The lasting gift—and raison d’être—of Gerhard Steidl, the pre-eminent publisher of photography books, is not just to catalogue the most recognized pictures by the world’s finest photographers but also to unearth and breathe life into pictures we’ve never seen before. His mission is our reward.

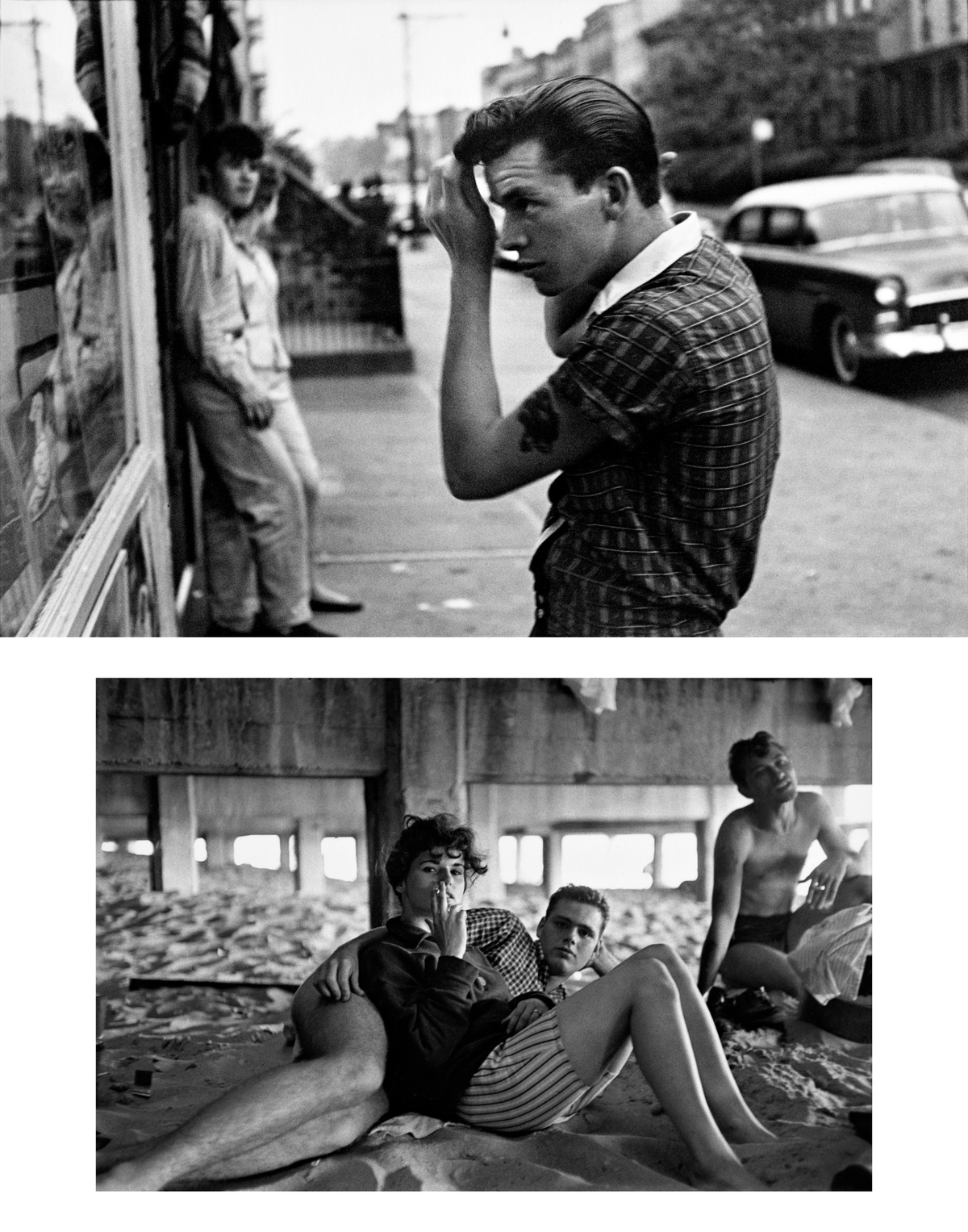

