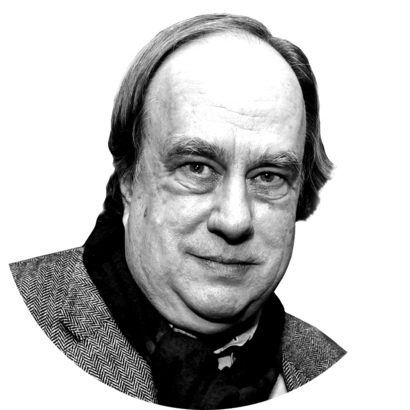

Issuing a gruff dissent on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, Kingsley Amis cast a scowl at the baroque exhibitionism of Nabokov’s style, singling out the garish description of Charlotte Humbert’s hit-by-car accident, which, wrote Nabokov, left “the top of her head a porridge of bone, brains, bronze hair and blood.” Amis: “That’s the boy, Humbert/Nabokov: alliterative to the last.” In the first chapter of actor-director Sean Penn’s novel Bob Honey Sings Jimmy Crack Corn, the follow-up to last year’s Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff, a mangled body yields a goulash of “blood, brain, and brutal bits,” and one can only sigh, That’s our Penn, alas: alliterative from the start.

And he never stops. Alliteration runs amuck: “Head in habit and honing Hebrews,” “Mockery is midget-minded misunderstanding,” “the pencil piñata of a person bleeds the confetti of plagiarized pop paeans,” “the parental pitfalls plaguing so many of his playmates,” “her whiskey-wee parts the wings of her wizard’s sleeve-thing,” and this doozy, “gangrenous dormant derma of human disposition.” For troubadour effect, Penn occasionally renders sentences as rhymed couplets—“Gutters stream, puddles plop deep, but life goes on after the prior night sky’s worrisome weep”—but then he’s back to his favorite tic, alliterating to beat the band, the “tappity-tap of the pileated pecker plundering pulp with pride in its plumage.” No matter how hard you try to tune it out, you can’t read this tale without being subjected to the unstoppable tappity-tap of Penn’s pileated pecker.