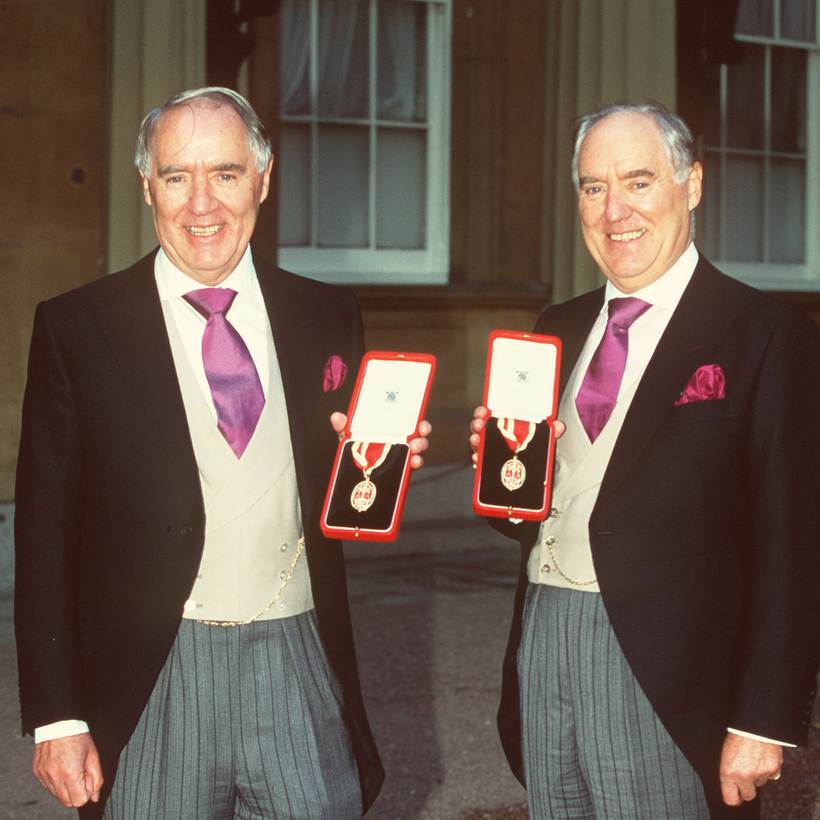

The most you can say about the Barclay brothers is that there’s not a lot you can say about the Barclay brothers. Or not much that you can get past your fact-checkers and lawyers, anyway. Secretive, reclusive, litigious, the eccentric identical-twin tycoons—who own the Telegraph newspaper, the conservative weekly magazine The Spectator, and the Ritz hotel in London, among other British institutions—have long been surrounded by a potent and shadowy omertà. There’s the fortress-like home on the private island of Brecqhou, which the pair bought in 1993 (according to local legend, the narrow sound that divides it from nearby Sark has only once been successfully crossed at high tide); the twins’ alleged abstention from text and e-mail; the fact that there exists just a single picture of them together on Getty Images, taken in the year 2000 on the occasion of their knighthood; and the ardor with which they pursue those that offend them in print. The Barclays are not shy of publicity—they are mortally allergic to it. Theirs is an oil painting with the eyes redacted.

It is a delicious irony, then, that the billionaire twins, now aged 85, have been splashed all over the press this past month thanks to a case of high-stakes eavesdropping and rank indiscretion. The saga wends from the alleged bugging of the conservatory at the Ritz, deep into the Barclays’ complex web of business interests and assets. But it is also the story of a family in the throes of a Lear-grade crisis, with a level of intergenerational suspicion that makes Succession look like Modern Family.