“The only thing that keeps me awake at night is the thought of a pandemic,” Bill Gates, the second richest man in the world, told us in an interview last February. “It’s been 100 years since we had a huge flu epidemic. People travel more today, so the speed of spread would be faster. If you had a respiratory transmitted disease, the numbers could be horrific.”

Not kidnapping, terrorism or losing his wealth but a virus. Now he kindly doesn’t say “I told you so” but admits: “My worst nightmare has come true.”

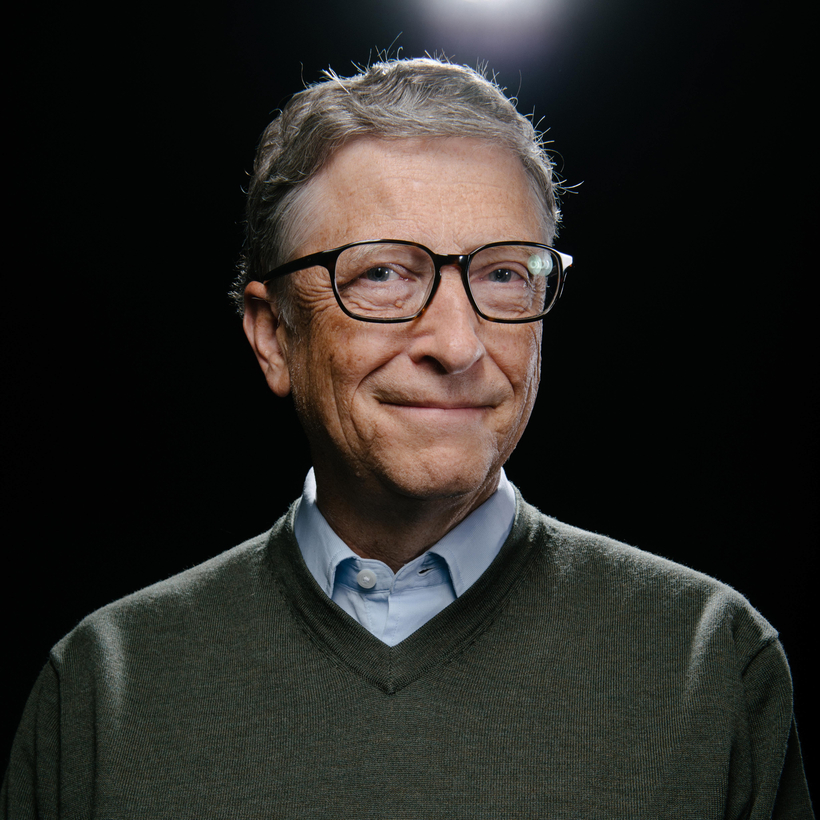

The $93 billion man who created Microsoft is also expert on vaccines, testing and treatments, having led the way, with his wife, in trying to “eradicate diseases” — first polio, then malaria and HIV — with their Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

He is obsessed with saving millions of lives and has always been highly aware of the dangers of another disease terrorising the world.

For the past three months, Mr Gates has been desperately trying to find a solution to Covid-19, his new nemesis. Unlike President Trump, who has suggested using disinfectant to conquer the virus, Mr Gates has always preferred facts, data and briefings from experts. He can reel off the population figures for every country in the world and he has prime ministers, epidemiologists, pharmaceutical CEOs and Nobel winners on speed dial.

In normal times, he criss-crosses the world, often travelling to Africa, China and India in a month, in his attempts to save lives from diseases. Now he is stuck in Seattle but is still wearing his trademark V-neck jumper, chinos, loafers and $10 watch. Unlike billionaires such as Jeff Bezos who has benefited from Amazon’s role in the world’s lockdown, or Sir Richard Branson, who has demanded a bailout for his business, Mr Gates’ sole mission is to take on the virus and win. “Anything else is a distraction. I don’t like to multi-task.” He doesn’t want gratitude, he wants annihilation.

The global fight against the virus is, he says, like a world war, “except in this case we’re all on the same side”. Everybody is reassessing their priorities and expectations. “In terms of shaping your view of government and life and what’s important, really jarring you … I think this generation will be forever marked by what goes on in this pandemic.”

Boris Johnson has had his own very personal experience of Covid-19. Does Mr Gates, who struggles to be charitable about Mr Trump, think that the politicians are up to the challenge? “You go to war with the leaders you have,” he replies. “In retrospect you get to judge how well that went. I do think the fact that the world was moving towards nationalism and countries taking care of themselves, that framing is not helpful. We all wish we had raised the rallying cry more quickly. Very few people get an A in terms of what they’ve done in this situation.”

Unlike billionaires such as Jeff Bezos who has benefited from Amazon’s role in the world’s lockdown, or Sir Richard Branson, who has demanded a bailout for his business, Mr Gates’ sole mission is to take on the virus and win.

He doesn’t think governments have over-reacted by imposing lockdowns. “Certainly the economic impacts are unbelievable — electricity use in some places is down 10 per cent, the unemployment numbers are mind-blowing — but human behaviour is not a totally flexible thing that leaders can turn on and off. As soon as the epidemic was well known some of the public was going to choose not to get on a plane, not to go into work, not to have their kids go into school, whatever their government said.”

