No one will ever describe Ron Chernow as a miniaturist. He has written brick-size biographies of John D. Rockefeller, Ulysses S. Grant, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton (read the book, then see the hip-hop version!), plus histories of the Morgan and Warburg banking dynasties.

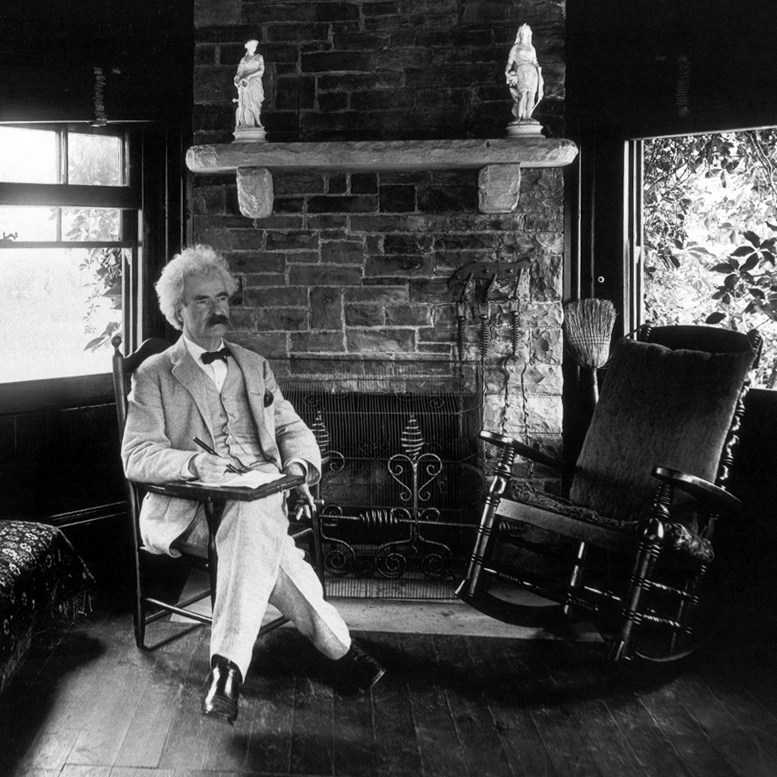

Mark Twain is his latest subject, and the book is an absolute delight to read, written with flair (no surprise there) and keen psychological insight about a surprisingly complicated man prone to depression. Come to think of it, Chernow is a bit of a miniaturist, in the sense that he finds those tiny, telling details that bring alive his sweeping sagas.