In the March 24, 1986, issue of The New Republic, an unsigned editorial by Charles Krauthammer made “The Case for the Contras,” endorsing Ronald Reagan’s plan to aid the anti-Communist group battling the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. For the opposing view, uncommitted readers had only to turn to the preceding page, which carried a pseudonymous TRB column by the magazine’s editor, Michael Kinsley, calling the president’s arguments “preposterous.” It was like opening the mail and finding two letters from the same charity: one urging you to donate to a particular cause, the other explaining why it’s a scam.

T.N.R. staff writer Jefferson Morley piled on in the next issue with “The Contra Delusion.” A pro-Contra dispatch by Fred Barnes appeared the following week, along with a second Contra-skeptical TRB column, and a back-page Diarist, by the magazine’s publisher, Martin Peretz, who made it clear that he shared Krauthammer’s views, even if his colleagues at Harvard, his wife, and “at least one” of his two children did not.

The issue after that contained half a dozen harshly critical letters on “The Contra-versy,” stirred up by Krauthammer’s editorial, one of which had been drafted by T.N.R.’s former (and future) editor Hendrik Hertzberg, and signed by 13 of the magazine’s 18 contributing editors, including the political theorist Michael Walzer, one of Peretz’s closest friends. And it wasn’t just liberals who were outraged. Elliott Abrams, the architect of the policy at issue, was so incensed by Peretz’s refusal to maintain discipline in the ranks that he canceled his subscription.

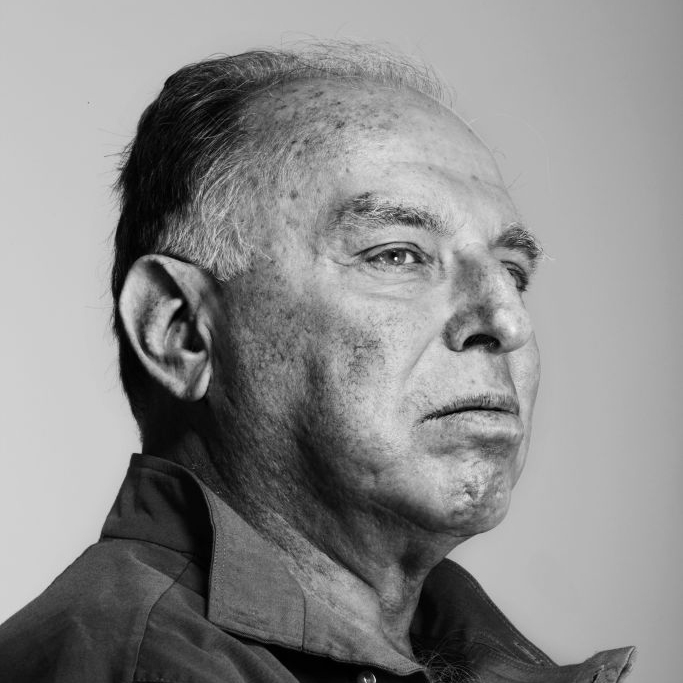

Peretz looks back on the mêlée with evident fondness in his new memoir, The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone, Left Right and Center. “The contradictions existed—but in a way that was the point, even if it made us enemies on both sides,” he writes. “Our business was argument at the level of philosophies, of worldviews, of conflicts that couldn’t be elided and couldn’t be reduced.” It was never much of a business, but some of the sharpest writers of the era heard the calling, at least until they gave in to the temptations of higher word rates, syndication, and TV. Even at its peak, the circulation was this side of 100,000, but under Peretz’s ownership, several of those readers were U.S. presidents.

On the eve of the 2000 election, Peretz was “at the apex of [his] influence.” His friend and former student Al Gore “seemed to be on the verge of the presidency and the New Republic was still in the center of American political discourse.” Fast-forward 10 years. “The invasion of Iraq, which I backed, is a disaster,” he writes. “The financial system that my friends helped build has crashed; my wife and I are divorced; the New Republic is sold after I feared going bust—and here I am in my white suit walking across Harvard Yard, surrounded by students: ‘Harvard, Harvard shame on you, honoring a racist fool.’ The racist fool is, apparently, me.” What happened? The Controversialist is, in part, Peretz’s attempt to answer that question.

The Making of Martin Peretz

Born in 1938, Peretz grew up in the Bronx, just off the Grand Concourse. “My father … was angry all the time,” he writes. “When the storm passed, I would go to my room and read, and my father would leave me alone because he respected learning: that was my out. Fighting was a form, the only form, of bonding for my father.” Learning and fighting are bound up together, for Peretz, a knot that only tightened over time.

Brandeis, a majority-Jewish university “where people went to fisticuffs over ideas,” was his West Point. Peretz went on to Harvard as a 20-year-old graduate student and remained a “permanent fixture” at the school, teaching without ever becoming a full professor, for nearly 50 years. It was in Cambridge, as a volunteer for H. Stuart Hughes’s long-shot 1962 congressional campaign (against both Ted Kennedy and George Cabot Lodge II) that Peretz first joined the activist fray, and soon he was helping Bayard Rustin organize Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington.

