Long before Kenneth Chesebro became Co-Conspirator 5—which is how he was identified in the indictment of Donald Trump for attempting to overturn the 2020 election—he was “the Cheese,” his nickname at Harvard Law School in the mid-80s. The moniker was based in part on a corruption of his name, which is pronounced “chez-bro,” as well as a reference to his Wisconsin roots. But there was also an element of irony in the choice, because Chesebro was anything but a big cheese—rather, a shy, awkward nerd among nerds.

So, it appears, Chesebro remained through most of his adulthood, which has rendered his current notoriety a source of bafflement to those who have known him since those days. Chesebro’s role as a legal architect of Trump’s efforts to remain in office after he lost the presidential election came to light months ago, but the indictment, which Special Counsel Jack Smith obtained from a Washington grand jury last week, places an especially harsh spotlight on Chesebro’s conduct.

As a result, his own legal status appears precarious at best. Chesebro may be indicted; he may continue to take the Fifth and hope to stay out of Smith’s line of fire. Smith’s team surely hopes he will plea-bargain and then testify against Trump. The only certainty is that in the most important criminal trial in American history, the Cheese, whether he is offstage or on, will be a central figure.

Chesebro was anything but a big cheese—rather, a shy, awkward nerd among nerds.

Chesebro was born in 1961 and grew up in a small town in central Wisconsin, where his father was a public-school music teacher. Ken was a competitive debater in high school and college, at Northwestern, and when he arrived in Cambridge for law school, in 1983, he looked much as he does now: the same shock of brown hair flopping onto his forehead, the same aversion to eye contact. He did well at Harvard and made Law Review, but his social skills never matched his academic achievements. “I will never forget what happened once in the typing room,” one former fellow student recalled. (In those days, students could choose to write their exams by hand in blue books or type them in a separate room on their Smith Coronas.) “First, Ken shows up with two typewriters—one and a backup—which I had never seen before,” the student went on. “Then, with about 15 minutes left in the exam, a woman starts panicking because her typewriter has broken. She notices that Ken has two, and she asks him to borrow one for the last few minutes. He says no and tells her, ‘Harvard Law School is a dog-eat-dog place.’”

In the 80s, Harvard Law School was also a politically polarized place. On the faculty and in the student body, the far-left critical-legal-studies movement was a major presence. The early days of the Federalist Society drew a vocal minority on the right. In the law school’s ideological center, which resembled the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, the dominant figure was constitutional-law professor Laurence Tribe, who attracted like-minded students as research assistants on his scholarly work and court cases. In this period, Tribe’s student assistants, in what was known informally as “Tribe World,” included Elena Kagan, the future Supreme Court justice; Ron Klain, later President Biden’s chief of staff; and Chesebro. (Chesebro and I were law-school classmates, and I, too, worked for Tribe.) “I gave him some assignments, and he did them well,” Tribe tells me. “He was very eager to please.”

For most of Tribe’s assistants, the job consisted of channeling the professor’s views, but Chesebro took a different approach. “Ken gets so fascinated with ideas and arguments, and if it’s something novel, he liked it better,” another Tribe assistant tells me. “He loved to dream up stuff that no one else thought of. The practical implications were always less important to him.” Tribe himself saw the occasional need to rein in Chesebro. “I’m somewhat adventuresome in the way I connect things, but Ken would often go too far out for me. There was a lack of judgment.”

After graduation, in 1986, most of Tribe’s protégés scattered to judicial clerkships and other jobs. Chesebro moved to Washington to work for District Judge Gerhard Gesell, who would soon become famous for presiding over the trial of Oliver North. Chesebro was an eccentric presence in Gesell’s chambers. “The judge would often walk to work early in the morning from his home in Georgetown,” a former Gesell clerk tells me. “One morning he arrived at about seven, and he found Ken sleeping on the couch in the office. He was living in chambers.”

In this period, Laurence Tribe’s student assistants included Elena Kagan, the future Supreme Court justice; Ron Klain, later President Biden’s chief of staff; and Chesebro.

