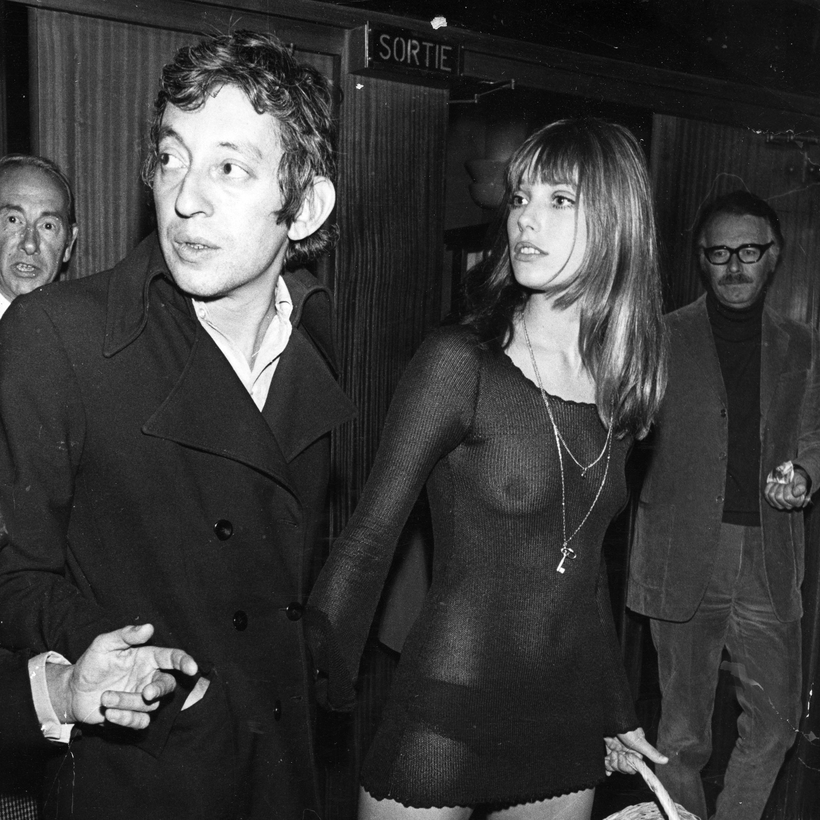

Marisa Meltzer’s slim biography of the British woman named Jane who became the French bag named Birkin is fittingly titled It Girl.

It is subtitled The Life and Legacy of Jane Birkin. The absurd arc of her public destiny reflects our unstoppable drift from culture to commerce. A woman whose erotic sigh-singing became a global soundtrack in 1969 is better known as the supreme trophy handbag.