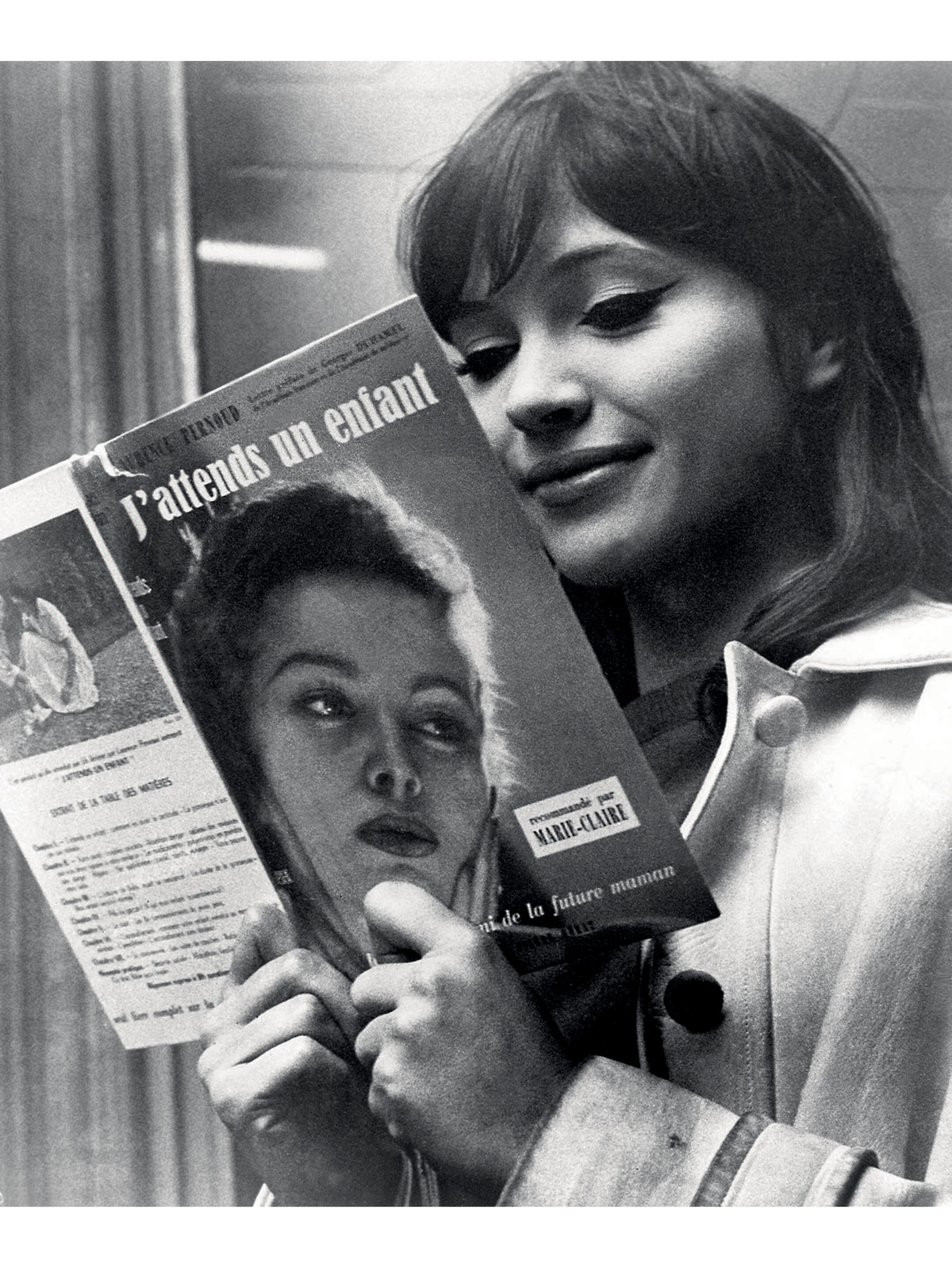

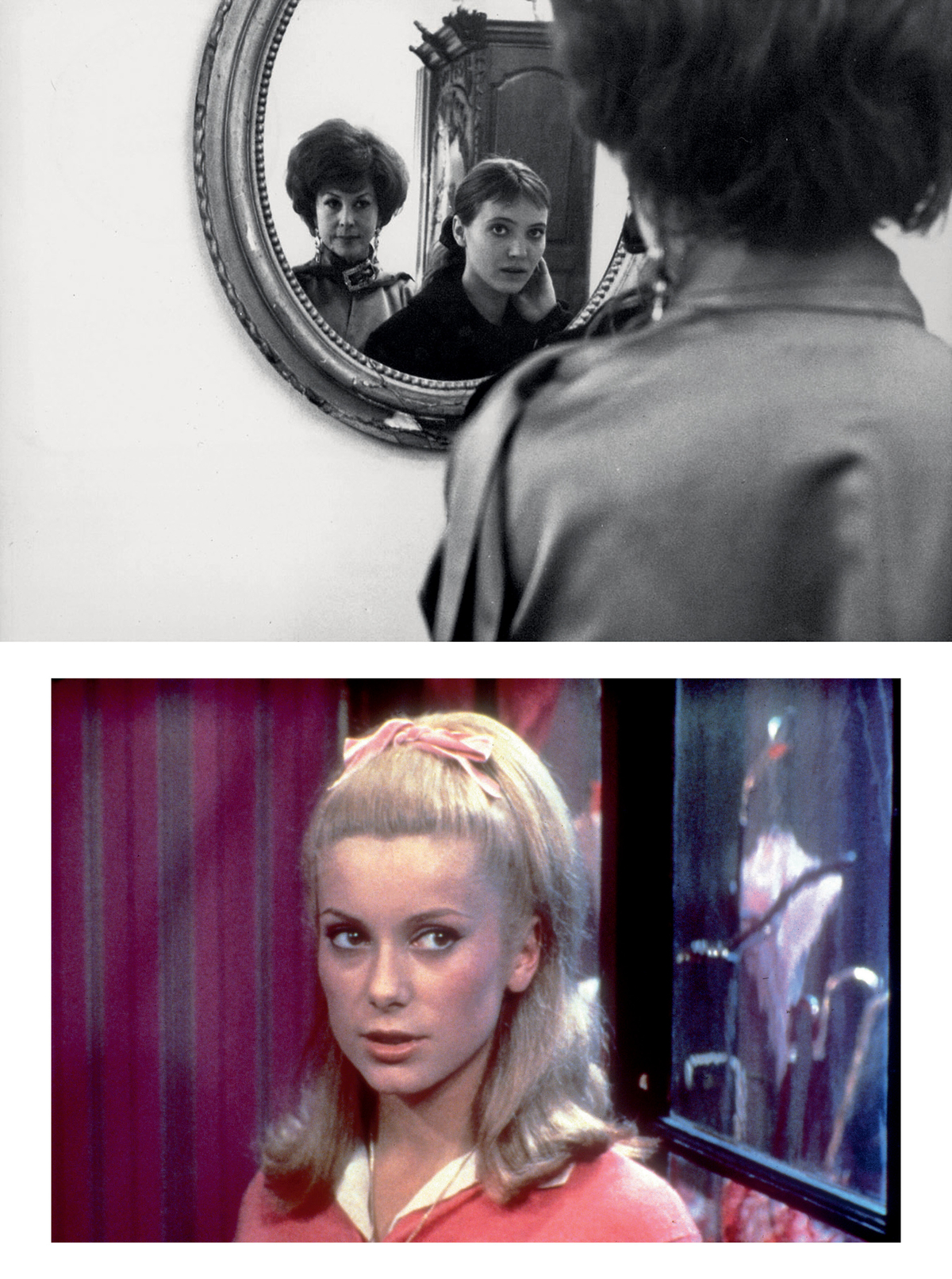

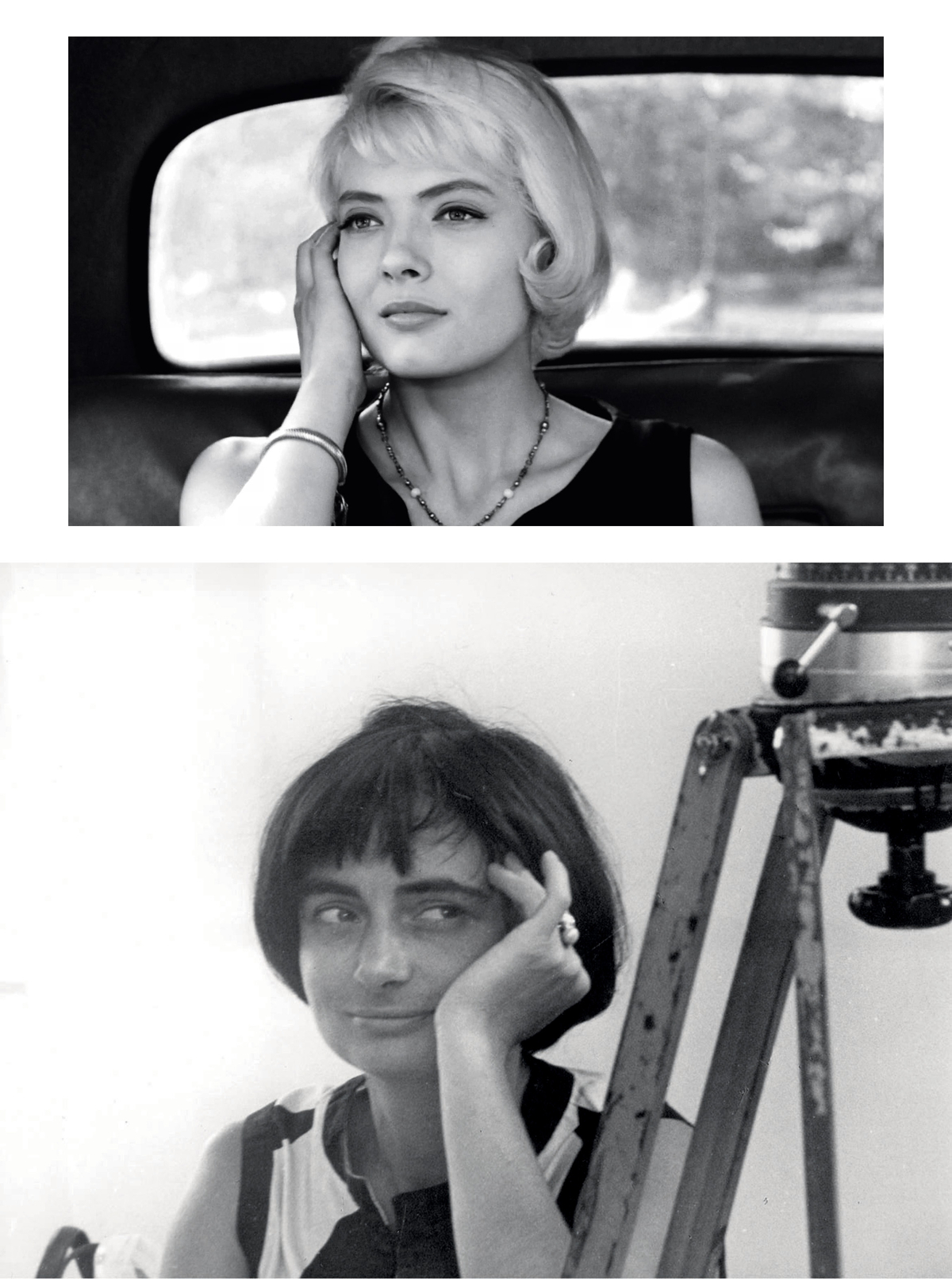