After his clerkship, Chesebro made an unusual career move for a Harvard Law grad. He returned to Cambridge, and Tribe World, and set up shop as a solo practitioner, which he has remained for nearly four decades. At first he worked mostly for Tribe and with the professor’s other research assistants. For a 1989 Harvard Law Review article subtitled “What Lawyers Can Learn from Modern Physics,” Tribe, in a footnote, acknowledged the help of Chesebro and another, more recent research assistant—Barack Obama. (Tribe tells me Chesebro and Obama worked on different parts of the article.)

Later, in 2004, Tribe invited Chesebro to a fundraiser for Obama in his race for the Senate. “I was very impressed with him when he [Obama] worked for you in the late 80s, and have followed his work since then, particularly his community organizing work,” Chesebro replied. “I know you’ve helped to advance his career since law school, and wouldn’t be surprised if you had something to do with him winning the keynote speech, which of course was fabulous. His exposition of themes of union and common interest compares well with the speeches of Webster and Lincoln.... Webster and Lincoln are among the handful of leading American politicians who actually wrote their own speeches, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Barrack [sic] is in that group too; otherwise I don’t know how to account for the power of the speech’s fusion of biography, substance, and spiritualism.... He’d make a pretty good Supreme Court justice. It’s not often that someone comes along who’s capable of playing a lead role in all three branches of the federal government, and whose mere presence on the national stage is such an inspiration.... Anyway, I’d be happy to contribute to his campaign, though probably only the $500 minimum (I’m also contributing this cycle to my home state senator, Feingold, who frankly probably needs the help more.)”

From the late 80s forward, Chesebro continued to work on briefs with Tribe, but he also took on his own clients. His practice consisted almost exclusively of brief-writing for plaintiffs in civil litigation, often in personal-injury cases or class actions. As he put it in his LinkedIn profile, “Kenneth Chesebro has handled more than 100 cases in the U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts, frequently on behalf of trial lawyers pursuing high-profile litigation against corporations.” This kind of work has a strong ideological flavor. The lawyers such as Chesebro who represent plaintiffs are overwhelmingly Democrats; the lawyers for the corporations are generally Republicans. In a rare venture into legal scholarship, Chesebro in 1993 wrote an 89-page article in the American University Law Review defending the plaintiffs’ bar and skewering “Reagan Administration ideologues and their colleagues in Congress.”

Chesebro’s political contributions in those days went only to Democrats, including $1,000 to Senator Russ Feingold, the Wisconsin Democrat; $1,000 to the Clinton-Gore ticket in 1996; and $1,000 to Senator John Kerry in 2000.

“He loved to dream up stuff that no one else thought of. The practical implications were always less important to him.”

In Cambridge, Chesebro lived a quiet and stable life. In a 1994 wedding in Bermuda (which Tribe attended), he married Emily Stevens, a physician who later went to law school and occasionally co-wrote briefs with him. Their home was a modest apartment across the street from the Harvard campus. Chesebro spent long days researching and writing in the law school’s Langdell Hall library, where, over time, he became what appeared to be the oldest patron. Chesebro was a respected figure in the plaintiffs’ bar, often called on to write (or ghostwrite) briefs on challenging legal issues. He maintained an enduring, puppyish devotion to Tribe, who still, on occasion, hired him to help with his cases.

Notably, the last time that a presidential election ended in legal controversy, Chesebro put his skills to work for the Democrat. He assisted Tribe in his representation of Al Gore in the Supreme Court after the 2000 election. In a dense memo, dated November 27, 2000, to another member of the Gore legal team, Chesebro strategized about how Gore might prevail when the electoral votes were counted, on January 6, 2001. “Gore is toast unless the Florida Supreme Court orders the Governor to certify the Gore electors with the Seal of Florida,” Chesebro wrote.

