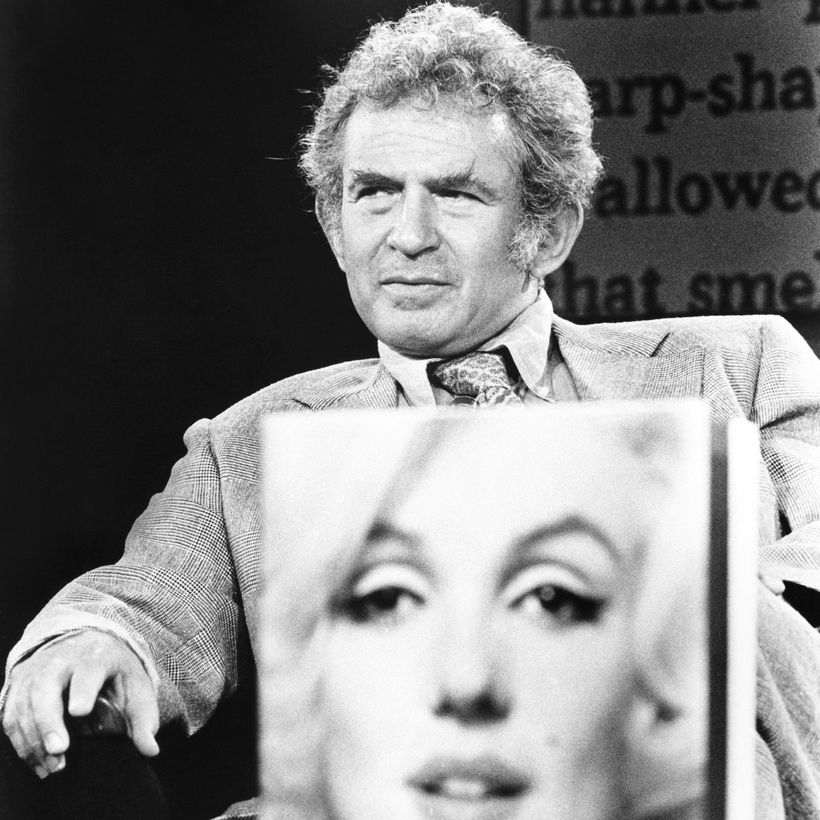

An essentially illiterate man, someone who’d never read a novel or even a newspaper article all the way through without difficulty, helps resurrect and then extend the career of one of America’s foremost novelists. More than that, he becomes one of that novelist’s closest friends, caring for him until the day he dies, and then tends tirelessly to his legacy. Together, they form one of literature’s oddest couples and surely its most improbable and successful collaborations. On their first joint venture, they end up loathing one another and vowing never to work together again. But they—Norman Mailer and Lawrence Schiller—simply can’t stay apart, and only a few years later they’re back at it, with a book that wins the Pulitzer Prize: The Executioner’s Song.

Mailer I never managed to meet. But Schiller I’ve known for almost 30 years, going back to the O. J. Simpson trial. A couple of years ago, I was shocked when publishers passed on his proposed memoir, which I was helping him write; after all, for most of his nearly 90 picaresque years, years of nonstop energy, ingenuity, guile, and hustle, Schiller has been able to sell just about anything. True, his life story might have been a fact-checker’s, and maybe a lawyer’s, worst nightmare, but in my very subjective judgment at least, it would also have become a classic, for never has there been a life like his, nor—in a time when personalities have flattened, and shadows shortened—will there ever be again.