One day in the late 1970s, when he was at the peak of his fame, Burt Reynolds took a short drive with a couple of friends, the character actors Charles Nelson Reilly and Dom DeLuise. Starting from Italian Farms, his 160-acre ranch outside Jupiter, Florida, Reynolds stopped his Cadillac on Indiantown Road, a single unpaved lane near a truck stop on U.S. Highway 1, and announced that he was going to build a theater on that very spot.

Now home to Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and about half the PGA Tour, Jupiter was at the time “a sleepy little hamlet with dirt roads,” says actor Gareth Williams, who grew up nearby. “I used to call it ‘Mayberry on the beach.’”

Reynolds, a native of nearby Riviera Beach, had long dreamed of opening a playhouse in the area. DeLuise and Reilly thought he was crazy, but in May 1978, Reynolds broke ground on the Burt Reynolds Dinner Theater, a 400-seat playhouse, restaurant, and bar complex that cost $2 million. The idea was to bring high-level productions to a community where that kind of thing didn’t exist.

“I want a theater for people who haven’t seen live theater—at prices they can pay,” Reynolds told a reporter.

Equally important was creating a place where Reynolds could bring his showbiz pals to hang out, take risks on stage, and refine their craft before a live audience. And many came, including Elliott Gould, Charles Durning, Marsha Mason, Fannie Flagg, Abe Vigoda, Catherine “Daisy Duke” Bach, Robert Urich, Stockard Channing, Marilu Henner, Dick Cavett, and Alice Ghostley, the blundering Esmeralda on Bewitched, who possessed, according to Reynolds, “the best legs in Hollywood.”

“Burt pulled people towards him. You wanted to be near him,” says Henner. “It was this incredible place to experiment, and there was a collective agreement to succeed, because everybody loved him and loved the place. You wanted to be your best.”

Martin Sheen, who starred in Mr. Roberts and One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest at the theater, said that there were only two people who could get him back onstage. One was Public Theater founder Joseph Papp. The other was Reynolds.

Long before tourists and hedge-fund managers were paying top dollar to see George Clooney, Denzel Washington, and Bill Burr on Broadway, it was the eternally grinning Smokey and the Bandit star who understood the value of putting movie and television stars onstage.

Opening in January 1979, the theater’s first production was Vanities, starring Reynolds’s girlfriend Sally Field and Tyne Daly, which received positive reviews. The only glitch was the Los Angeles Times’s referring to the theater as “the Burt Reynolds Institute.” “What’s next?” said Reilly. “The Anson Williams Conservatory? The Sonny Bono Academy?” For his part, Reilly preferred to call it “the Miracle at the Truck Stop.”

From 1979 to 1989, the theater put on 116 shows, whose eclectic casting ranged from remarkable to unintentionally bizarre.

Some productions you’d expect to find on Broadway, such as Death of a Salesman, with stage veteran Julie Harris and two-time Oscar nominee Vincent Gardenia; I’m Not Rappaport, with Ossie Davis; and Same Time, Next Year, with Burt playing opposite Carol Burnett. When Reynolds mentioned that show to Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, the box-office phone rang from midnight until four A.M.

Other shows, however, felt like Fantasy Island episodes made for Mystery Science Theater 3000: Jim Nabors and Florence Henderson in The Music Man (one savage review reduced Nabors to tears); Bernie Kopell (Doc from The Love Boat) and Karen Valentine in Social Security. Worst of all was the unholy trinity of Norman Fell in Brighton Beach Memoirs, Orson Bean in Harvey, and Stage Struck starring the confetti-tossing Rip Taylor.

There was even a production of The Teahouse of the August Moon with Gedde Watanabe—Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles—taking on Brando’s role from the 1956 film.

But Reynolds understood that even the kitschiest performers could be committed to their craft. Nobody embodied this duality better than the flamboyant Reilly. Best known as a regular panelist on Match Game, or from his role on the supernatural sitcom The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, he was also a gifted teacher who’d studied under Uta Hagen and whose students included Lily Tomlin, Bette Midler, and Liza Minnelli.