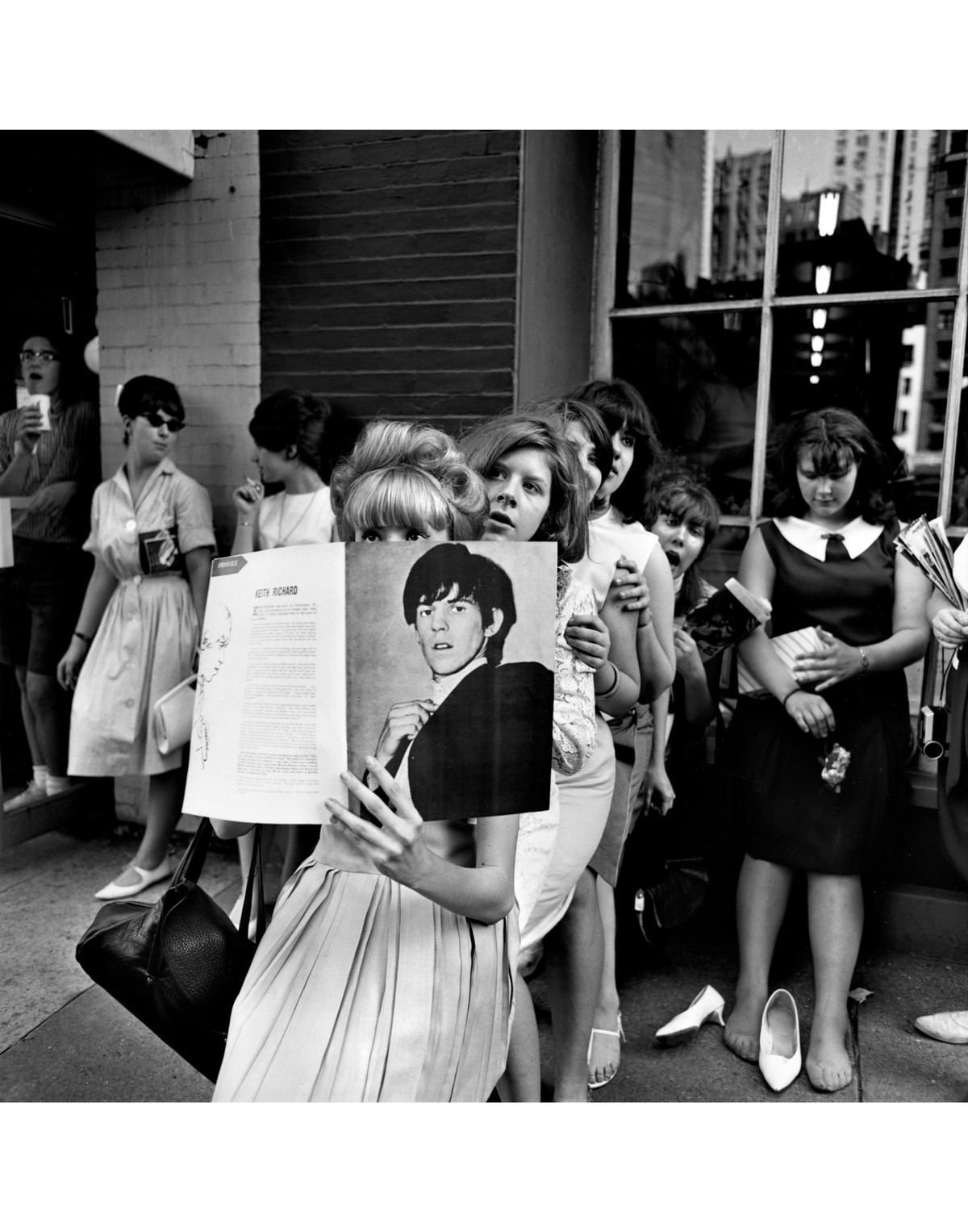

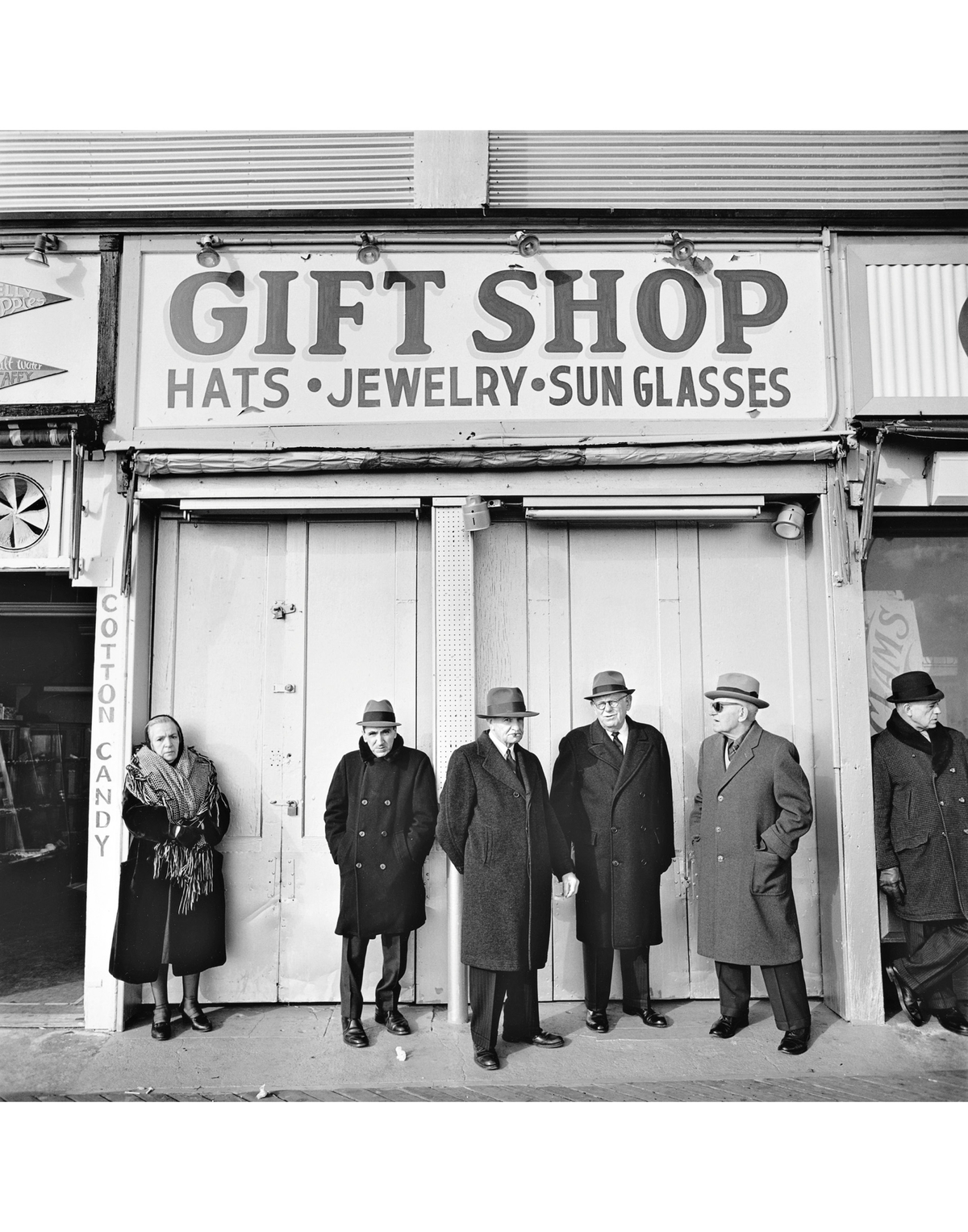

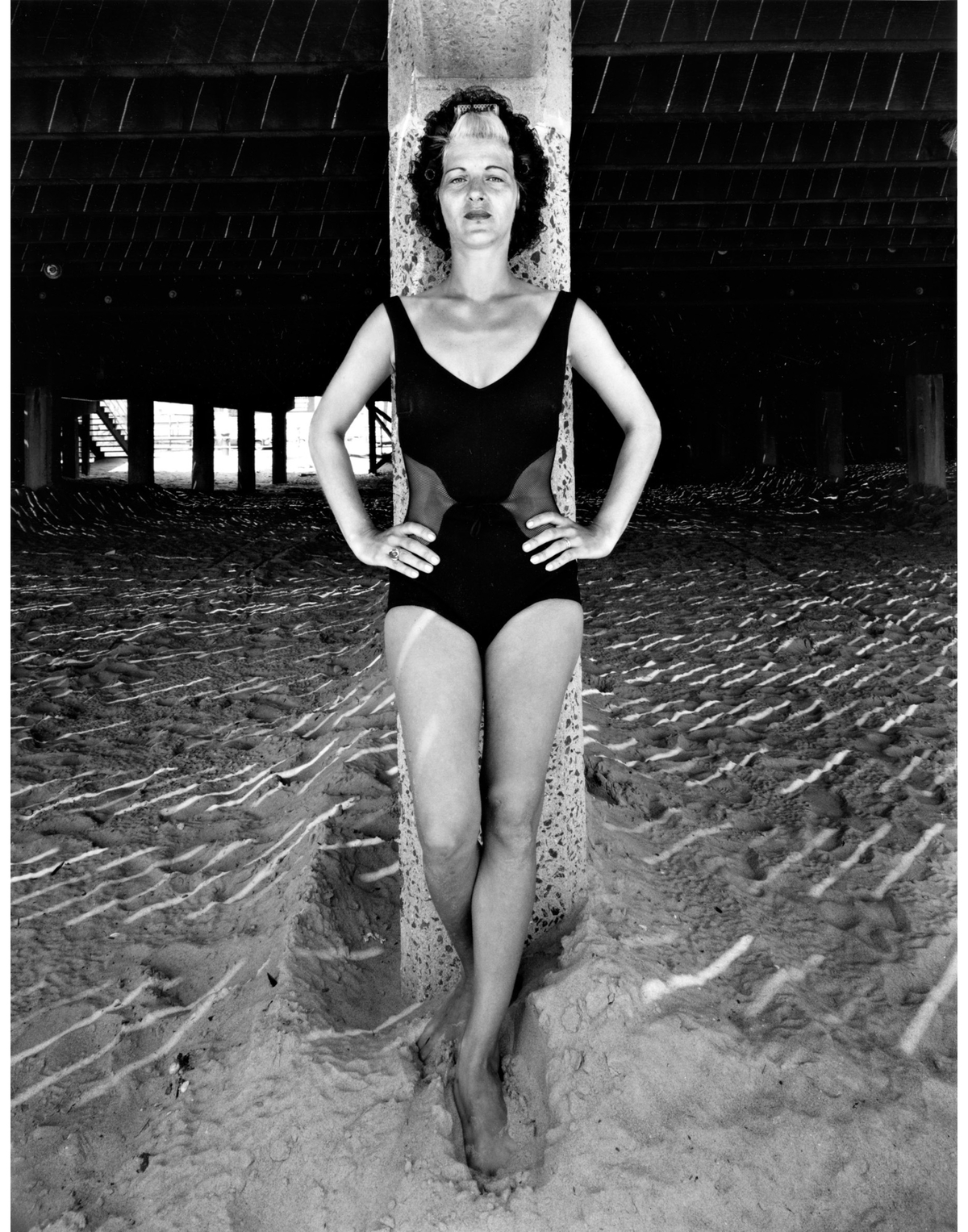