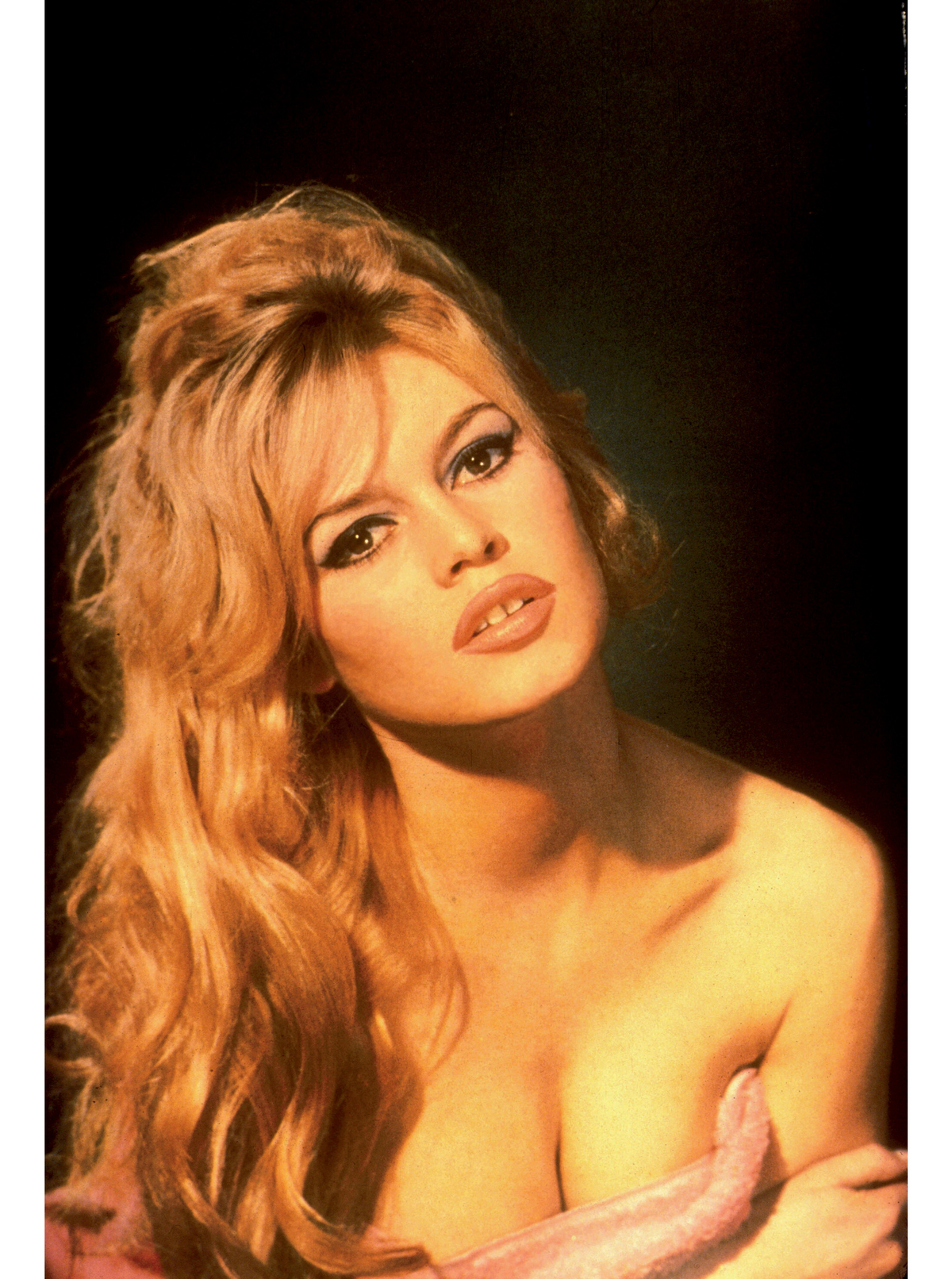

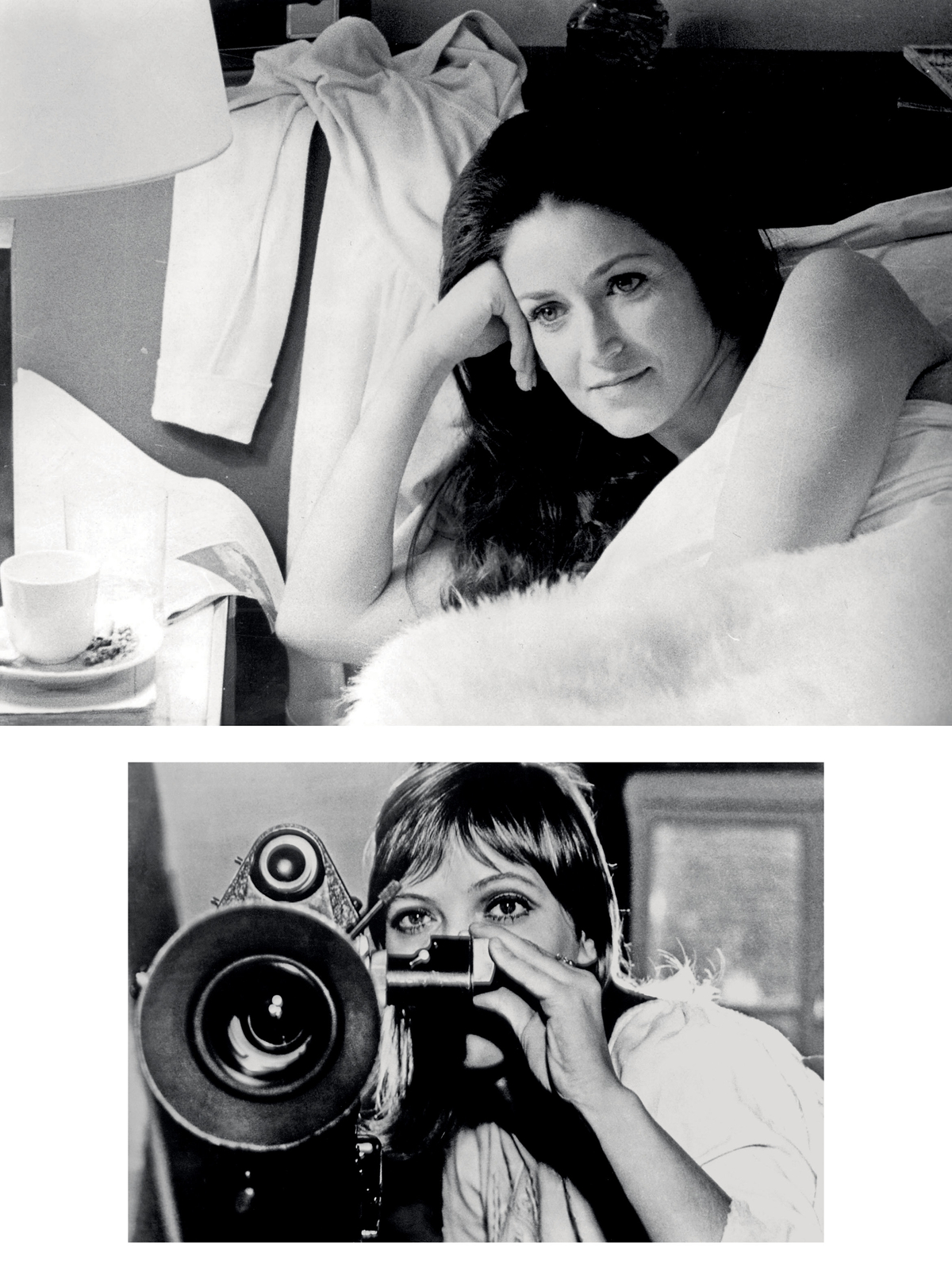

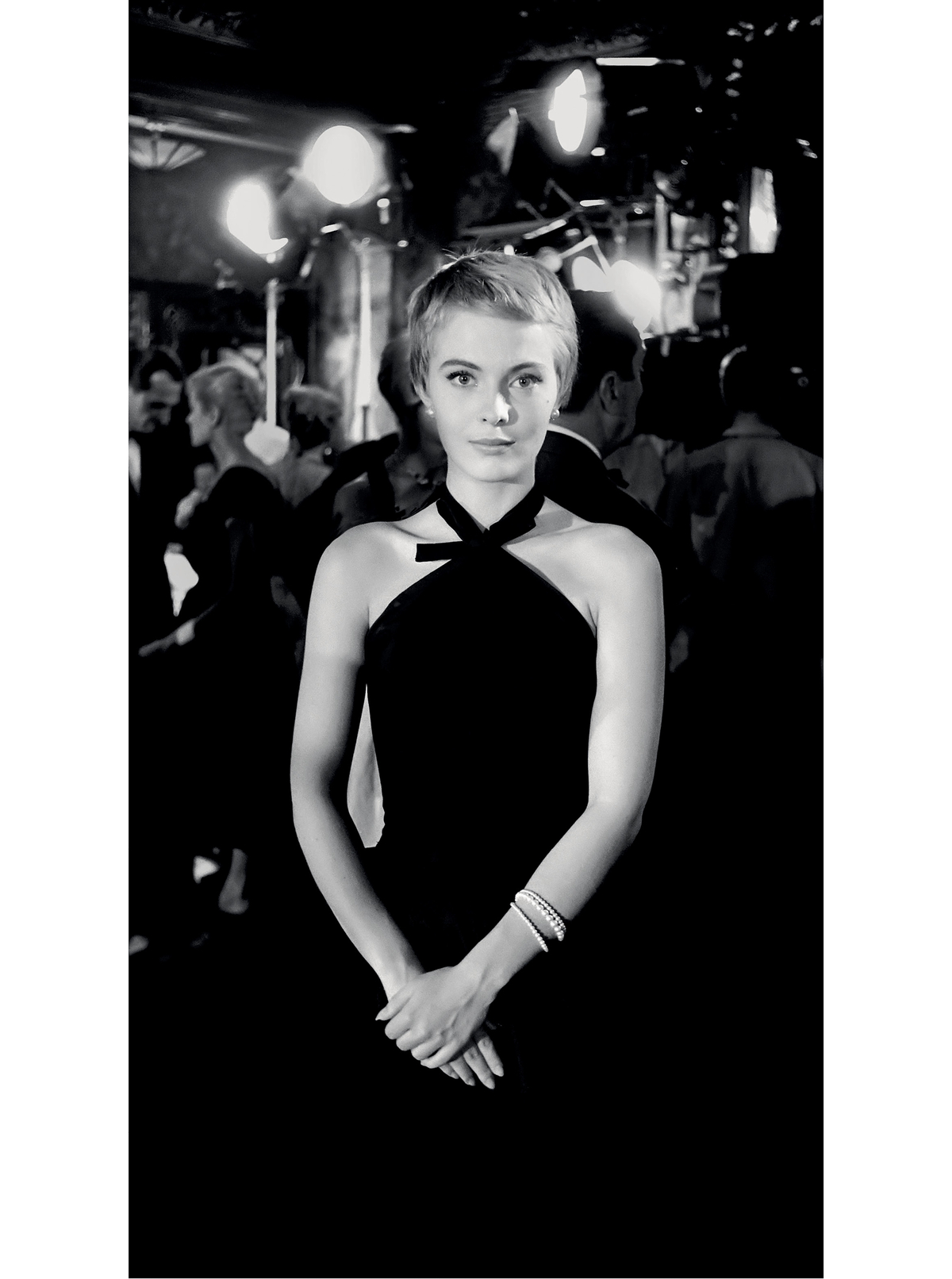