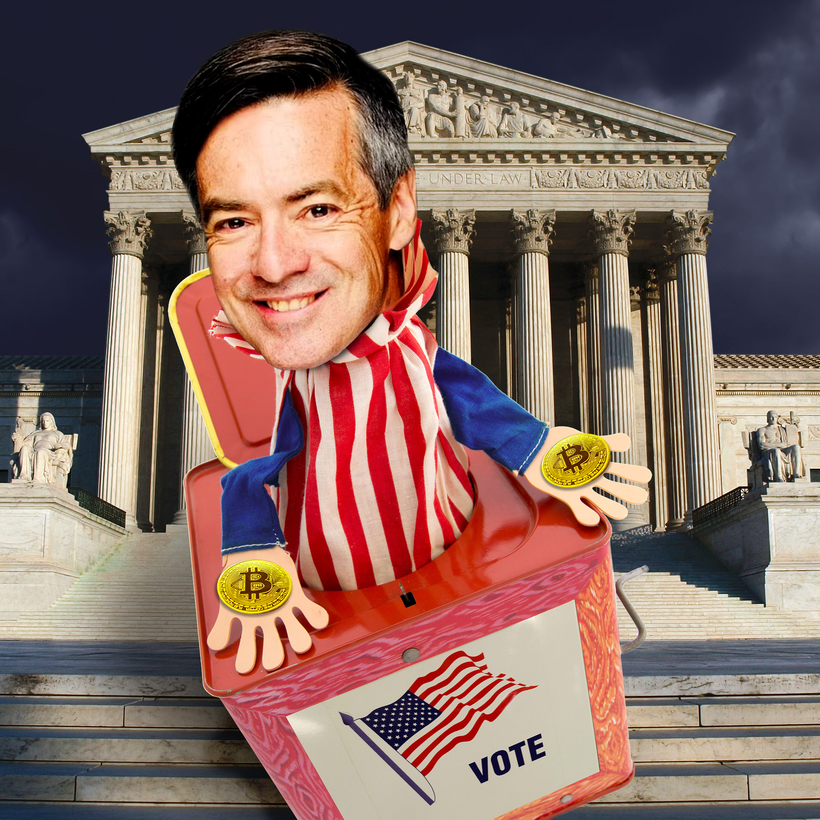

When Chesebro reached his early 50s, in the 2010s, he experienced what may be one of the more consequential midlife crises in American history. He began investing in crypto—and made a fortune. “In January 2014, I invested in Bitcoin on the conservative assumption that there was an 80 percent chance I’d lose everything, but a 20% chance that my Bitcoin shares would rise 10 fold within a decade,” he wrote in a later e-mail to Tribe, “so that on a risk-adjusted basis, I’d expect to double my money in ten years. As things turned out, my investment multiplied 20 fold by the time I sold just four years later.” (Chesebro sent Tribe several e-mails encouraging him to invest with him in Grayscale, a crypto-investment house. “I can personally vouch for the Grayscale people, having been lucky/smart enough to make several million dollars. ” Tribe passed.)

At around the same time, Chesebro split with his wife of more than two decades and transformed his lifestyle. According to a family friend, he moved first to an apartment in the Ritz Carlson Residences, on Boston Common, then to one in the city’s trendy Seaport district. Later, he moved to New York and bought a penthouse apartment at 230 Central Park South, a tony address in Manhattan. (The adjacent penthouse is currently on the market for $13.95 million.) Around his 60th birthday, Chesebro began courting a young woman, providing trips around the world, including an extended one to Paris and London to celebrate her 21st birthday. According to the family friend, the couple has since married. (Chesebro, through his lawyer, declined to answer questions about his marital status or anything else.)

Chesebro’s crypto jackpot was followed by a political transformation. Over the past several years, he became an active part of the conservative legal movement. In 2016, Chesebro filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court in a case involving the rights to citizenship of residents of American Samoa. His co-author was John Eastman, a onetime professor at the Claremont Institute, with whom he later worked on the Trump plan to overturn the 2020 election. (Eastman is Co-Conspirator 2 in the Trump indictment.)

“Gore is toast unless the Florida Supreme Court orders the Governor to certify the Gore electors with the Seal of Florida,” Chesebro wrote.