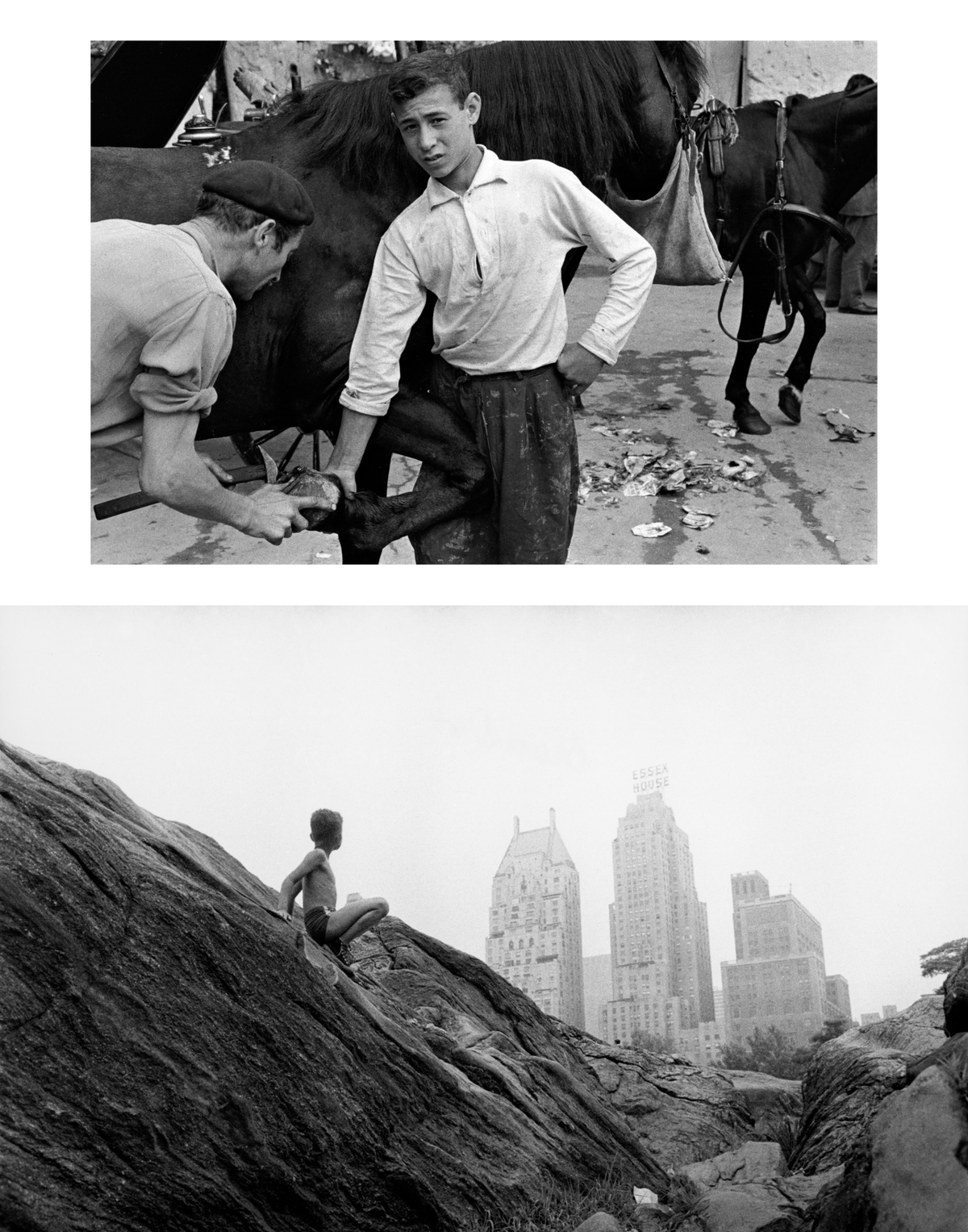

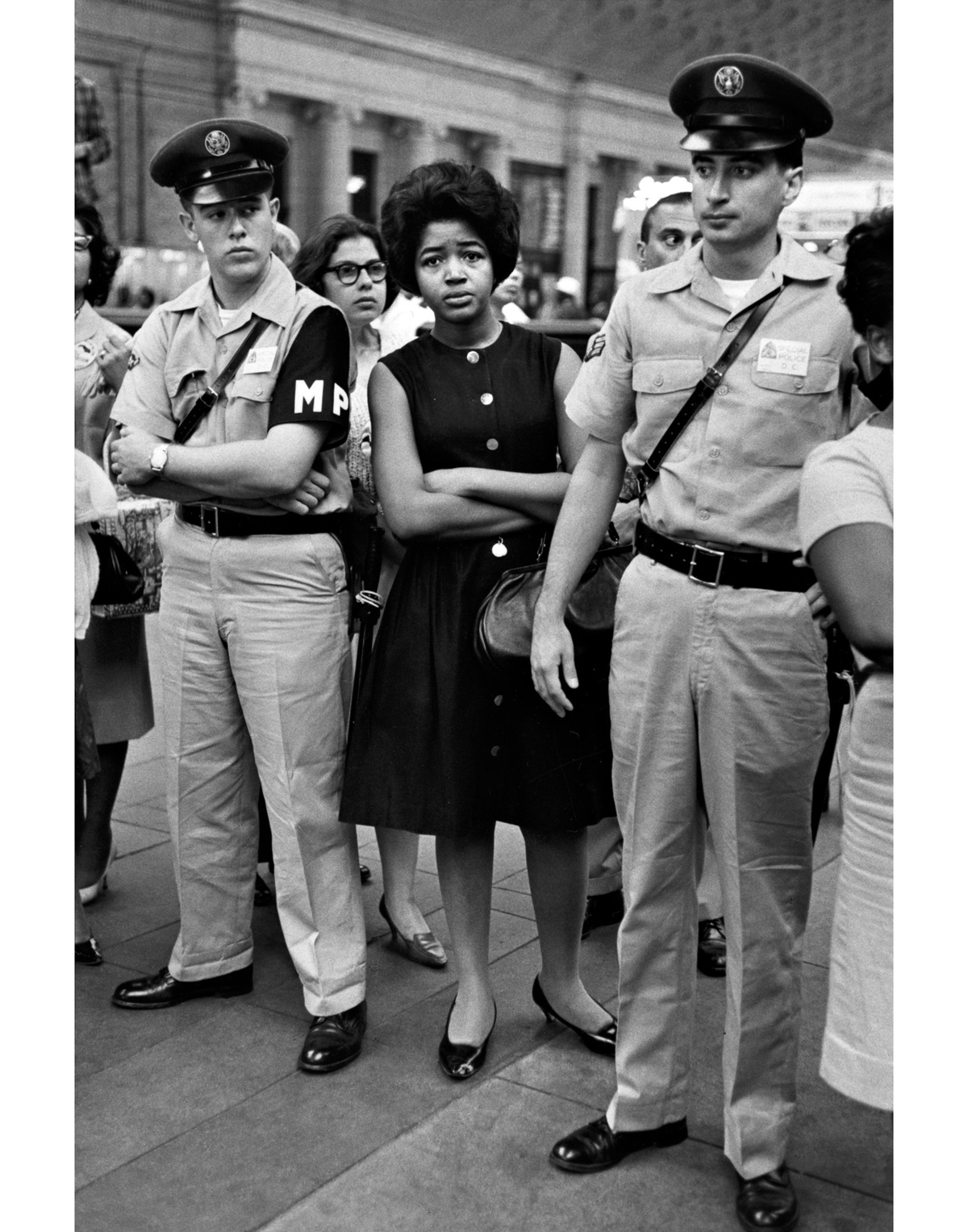

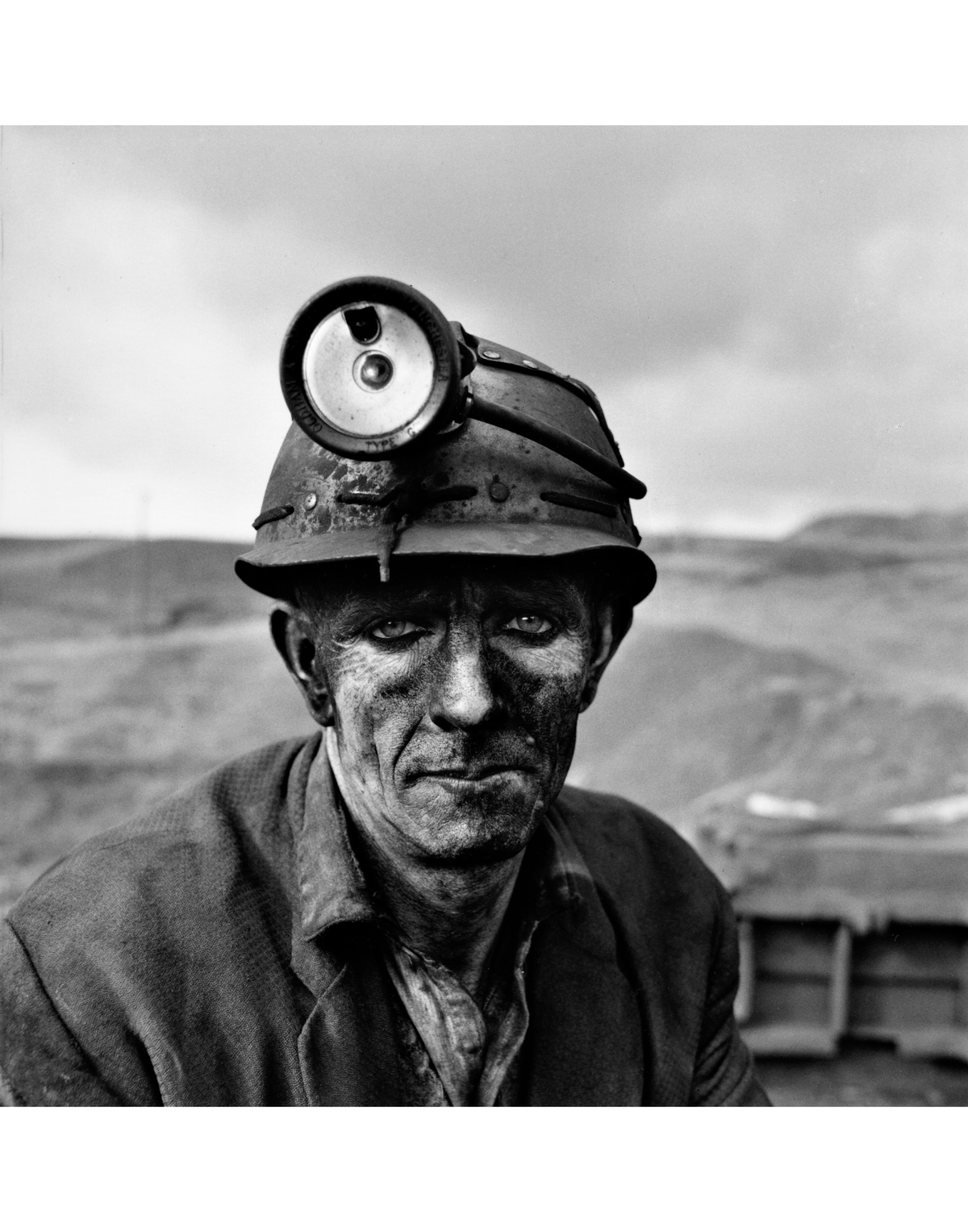

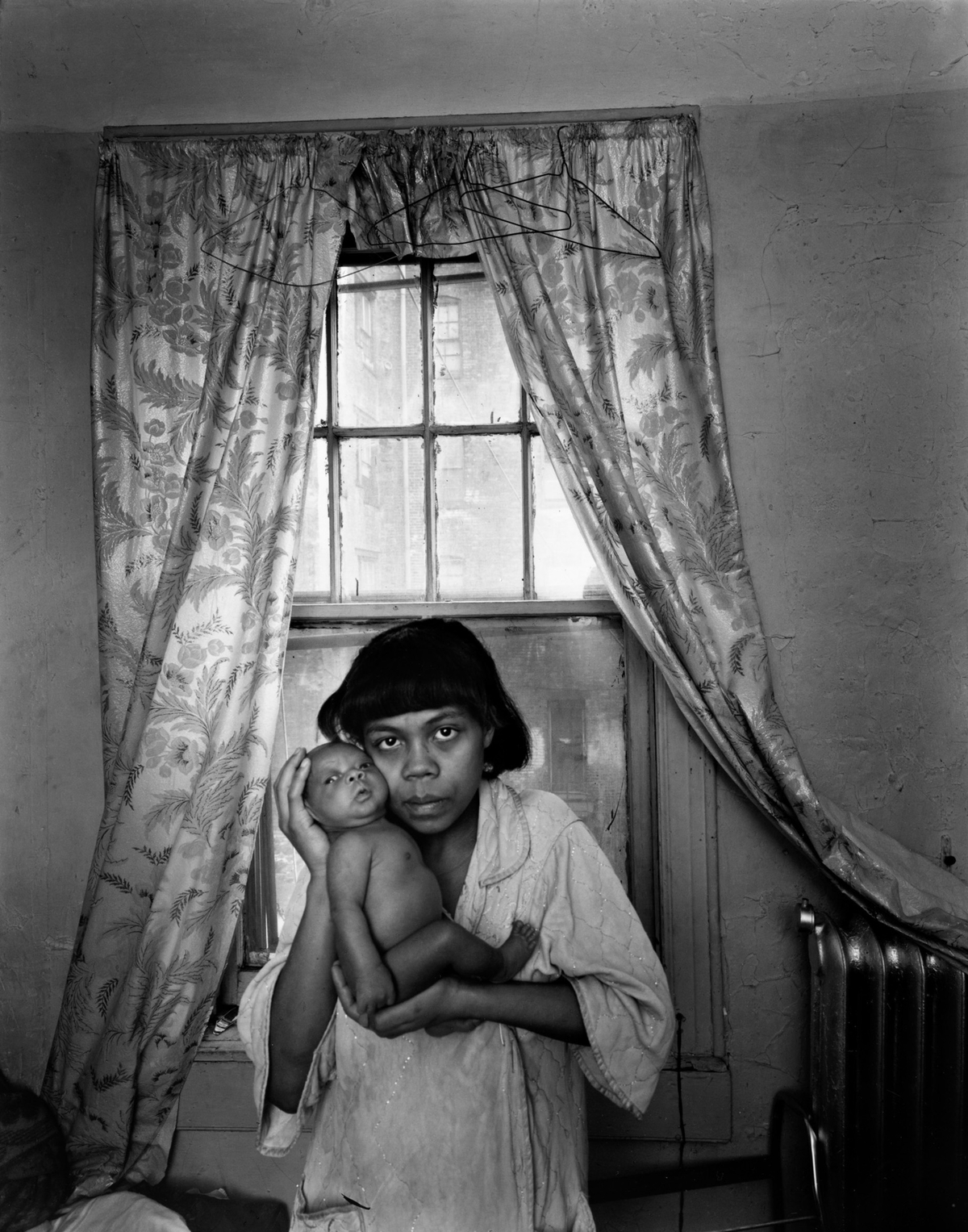

