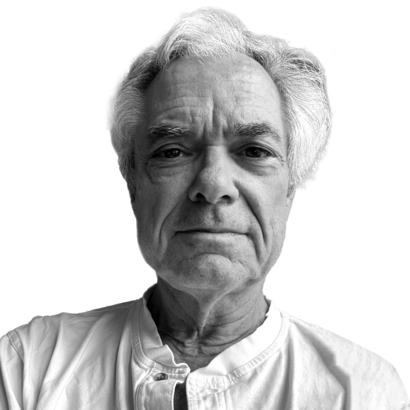

Dealing with Lawrence Schiller—improbable, inescapable, impossible to define—can be exhausting, as can writing about him. Depleted one night by unending battling and bargaining while profiling him for Vanity Fair in 1996 following the O. J. Simpson trial, in which he’d played a crucial behind-the-scenes role, I sought refuge in cable TV, watching Muhammad Ali refight Joe Frazier in the notorious “Thrilla in Manila” from 21 years earlier. And there at ringside, his good eye peering through his Rolleiflex, was Schiller. When the memoir of Schiller’s I worked on—possible titles included “The Original Zelig” and “The Lies I Told to Get the Truth”—failed to sell, I was disappointed, but also relieved. I still think, though, that passing on the project constituted myopia, if not malpractice, on the part of book publishing.

For no one had ever lived a life like Schiller, who, as a photographer, book packager, filmmaker, and indefatigable operator, leapfrogged from celebrity to celebrity, saga to saga, scandal to scandal, attaching himself to everyone from Lee Harvey Oswald to Marilyn Monroe to Charles Manson to Patty Hearst to Norman Mailer, with whom he had—“enjoyed” wouldn’t be quite right—the most bizarre and productive literary collaboration ever.