In 2018, Chesebro represented Senators Ted Cruz and Mike Lee, among other Republican politicians, in an amicus brief in the Supreme Court in a voting-rights case out of Utah. His co-author on that brief was James Troupis, a former Wisconsin judge who would also play a role in the effort to install Trump as president in 2021. In this period, Chesebro started making large donations to Republican political candidates, after having given nothing to anyone since 2000.

In 2020, Chesebro gave $2,800 (the maximum allowed) to Trump’s presidential campaign, as well as the same amount to Senator J. D. Vance, in Ohio. His biggest donation, $5,800 (covering two elections), went to Ron Johnson, the Wisconsin Republican who defeated Senator Russ Feingold. Chesebro had donated to Feingold in 1992 and supported Feingold in his 2004 e-mail to Tribe, but times, and Chesebro, had apparently changed. In all, over the past several years, Chesebro has given more than $50,000 to various Republican politicians.

In the months after January 6, 2021, the riot at the Capitol drew intense public scrutiny, including over the question of whether Trump bore criminal responsibility for the violence. But in crafting his indictment, Smith elided that issue, apparently fearing that Trump could successfully defend his encouragement of the rioters as an exercise of his right to free speech. Instead, Smith built his case against Trump around what the prosecutor called a conspiracy to convene “sham proceedings in the seven targeted states to cast fraudulent electoral ballots” for Trump. When Congress assembled to accept the results of the election, on January 6, the idea was for these fake electors to cast their states’ votes for Trump even though their voters had supported Biden. The person who came up with the fake-elector scheme was Ken Chesebro.

Chesebro became entwined in the Trump effort when Troupis reached out to him. In his deposition before the congressional January 6 investigating committee, Chesebro testified that Troupis—the “lead attorney for Trump in Wisconsin”—called him on November 9, which was six days after Election Day and two days after the national race was called for Biden. (In that deposition, Chesebro refused to answer most questions, citing his rights under the Fifth Amendment and his obligation to protect attorney-client confidences.)

Working for Trump pro bono, on November 18, Chesebro sent Troupis his first legal memo in the case. At the time, the Trump campaign was still considering whether to ask for a recount in Wisconsin (which Biden won by 20,000 votes), so Chesebro addressed the issue of deadlines: When did a final vote total have to be certified by the state? Federal law said a state’s electors had to convene to be certified at the state capitol on December 14. But in the memo, which repeatedly cited the work of his mentor, Tribe, Chesebro suggested that the Trump campaign could pursue legal challenges past that date; he said the only real deadline was January 6, 2021, when the House and Senate were to meet in a joint session to count the electoral votes.

The person who came up with the fake-elector scheme was Ken Chesebro.

But what could Trump do if the official tally still showed Biden ahead in Wisconsin and the other states on December 14? Chesebro—exercising the kind of legal creativity that had been his trademark since law school—came up with a novel idea. He suggested that “the ten electors pledged to Trump and Pence meet and cast their votes on December 14”—while those pledged to Biden, the real winner of the state, met in the capitol, in Madison. The ceremony for the Trump electors would serve as a kind of backstop while “the post-election process of recounting and adjudication” was underway. If somehow the courts ruled that Trump had won the state, his electors would already have met; if Biden’s victory was ratified, the ongoing process would simply continue, and Wisconsin’s electoral votes would count for Biden on January 6.

If the November 18 memo had been the extent of Chesebro’s involvement, it’s unlikely that he would be in legal trouble, or even that his role would be noted today. He was merely proposing an option (albeit a far-fetched one) to preserve the status quo while the legal process of resolving the election in Wisconsin played out. Chesebro’s problems arose out of what happened over the next six weeks. In a series of meetings and memos, Chesebro changed his approach. Instead of using the idea of alternate electors “to preserve rights in Wisconsin,” in the words of the indictment, Chesebro proposed that the alternate-elector process “instead be used in a number of states as fraudulent electors to prevent Biden from receiving the 270 electoral votes necessary to secure the presidency on January 6.” Starting on December 6, the indictment went on, Chesebro wrote memos that “suggested that the Defendant’s electors in six purportedly contested states (Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) should meet and mimic as best as possible the actions of the legitimate Biden electors, and that on January 6, the Vice President should open and count the fraudulent votes, setting up a fake controversy that would derail the proper certification of Biden as president-elect.”