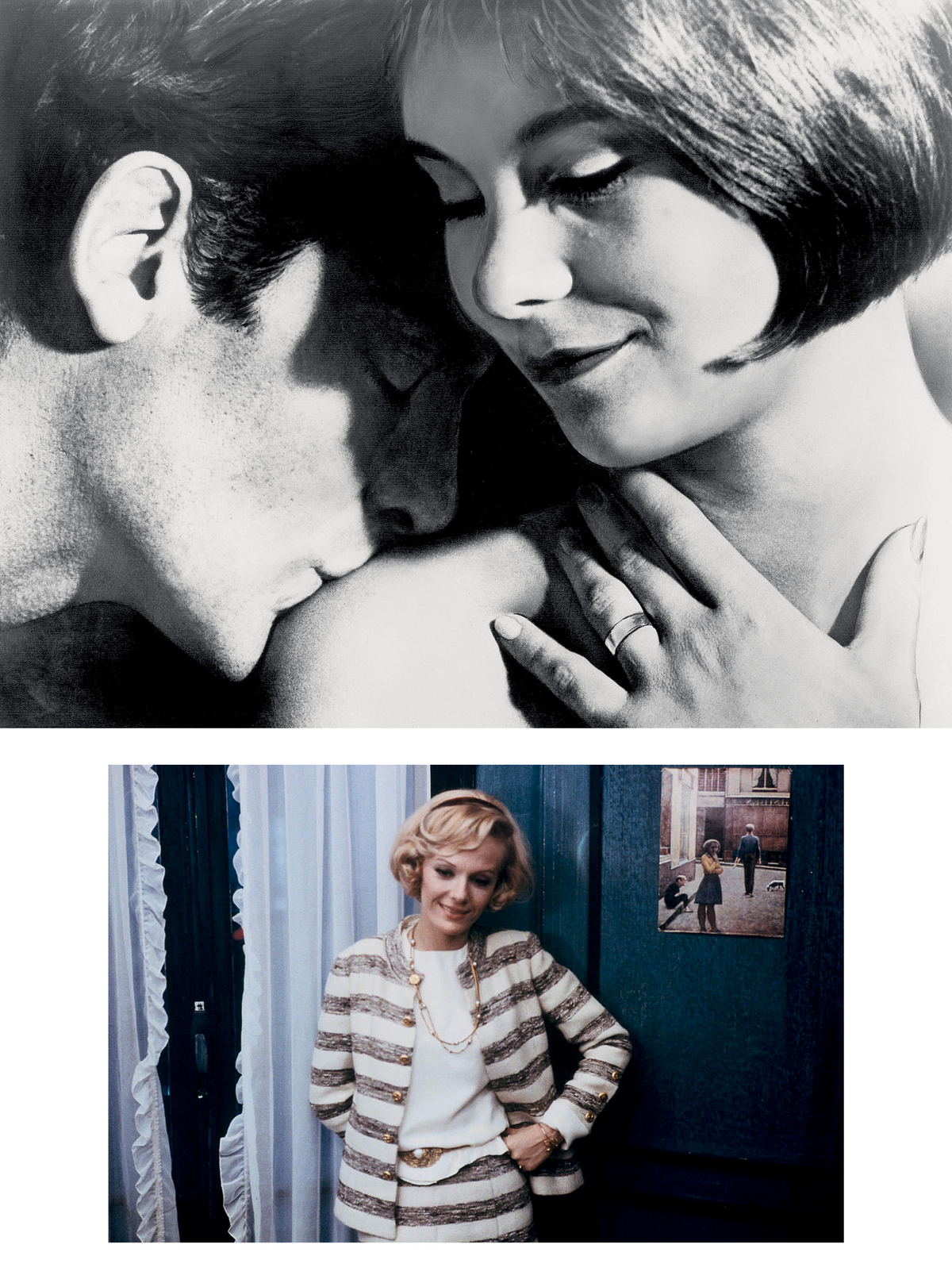

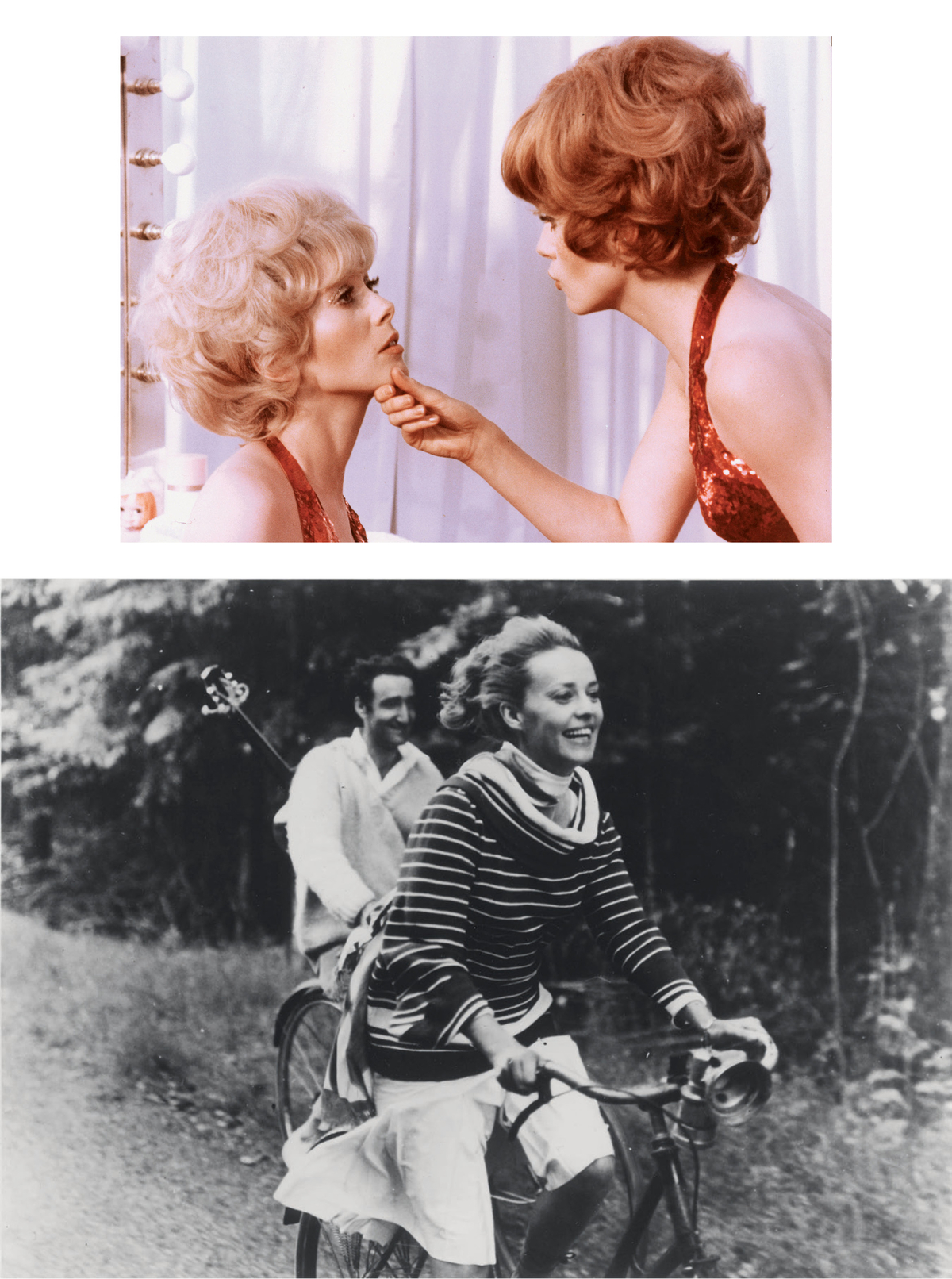

If you’re a fan of the 1960 New Wave classic Breathless and loved Richard Linklater’s 2025 Nouvelle Vague, in which Zoey Deutch plays a young Jean Seberg during the filming of Breathless, you will need to find a place on your coffee table for Ericka Knudson’s Nouvelles Femmes. God knows Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Demy, and Jacques Rivette have gotten their fair share of recognition; this book is a much-deserved nod to the women of the French New Wave.

