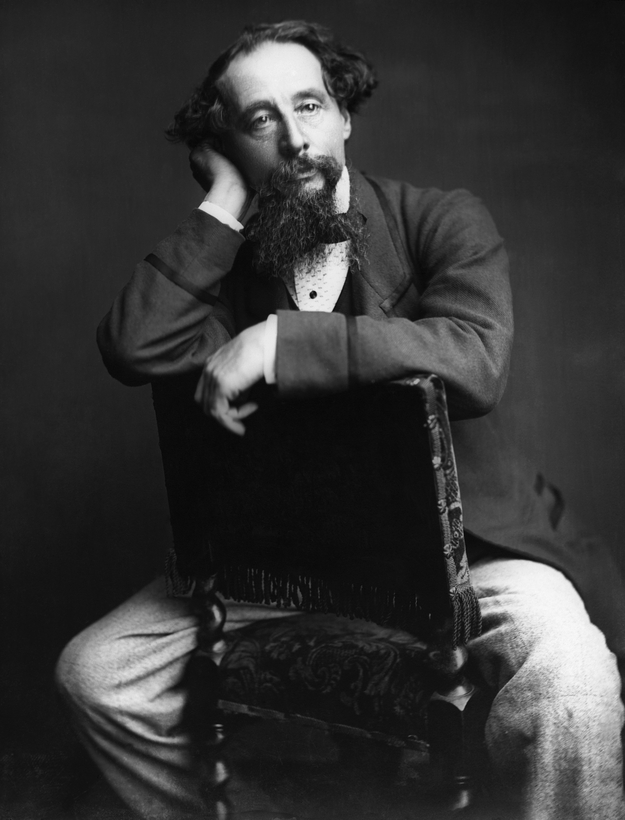

A.N. Wilson’s new book is called The Mystery of Charles Dickens. By the time I finished it I wondered if it might have been better titled The Monstrosity of Charles Dickens. Wilson’s Dickens is a diminutive, whiskery, prematurely decrepit monster of lust, ego and demonic capitalistic energy. He is the presiding monster of his age; a man driven half-mad by the cruelty, smugness, competitiveness and hypocrisy of the 19th century.

Wilson opens in 1870 with 58-year-old Dickens dying on the floor of the dining room at Gad’s Hill, his country home in Kent. He is (although not for much longer) “one of the most famous human beings alive”. Thanks to an exploding population and the increasing spending power of the working classes, Victorian Britain offered for the first time in the history of human civilization “an audience for popular entertainment to be numbered in the millions”. Dickens was the beneficiary of that cultural shift. Before his death he was “pursuing, and achieving, a level of human popularity that was without parallel”.