For all its posterior romance, 18th- and 19th-century Egypt was something of an acquired taste for the Westerner. Eliza Fay, an intrepid and self-possessed traveler, stopped over in Alexandria in 1779. Observing Mount Horeb on her passage down the Red Sea, she was reminded of the “flight of the children of Israel”: “And you may be sure, I did not wonder that they sought to quit the land of Egypt, after the various specimens of its advantages that I have experienced.” One man’s (or, for once, woman’s) trash, another’s treasure. Toby Wilkinson’s cracking A World Beneath the Sands: The Golden Age of Egyptology abounds with alternative, more appealing “specimens.”

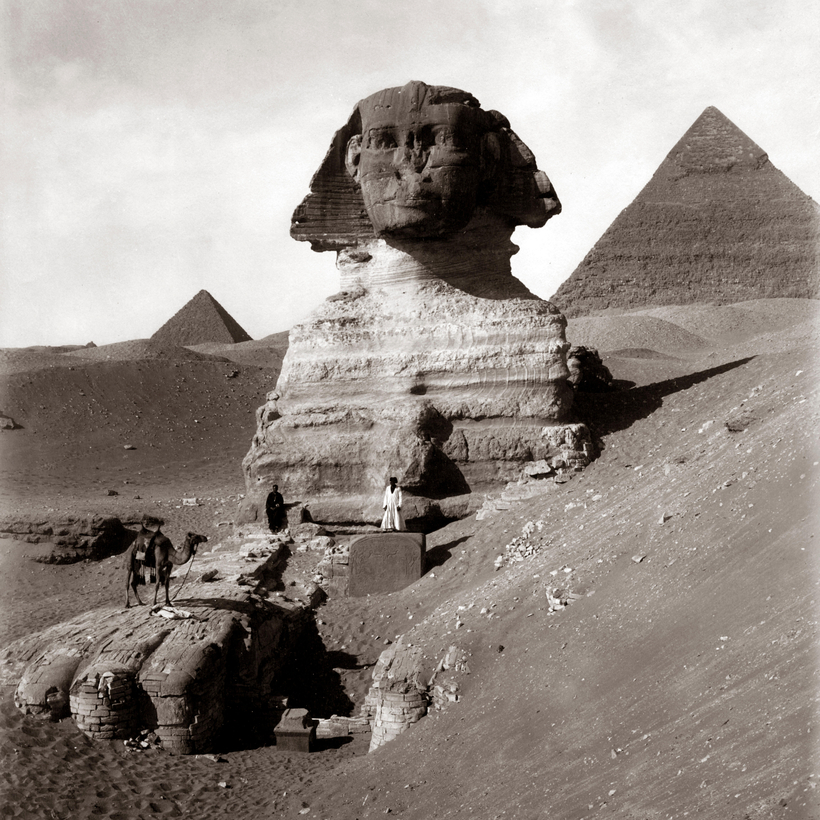

Before Napoleon descended on North Africa, ancient Egypt was shrouded in centuries of mystery and—Wilkinson’s title is no exaggeration—sand. The Roman emperors Julius Caesar and Hadrian made celebrated tours. Records of subsequent foreign visits are spottier. Arabic scholars turned up in the 12th and 13th centuries, including Jamal al-Din al-Idrisi, who wrote the earliest known text on the pyramids. With the Turkish conquest of the Nile Valley in 1517, European interest—animated by the “first stirrings of Renaissance thought”—and access resumed. Firsthand accounts veered between an idle mysticism and impressive guesswork. The 17th-century grand tourist George Sandys surmised that the pyramids were royal tombs. In 1726, the versatile Jesuit missionary Claude Sicard identified the ruins at Luxor as the “hundred-gated Thebes” of legend. Yet these were solitary amateurs. It would take the convergence of the French Revolution’s imperial pretensions and Enlightenment ideals to set the foundations for Egyptology.