There would, he argues, have been a devastating impact on businesses in many countries in any case. “You could have had the worst of both worlds” with “both a terrible economy and growing disease numbers”. That would have had a cumulative effect. “If you got up to the millions of deaths then more and more people would change their behaviour so you would get to an extreme situation.

“The idea that a hotel with a 30 per cent flow, or a restaurant that is 30 per cent full would stay in business doesn’t show an understanding of the economy. People act like if we just went for herd immunity and let it rip the economy would have been fine but that counterfactual does not exist. The economy in these rich countries that are experiencing the epidemic was going to be really terrible.”

Failure is not a word with which the Microsoft founder feels comfortable. He is determined that the world will get back on track, but he says that science, not politics, holds the key to solving the crisis and preventing future pandemics, with rapid innovations in testing, treatment and vaccines. His Gates Foundation will help to mobilise the money needed to fund the building of factories that will be ready to manufacture billions of doses of several different vaccine candidates even before one of those inoculations has been approved in order to speed up the process. He is in touch with all the most innovative programmes. Sarah Gilbert, head of the Jenner Institute’s influenza vaccine and emerging pathogens programme at the University of Oxford, is “wonderful”, he says, and that is “one of the great efforts going on”.

At the moment the government has given enough funding to ensure the research in the UK can go “full steam ahead” but Mr Gates is already speaking to pharmaceutical companies about scaling up production of the Oxford vaccine if it looks like it could work. “They are going to put it in humans fairly soon … if their antibody results are one of the ones that are promising then we and others in a consortium will help make sure that massive manufacturing gets done.”

He says the aim must be to produce vaccine for the entire world. He is determined western governments cannot hoard vaccines and treatments that will also be desperately needed by developing countries and he is hoping that the online Coronavirus Global Response Summit next month will raise more than $8 billion from governments and organisations for research, development, production and distribution.

“Fortunately nobody doing the vaccines expects they’re going to make money on them,” he says. “They know this is a public good — partly because they will need indemnification as part of the regulatory approval, which will have to be expedited. Three months after you dose the humans you will see those responses and you will know at that point. Maybe there will be four or five that we will build factories for even though in the end we may only use one or two of them. That compresses the time.”

He doesn’t like being thought of as a do-gooder, but he worries that poorer nations will suffer most. The Gates Foundation’s other trials for HIV treatments and polio campaigns have been put on hold to focus on the coronavirus pandemic. “Whenever something bad happens it’s worse for the developing countries than the developed countries … Even though the numbers right now are pretty small out of the developing countries, unless there’s some factor we are not aware of it’s likely that the vast majority of the suffering and deaths will be there, particularly in the urban slums. Even in developed countries the suffering of the low-income there is disproportionate and tragic. This is a huge blow against the quest for greater equity in the world.”

“Fortunately nobody doing the vaccines expects they’re going to make money on them,” he says. “They know this is a public good.”

Mr Gates has spent the past two decades trying to mitigate his wealth, preferring whiteboards to superyachts and Diet Coke to champagne. Other billionaires have retreated to their bunkers, or snapped up land in New Zealand with an airstrip for their private jets as “apocalypse insurance”. Mr Gates says: “We aren’t all best friends.” He has paid more than $12.4 billion in taxes personally and, with Melinda, has pledged to give away the majority of his wealth rather than pass it down to his three children. In the lockdown it is not his private jet that he misses but going for a drive-through burger. He refuses to cut himself off from the outside world. “My days are talking to biotech people. People send me ideas for therapeutics on email, we dig into those, a few are promising.”

He won’t criticise other members of the super-rich elite but he says that he has had a rise of interest in The Giving Pledge, the scheme he founded with Warren Buffet which encourages billionaires to give away half their wealth. “Some people are stepping up philanthropically to help out, we are having lots of calls.”

He may be working from a $100 million home with his wife and their children, Jennifer, Rory and Phoebe, aged 23, 20 and 17, but he has always done the washing up and the children lay the table. “It’s weird, nobody has been into the foundation offices now for over a month. Even though this is a terrible situation I’m actually surprised we are able to get a lot of our work done.” He and Melinda meditate every day and read voraciously. “You are with your kids a lot. That’s nice in a way, but college-aged kids didn’t expect to be with their parents as much. I don’t think our situation is different from most. We’re not crowded in because we have space but our lives are utterly changed.”

He would love to think that this will be a moment in which the world’s priorities can also be reset. However, the 21st century missionary and disease hunter is not starry-eyed about the chances of global redemption. “I do see a lot of people, taking whatever ideas they had before the epidemic and saying, ‘Now that money is free, fund my thing.’ I hope in terms of countries working together on tough problems, including climate change, this is helpful, but here in the thick of it it’s very difficult to predict.”

Last year he said he was a natural optimist and seemed convinced that in the end humans could crack everything from Alzheimer’s and HIV to obesity and diabetes. “There’s no way to view this as net positive, this is a terrible thing that’s happened,” he says. “Maybe we will get some insights into ourselves and the benefit of co-operation but I’m not at the point of trying to figure that out.”