Chesebro’s memos from this period make bizarre, even chilling reading. Chesebro’s detailed memo of December 6, which was first revealed in full by The New York Times this week, spelled out how the plan would unfold. The Trump electors would meet on December 14 “even if Trump has not managed by then to obtain court decisions (or state legislative resolutions) invalidating enough results to push Biden below 270.” Vice President Pence, presiding over the House and Senate on January 6, would recognize the Trump electors as genuine even though “the Supreme Court would likely end up ruling” that he had no right to do so.

As Chesebro put it in a December 9 memo, “Even though none of the Trump-Pence electors are currently certified as having been elected by the voters of their State, most of the electors … will be able to take the essential steps needed to validly cast and transmit their votes.” In other words, even though none of the Trump electors were electors, they could still validly cast their votes.

In the 2010s, Chesebro experienced what may be one of the more consequential midlife crises in American history. He began investing in crypto—and made a fortune.

Chesebro wasn’t just spitballing. Based on his legal advice, the fake electors did meet in the contested states, and their phony certifications were presented to Congress. On December 23, Chesebro and Eastman wrote to their legal team that “7 states have transmitted dual slates of electors”—which they did not, because there is no such thing as “dual slates of electors.” The names on the Trump slate were not any kind of electors, and the documents they transmitted to Congress were no more authentic than if they had created their own driver’s licenses. Trump himself tried to persuade Vice President Pence to use the existence of the fake electors as a reason to delay certification of the election. In doing so, according to the indictment, Trump committed a crime.

The question, then, is whether Chesebro’s underlying legal advice was also criminal. Chesebro has given only one news interview since his name came to light, and his defense of his conduct was straightforward. As Chesebro told Talking Points Memo in June, “It is the duty of any attorney to leave no stone unturned in examining the legal options that exist in a particular situation.” In the abstract, this is a fair point; lawyers should have broad latitude to come up with strategies to defend their clients. The issue is when legal advice is so bad that it encourages criminal activity. A lawyer who tells a client that he has the right to pull a gun and hold up a bank teller would surely be prosecuted. Was Chesebro’s advice that bad? In real time, he appears to have had at least some misgivings about his own plan. In a December 11 e-mail to Rudolph Giuliani (Co-Conspirator 1) and others on the legal team, Chesebro expressed the fear that their plan “could appear treasonous.”

While Chesebro’s fate in the Smith investigation remains uncertain, he is already the subject of an ethics complaint that could result in his disbarment in New York. According to a letter sent by several dozen distinguished lawyers to the bar authorities last October, Chesebro, as “the apparent mastermind behind key aspects of the fake elector ploy,” caused “serious harm to the public, the legal system, and the profession—indeed, to our democracy.”

Most painful to Chesebro, no doubt, is that one of the signatories to the bar complaint is Tribe, Chesebro’s old mentor. A longtime Trump critic, Tribe is especially aggrieved that Chesebro used his experience in Tribe World in the 2000 Bush v. Gore contest, and even cited Tribe’s own work, as justification for his effort in 2020.

“Ken grossly misrepresented my work in 2000 and everything I believe,” Tribe tells me. “And he was trying to do the opposite of what we were trying to do. We were trying to get recounts to identify the will of the voters. What Ken was doing was trying to overrule the will of the voters. It’s important not to penalize people for making creative legal arguments, but it’s another thing to make up legal arguments that have no legal basis. Creative lawyering can be distinguished from fraud. Even though we used to be friends, I really think he should never again be allowed to practice law.”

Jeffrey Toobin is a legal analyst and journalist whose latest book, Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism, is now available in bookstores