When you write about someone in your circle, or close to it—someone who died scandalously, mysteriously, violently—your friends will start to freak out. They will want to know what you have discovered and what you will report.

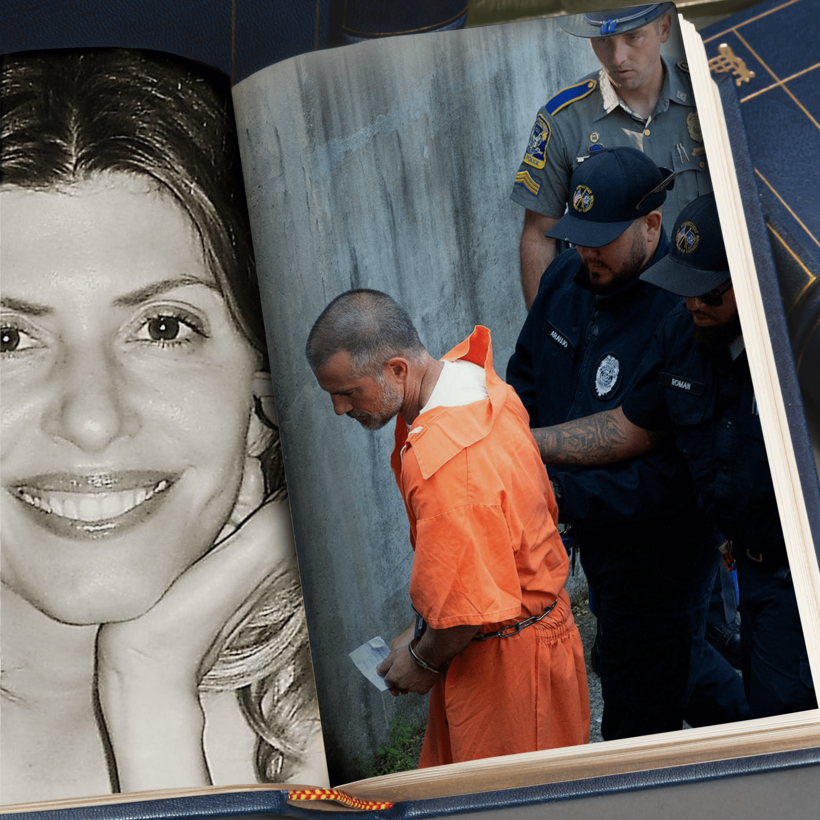

I found this to be the situation with the Jennifer Dulos murder case, which I first wrote about in Air Mail. A woman no longer young but still beautiful, a scion of a powerful New York family—her aunt was Liz Claiborne—a product of Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn and Brown University, a mother of five in the midst of one of the most contentious divorces in the history of Fairfield County, Connecticut (which is to contentious divorce what Las Vegas is to blackjack), drops her kids off at the New Canaan Country School, then vanishes.