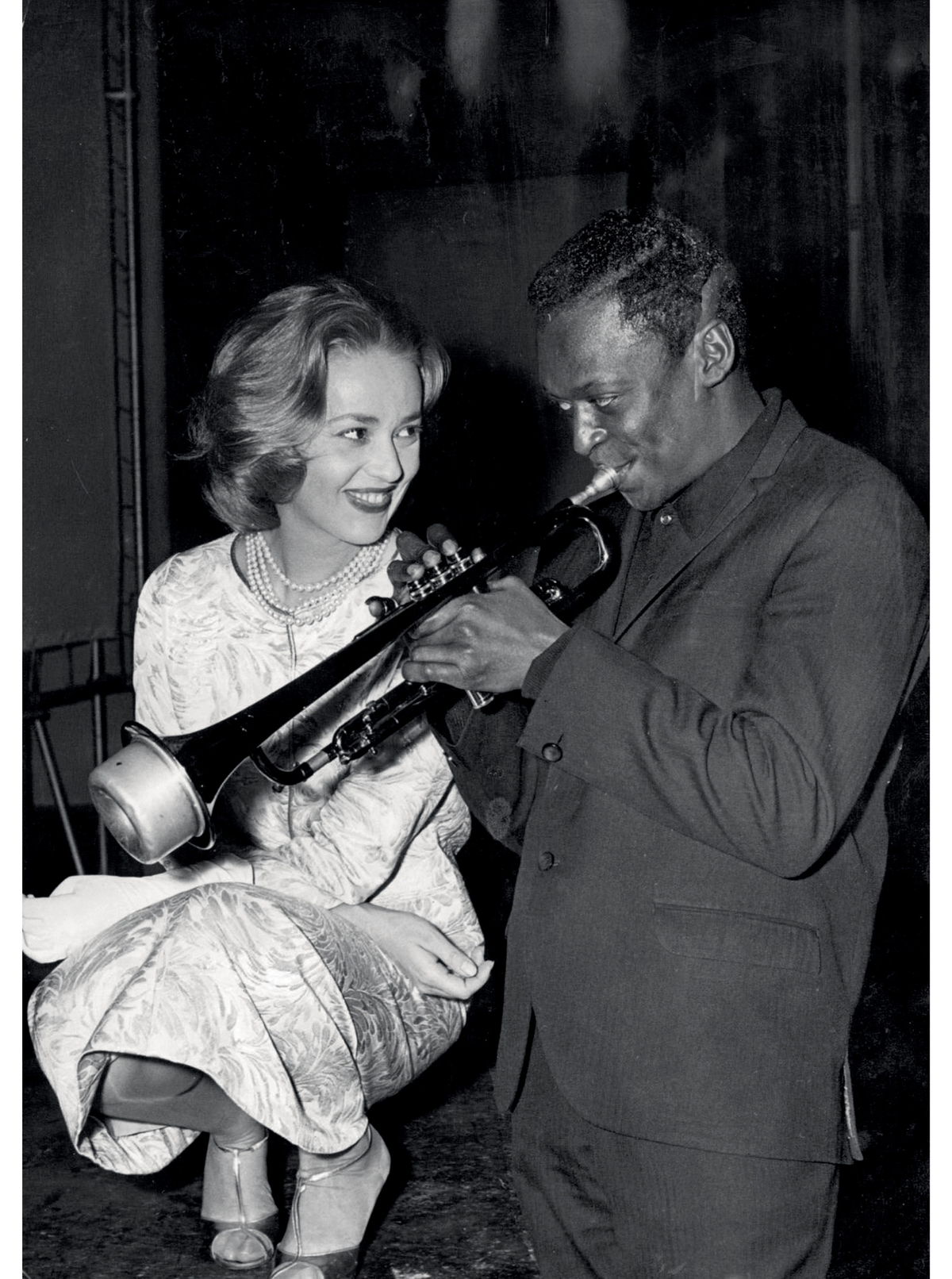

Embracing one of the most influential movements in film history, the book explains its stars in the context of postwar France, a time when nightlife and alcohol were ways to forget the recent German occupation. This shift toward rebellious hedonism was captured in Bonjour Tristesse, the debut novel of 18-year-old Françoise Sagan. Her pampered protagonist, the 17-year-old Cecile, is raised in a “bobo”—bohemian bourgeois—environment that rejects formality and responsibility for more careless fun. In Otto Preminger’s 1958 film adaptation, Cecile was brought to life by none other than Seberg. Indeed, Sagan’s novel, and the “Saganism” it inspired, added its own spin to New Wave sensibility: “Fast love, fast cars, and Scotch distract from a deeper malaise.”