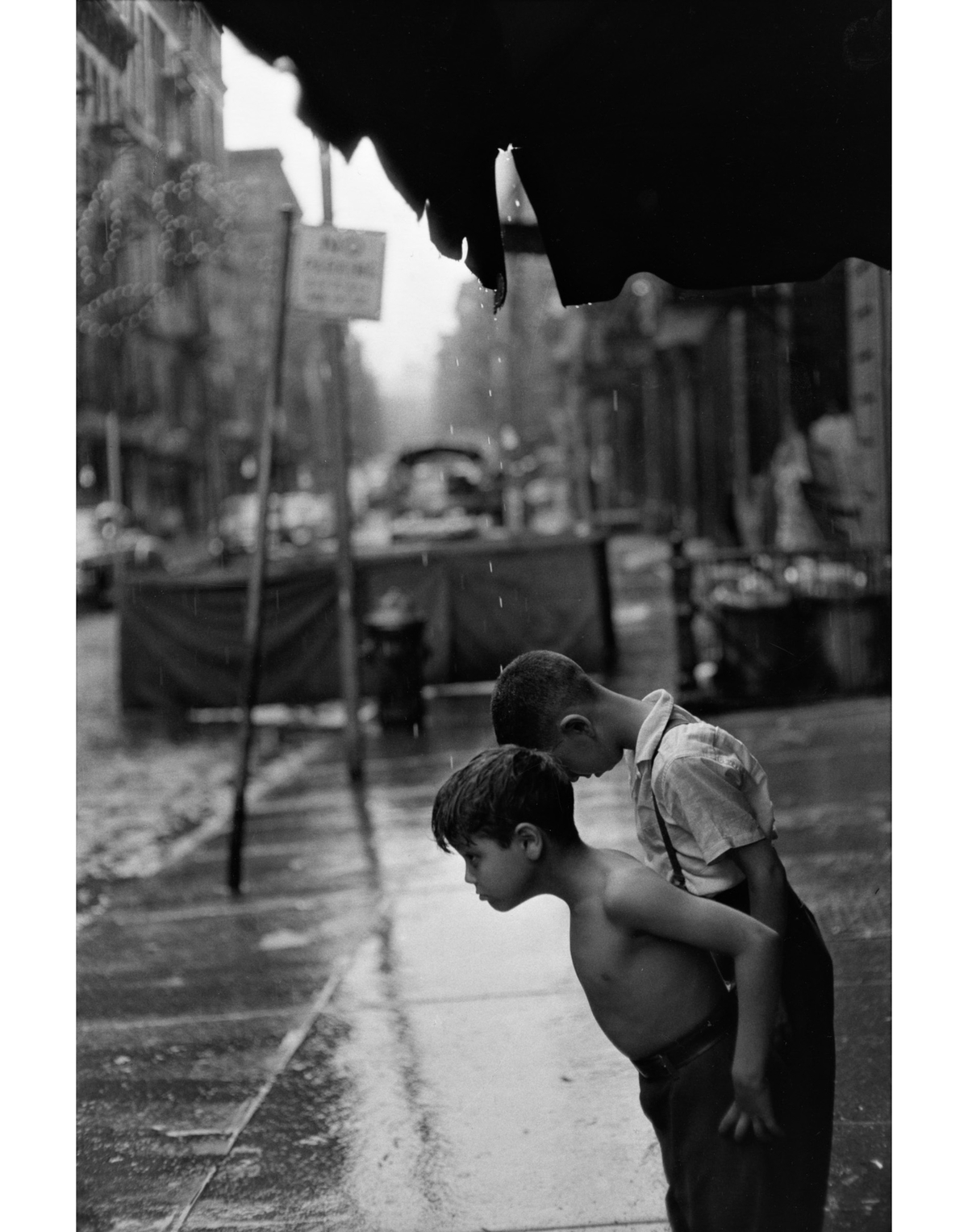

The archives of Bruce Davidson, the longtime Magnum photographer whose magazine work in the U.S. and Europe place him alongside masters such as Lee Friedlander, Mary Ellen Mark, and William Eggleston, have all been meticulously mined by Steidl. Davidson’s photography is marked by daring, curiosity, and emotional directness in his depictions of a group of Brooklyn kids in the 50s (Brooklyn Gang), residents of Spanish Harlem in the late 60s (East 100th Street), and New Yorkers of all stripes commuting later in the decade (Subway), where every trip came laced with nervous energy, menace, and untamed beauty.