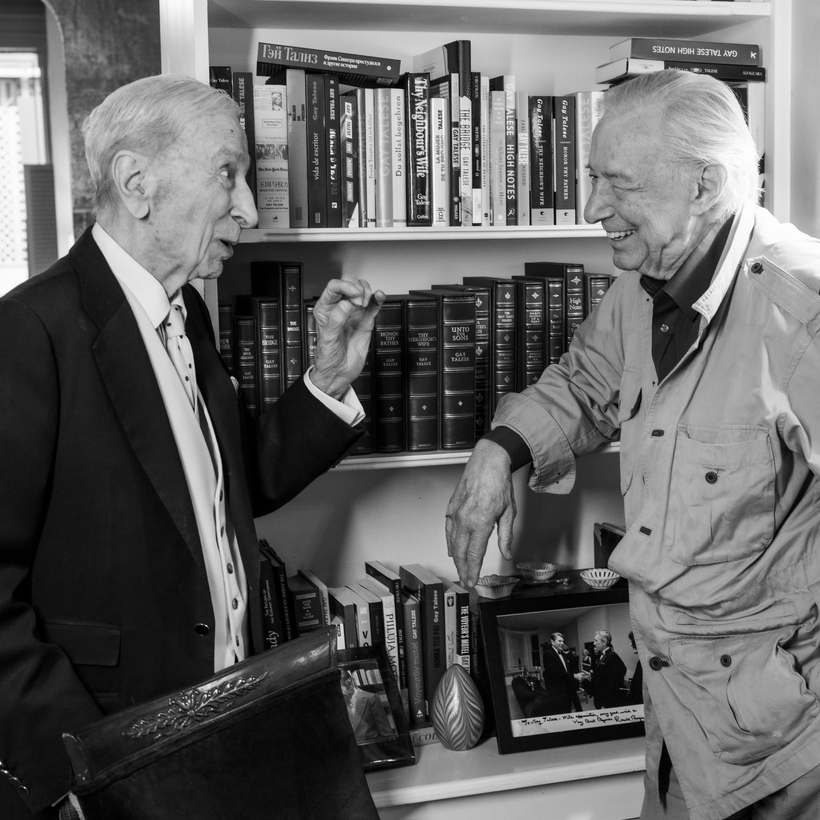

Sixty years ago this fall, the 33-year-old Gay Talese flew from New York to Los Angeles to report a cover story for Esquire, the “It” magazine of the 1960s. His quarry was Frank Sinatra, the reigning entertainment icon of the 20th century, then on the verge of turning the irksome age of 50. To complicate matters, Talese didn’t feel like writing about Sinatra, preferring non-celebrity subjects, while Sinatra, hampered by post-nasal drip, didn’t feel like talking to Talese. (“Which turned out to be a good thing,” Talese says.)

The resulting game of cat and mouse produced what is arguably the greatest magazine profile in the annals of journalism, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” which ran in Esquire’s April 1966 issue.