Founded in 1972, the imprint Lost American Fiction had a mission to reintroduce wrongly forgotten books. It had reprinted 29 of them by 1979, at which point the series was itself consigned to oblivion. Prion Lost Treasures brought out 26 before suffering the same fate. Ecco Neglected Classics only made it to 21. There is something poignant about coming across a volume labeled “lost” or “neglected” in a used-book store, the designation having become prophecy, but the earthward trajectory of these quixotic enterprises is unfortunately all too predictable.

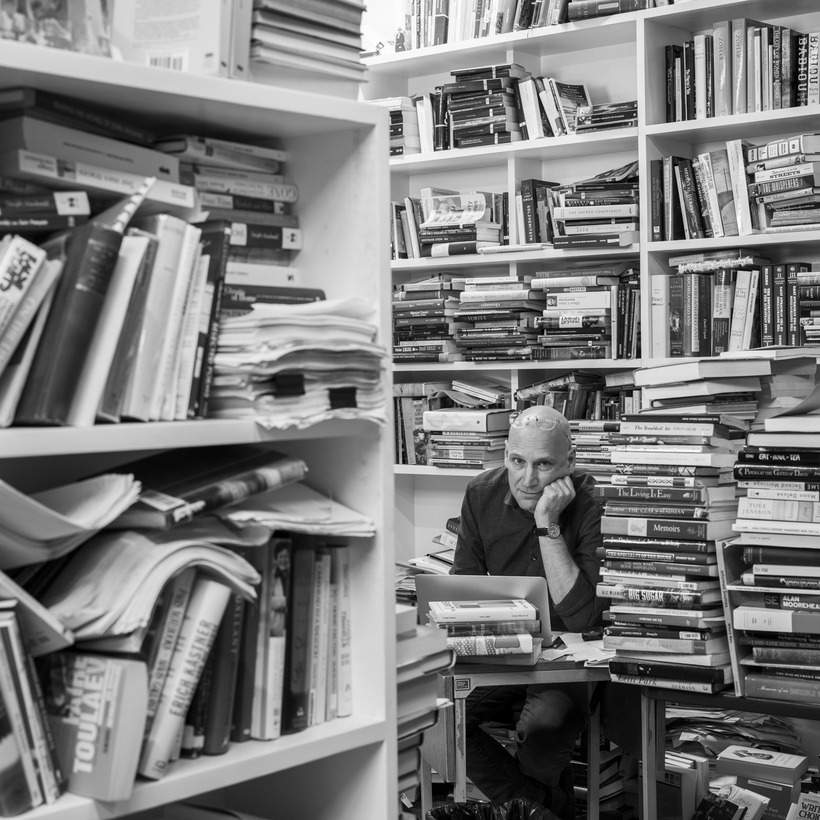

Which is why the 20th anniversary of New York Review Books Classics—they hit 500 last year, with Wolfgang Herrndorf’s Sand—is such an improbable milestone. That an imprint devoted to out-of-print texts and works in translation has managed not just to weather the new millennium’s disruptions but to grow—and even to spawn imitators—is nothing short of a miracle. It would be difficult to think of a less commercially minded venture in the early 21st century, and only someone innocent of any publishing experience could have made it a success. This week, one of the writers they publish, Peter Handke, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, a decision that was met with controversy because of Handke’s views during the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. “Just last night I was saying he’d never get the Nobel because of his political history, but I am happy to be proved wrong,” said Edwin Frank, the founder and editor of NYRB Classics, in an e-mail the morning of the announcement.