In Sunset Boulevard, Norma Desmond said of her fellow silent-picture actors, “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.” She is sneering at the performers who came after her for relying on the crutch of speech, but of the golden era of sound movies that followed, one could fairly, indeed lovingly, say, “They had voices.”

Think of the salty crispness of Clark Gable’s voice—it’s like someone tearing the cellophane off a package of crackers—or Bogart’s slight whistle, or the soft, reedy tone of Henry Fonda that even in close-up sounds like he’s somewhere behind you in the distance. You could never mistake Katharine Hepburn’s goose-like timbre for Jean Arthur’s husky tinkle—Arthur has a girlish voice, but it’s a girl who smokes.

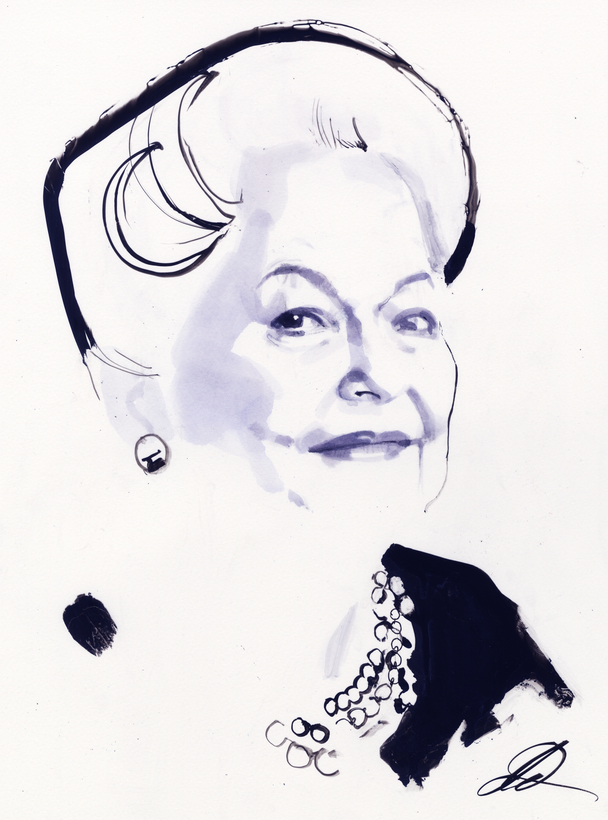

And then there is Olivia de Havilland, who died last week in Paris at 104. More so than even musical actors, de Havilland had a voice that was hypnotically melodic. She almost never went straight though a sentence—her voice rose and fell, giving even ordinary dialogue a kind of enchantment. Whenever she says “Scarlett” in Gone with the Wind, she holds the first syllable for two beats, the way one might in a song. (Gable rips right through it. ) Her voice is low but wooing, like a woodwind.

She started on the stage but wasn’t there for long. She did a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Hollywood Bowl, playing Hermia, and was quickly signed to a contract at Warner Bros., where they worked her hard. In four years, she made almost 20 movies, some better than others, and one a sublime and ageless classic: The Adventures of Robin Hood. De Havilland was as good as one could be in it, but the film is not called The Adventures of Maid Marian, and most of the focus is elsewhere.

Whenever she says “Scarlett” in Gone with the Wind, she holds the first syllable for two beats, the way one might in a song.

In 1939, she played Melanie Hamilton in Gone with the Wind, the big event of that year, in fact the big event of many years, and she was nominated for her first Oscar. (She lost to her co-star Hattie McDaniel.) Her ability to hold her own against Gable, Vivien Leigh, and McDaniel is all the more amazing because she had one of the hardest of all acting challenges: how to make us interested in a character of pure and utter goodness. Unlike Scarlett, Melanie never gives into her temper, never thinks ill of anyone, always does the noble thing.

De Havilland imbues Melanie with a depth of feeling that makes us see her as real, and once she is real to us, we can care what happens to her. Scene after scene is enriched by de Havilland’s emotional commitment: alone with Ashley at the Twelve Oaks barbecue; running to him as he comes home from the war; waiting for Ashley to return from a raid and deceiving the Yankee captain; the conversation in the carriage with Belle Watling; the walk up the stairs with Mammy after Bonnie’s death. My God, the walk up those stairs! Hattie McDaniel’s performance is so shattering, it would blow anyone else off the screen, but de Havilland holds our attention, too, and not through any tricks but through the extraordinary compassion of her presence.

This is de Havilland’s signature gift as an actress. She does not distract us with her ravishing beauty like Rita Hayworth or with a mannered idiosyncrasy like Bette Davis. What she does is invest herself fully in the humanity of whatever woman she is playing and make you believe, no matter how improbable, the situation. She won her first Oscar, for To Each His Own, with a cuckoo plot out of an afternoon soap, and yet more than once she brings you to tears. She believes it all so much you discard your cynicism and surrender to the story. (Don’t worry—your cynicism comes right back when it’s over and you turn on the news.)

She won her second Oscar for her performance in William Wyler’s emotionally ruthless The Heiress, based on a stage adaptation of Henry James’s short novel Washington Square. Her journey from a gauche, shy girl to a calculating, steel-cold woman is both heartbreaking and chilling. (It’s as though she started out playing Melanie and ended up as Scarlett.)

In the mid-2000s, I was in L.A. at the Four Seasons bar meeting with Mark Ruffalo about playing Perry Smith in my film Infamous. (He didn’t.) The bar was crowded and noisy, everybody loudly trying to get whomever they were with to do whatever they wanted. Mark is a good guy, friendly and smart, and we were having a great talk when I saw Mark blink as if he had seen something he couldn’t believe. I turned to see what it was.

Olivia de Havilland had come in.

And even in what-can-you-do-for-me Los Angeles, always about what’s next and embarrassed even to mention yesterday, everybody knew. And for a moment the room fell silent. It was not just an expression of awe, though it certainly was that, but I suspect of gratitude, too, because Olivia de Havilland did what we most of all want when we go to a movie: she made us forget and believe.

Douglas McGrath is a filmmaker and playwright. He lives in New York City