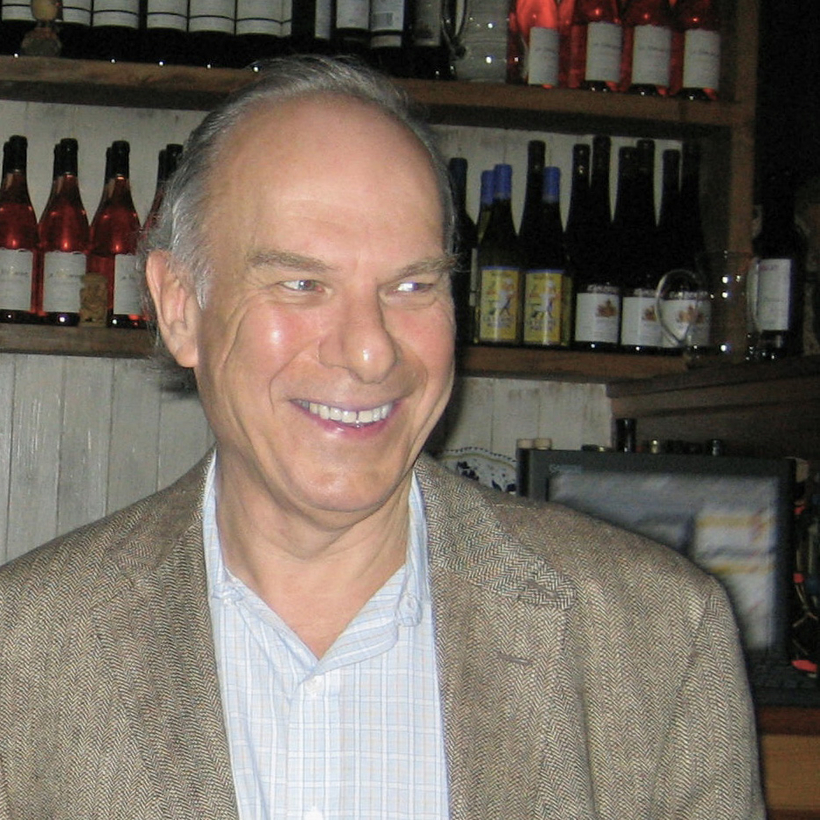

It may not sound like much, but those lucky enough to have had such figures in their lives will know exactly what I mean: John Heilpern was one of the few people in my childhood who treated me like an adult. He stooped, literally and figuratively, taking me to movies, making dates to play chess. (John could have thrashed me; he let me win. He certainly ought to have thrashed me when I crowed about winning.)

John once made the mistake of bringing my brother Ash and me to Beauty and the Beast—the animated one. He was reviewing it for The New York Observer and wanted our “expert” opinion. We rewarded John’s trust—and the small fortune he had spent on dinner and candy—with the verdict that the beast’s nose, on regaining his human form, was “too long.” Sixty years before, Ash and I would have been the screen-test geniuses concluding that Fred Astaire was slightly bald. He simply laughed—and could have done worse.