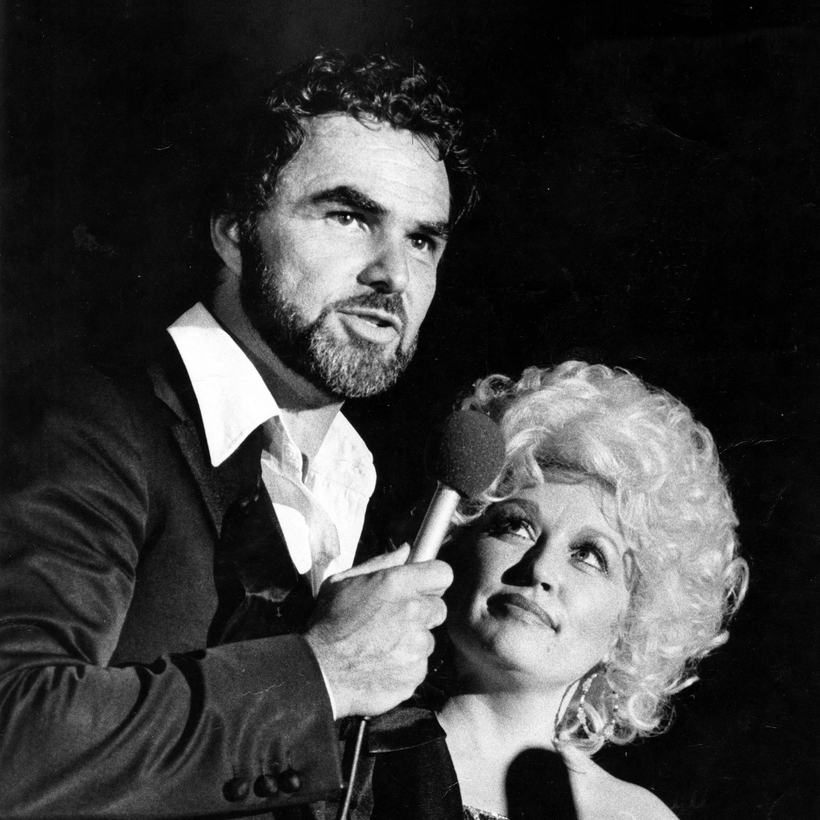

Offstage there were nights you’d look up in Reynolds’s box and see him beside Dolly Parton, Sylvester Stallone, Brian Keith, or John Travolta. One night, Elizabeth Taylor spilled a glass of wine in her lap and threw her pantyhose in the bathroom trash, only to have them retrieved by Reynolds’s longtime employee Elaine Blake Schell, who explained that she “didn’t want to see them framed” in someone’s living room.

Most visitors from Hollywood would speak to the apprentices as a group. Taylor told them about show business. Parton pulled out her guitar to sing during her session. According to actor Ken Kay, “you never knew who was going to show up. Liza Minnelli would just walk into rehearsal. It was nuts.”

When the apprentice Gareth Williams turned 21, his sister, who lived in the wetlands alongside the Loxahatchee River, hosted a little get-together. The party was “old rednecks leaning up against trees” until a stretch limo arrived and Eartha Kitt, who was performing in a musical at the theater, emerged in an elegant black gown. Proceeding to mingle with the swamp folk, Kitt served the ice-cream cake and wound up canoeing down the Loxahatchee with the birthday boy.

“She was down to earth,” Williams recalls, “but she still wore a black gown to a country picnic. I mean, she was still Eartha Kitt.”

Everyone at the theater loved Kitt, as well as Gardenia, Harris, and Sheen. Less popular were Judd Nelson (who was arrested for punching a cop), Kirstie Alley (who did a show with future husband Parker Stevenson), and comedian Shelley Berman, who delivered all his lines directly to the audience, gave lengthy post-show curtain speeches, and required exactly 17 ice cubes in his water.

“And he could tell the difference,” according to actress Peggy Sheffield.

Farrah Fawcett, who co-starred with Dennis Christopher in a 1980 production of Butterflies Are Free, wanted to carve out a career as a “real actress.” Unfortunately, she had terrible stage fright. Her director, DeLuise, tried to lighten the mood by storming into a tech rehearsal wearing a director’s cap and jodhpurs, screaming, “Get the elephants back!!!” into a bullhorn as if he were Cecil B. DeMille in charge of thousands, rather than a three-person play. Everyone laughed, except for Fawcett.

Later, a few gentle notes from DeLuise caused her to burst into tears. When she stopped shaking, Fawcett explained that people had always talked to her about hair and makeup, but never her acting. Then she resumed crying, and, according to Sheffield, “if anyone near Dom started to cry, he lost it. He was practically done for the day, because he’d never recover.”

Fawcett went on to win raves for her performance. “Farrah Can Act!” read one headline.

Many shows were directed by Reilly, Reynolds, and DeLuise, all of whom taught classes as well. Reilly emphasized reality and authenticity, like Hagen. DeLuise’s technique was described as Meisner with A.D.D. Then there was Reynolds, whose philosophy, Sheffield says, can be summed up in a single word: guts. “He wanted you to reach inside and not be afraid to put it all out there.”

And in many ways, that’s what he did by building the theater. At the peak of his career, Reynolds was tangling with the duality of being able to carry a hit movie in his sleep and wanting to create a place where acting, technique, and art were what mattered.

“My passion for directing,” he said, “is so much more than for acting, I suppose, because when you love actors and you love this business so much, there’s only so much that you can do as an actor. If you love it as a director, you can do anything. Cast people that would never be cast. Turn people’s heads around as far as a project they thought was just OK.”

That dream came to an end in 1989, by which point the theater’s stars were more of the Desi Arnaz Jr. caliber. Despite its success over the years, the theater had to average 95% of capacity to be financially viable and only made a profit during 2 of its 10 years. With the venue $4 million in debt, Reynolds shut it down. Today, however, the house that Burt built is back in existence as the Maltz Jupiter Theatre, run by Andrew Kato, who began working there in his teens, when it still belonged to Reynolds.

And if you get down to Jupiter and go to the corner of Indiantown Road, you’ll find the statue that once sat outside the original incarnation, which was cleaned up and restored after it was tracked down at the South Florida Fairgrounds: Reynolds atop a bucking bronco.

Josh Karp is the author of A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever and Orson Welles’s Last Movie: The Making of The Other Side of the Wind