking memoir of her transition, at age 46, from James Morris to Jan Morris via surgery in Casablanca; and Pax Britannica, her majestic three-volume account of the peak and then the swift, disorienting dismantling of the British Empire during the 20th century.

Hers was a stirring, extraordinary life—she died, at age 94, in November 2020—that was astonishing no matter the measure, be it miles traveled, books written, or challenges met. Which is why one can’t help but feel a degree of sympathy for Clements and the challenge he has taken on here.

Having known Morris for more than 30 years, thanks in part to writing a critical study of her work in 1998, Clements aims to bring this unique perspective to a profile that touches down at a few pages over 600. For all Clements’s access to Morris, however, one comes away from this book feeling no closer to her. She’s like a compelling figure seen across the square of some exotic city that you long to know more about, but is then … gone.

At times you wonder if Clements’s tendency to veer toward minutiae (the price of each of Morris’s books when they were released; the 1950 circulation figures for travel magazines in the U.K.) is his grasping to bring some—any—level of detail to Morris’s life. But there are random details, and then there are essential details that burn in one’s mind, and the book most springs to life when Clements leans on Morris’s own writing, as when he quotes the remarkable moment from Conundrum when Morris is waiting to go under the scalpel:

“I sat on the bed in the silence and did The Times [of London] crossword puzzle: for if these circumstances sound depressing to you, alarming even, I felt in my mind no flicker of disconsolance, no tremor of fear, no regret and no irresolution. Powers beyond my control had brought me to Room 5 at the clinic in Casablanca, and I could not have run away then even if I had wished to.”

Clements’s best writing covers Morris’s early years, where he unpacks the early forces of wanderlust that formed the aspiring writer, and also reveals how Morris knew by the age of four that she was “not fully male.” But the reader can feel a bit as though Clements were one of those tour guides you see in European cities large and small, marching forward, holding a small pennant aloft to lead his charges from sight to sight as he or she dutifully retraces the paths of some long-gone great whose tale they know the chronology of, but not the soul.

Recounting the stories of a larger-than-life individual who was also a great writer is a steep challenge. Especially when the stories Morris left behind would overwhelm anyone’s attempts to find a better way to tell them. The comparison may be unfair, but it’s the peril of trying to capture a life and its drama that have already been told by Morris herself across 58 books.

Michael Hainey is a Writer at Large for Air Mail