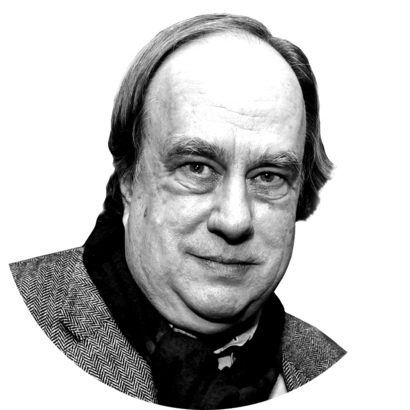

Climb into the wayback machine and return with us to the rowdy days of yore when intellectuals roamed Manhattan with woolly hair, rough manners, and often unruly tongues, ready to rumble at the drop of a syllogism. The date: April 30, 1971. The place: Midtown’s Town Hall. The event: “A Dialogue on Women’s Liberation,” sponsored by the Theater for Ideas, which sounds so civil and Socratic—hah. The Dialogue turned into a donnybrook. Second-wave feminism was coming into its fiery own, any debate about “women’s lib” was likely to turn testy and shouty, and this one had the buildup of a heavyweight bout. Serving as both M.C. and boo-hiss villain was Norman Mailer, whose recent The Prisoner of Sex, his coruscating counter-blast to Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, solidified his status as belles lettres’ reigning male-chauvinist ogre. His bold challenger was the Amazonian tower of power, Germaine Greer, whose feminist polemic The Female Eunuch struck like a thunderbolt on both sides of the Atlantic. Filling out the fight card were New York NOW president Jacqueline Ceballos, cultural essayist and critic Diana Trilling, described by one observer as “Western Civilization’s ambassador to the proceedings,” and The Village Voice’s resident sprite of Joycean riverrun prose, Jill Johnston, future author of the proclamational Lesbian Nation.

The ruckus that ensued between the factions in the audience and the combatants onstage was captured in all its rude glory by D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus in the 1979 documentary Town Bloody Hall. After being only spottily viewable for decades, Town Bloody Hall—its title taken from a burst of exasperation from Greer—has been canonized in a DVD/Blu-ray Criterion Collection package, with nifty bonus trimmings. Like the best cinéma vérité (Don’t Look Back and Gordon Sheppard and Richard Ballentine’s 1963 profile of Hugh Hefner, The Most), Town Bloody Halltranscends time-capsule dustiness by pulling the viewer so tight into the action that the hum of electricity becomes palpable.