Then, in 1967, came two events that left Peretz politically shell-shocked. The first was the Six-Day War, which Israel won at the price of its victimhood. Student groups were suddenly comparing Zionists to Nazis. The second was the National Conference for New Politics, a gathering to unite the New Left against a common enemy, which turned out to be itself. Peretz, who, along with his new wife, Anne, was one of the principal funders of the meeting, walked out twice: a faction of one.

Even at its peak, the circulation was this side of 100,000, but under Martin Peretz’s ownership, several of those readers were U.S. presidents.

In 1974, at Anne’s suggestion—and with her Singer Sewing Machine inheritance—Peretz bought The New Republic for $380,000. Founded in 1914, the magazine had burned brightly in its early years, but by that point, it wasn’t generating much heat. Peretz writes that his “first act was to fire the old guard or provoke them into quitting.” With that accomplished, he hired Kinsley, his former student, to edit the columns and features, and Leon Wieseltier to oversee the essays and reviews. Together, they set about “pissing off the right people.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, T.N.R. “set the agenda,” and that’s according to a competitor. It was loved and feared in roughly equal measure, and when it stumbled, the Schadenfreude could be felt throughout the Beltway. In some circles, the infamous “Race, Genes & I.Q.” excerpt from Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s 1994 book, The Bell Curve, and “No Exit,” Betsy McCaughey’s error-filled attack on the Clinton health-care plan, are still talked about.

Yet few seem to recall that some of the fiercest and most persuasive criticism of these articles came from within T.N.R.’s pages. For his part, Peretz believes he was right to have opposed the Clinton health-care plan but concedes that he’s “not proud” of McCaughey’s piece. He grants that excerpting The Bell Curve hurt his reputation, but says he “would do it again.” (Given that The Bell Curve and The Controversialist share a publisher in Adam Bellow, one might conclude that Peretz is being diplomatic. But why start now?)

Some pieces, by design, left a bigger impression than others, but the fact is that The New Republic published a range of perspectives on almost every subject of consequence—except Israel. “They thought it was my obsession,” Peretz writes, “and they were right about that. Zionism was the one thing I absolutely would not compromise on, the one way I unilaterally exercised my ownership prerogative.” (It turns out that even Peretz has his limits. This past February, he co-authored an op-ed for The Washington Post titled, We are liberal American Zionists. We stand with Israel’s protesters.)

But just like George Lois’s slogan for Levy’s real Jewish rye, you didn’t have to be a Zionist to love Marty Peretz’s New Republic. I became a subscriber in my mid-20s, during what turned out to be the twilight of the magazine’s second golden age, and I got far more than my money’s worth. To understand why some people are, in spite of everything, still such partisans of the Peretz years, read Martha Nussbaum on the cult of Judith Butler (“The Professor of Parody”), Enrique Krauze on Chavismo (“The Shah of Venezuela”), Paul Berman’s grand unified theory of left-wing political violence (“The Prisoner Intellectuals”), or the 18 critiques of “Race, Genes & I.Q.”

The New Republic was not alone in supporting the Iraq war. That, for many readers, was the problem. Once fearlessly, even recklessly independent, the magazine had lumbered along with the rest of the legacy media into a decade-long quagmire. Its influence was receding, and “as things slipped away,” Peretz “got more distant, harsher.” In 2009, his 42-year marriage to Anne ended in divorce, leaving him “alone. Really alone.” (The fact that Peretz is gay probably didn’t help.) Alienated and opinionated, he needed an outlet and decided to give blogging a try. He called his New Republic blog “The Spine,” which, he says, “gives you an idea of how I saw myself right then.”

A few T.N.R. veterans, namely Andrew Sullivan and Mickey Kaus, became masters of the new form. Peretz was not among them. “Oftentimes,” he writes, “I wasn’t making arguments, I was making noise, less interested in persuading people and more in throwing punches.” On September 4, 2010, he threw one punch too many, writing, “But, frankly, Muslim life is cheap, most notably to Muslims.... So, yes, I wonder whether I need honor these people and pretend that they are worthy of the privileges of the First Amendment which I have in my gut the sense that they will abuse.” Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times condemned the post, and other columnists followed. Peretz responded with a qualified apology that satisfied no one. In 2012, he sold his share in The New Republic to one of Mark Zuckerberg’s college roommates. (Win McCormack, a co-founder of Mother Jones magazine, bought it in 2016.)

The first imperative when writing a memoir is to be honest, and Peretz certainly tells it like he sees it. Although the better part of his life was devoted to politics, The Controversialist is entirely free of political considerations. Agree or disagree, you know where Peretz stands on everything and everyone, especially himself. He has grudges, and he has regrets. But if he had quieted his instincts to coolly consider his options, if he had performed a risk-benefit analysis at every crossroads, if he had done anything differently at all at any point along the way, well, then, he wouldn’t be Marty Peretz.

The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone, Left Right and Center, by Martin Peretz, is out now

Ash Carter is a Deputy Editor at AIR MAIL and a co-author of Life Isn’t Everything: Mike Nichols as Remembered by 150 of His Closest Friends