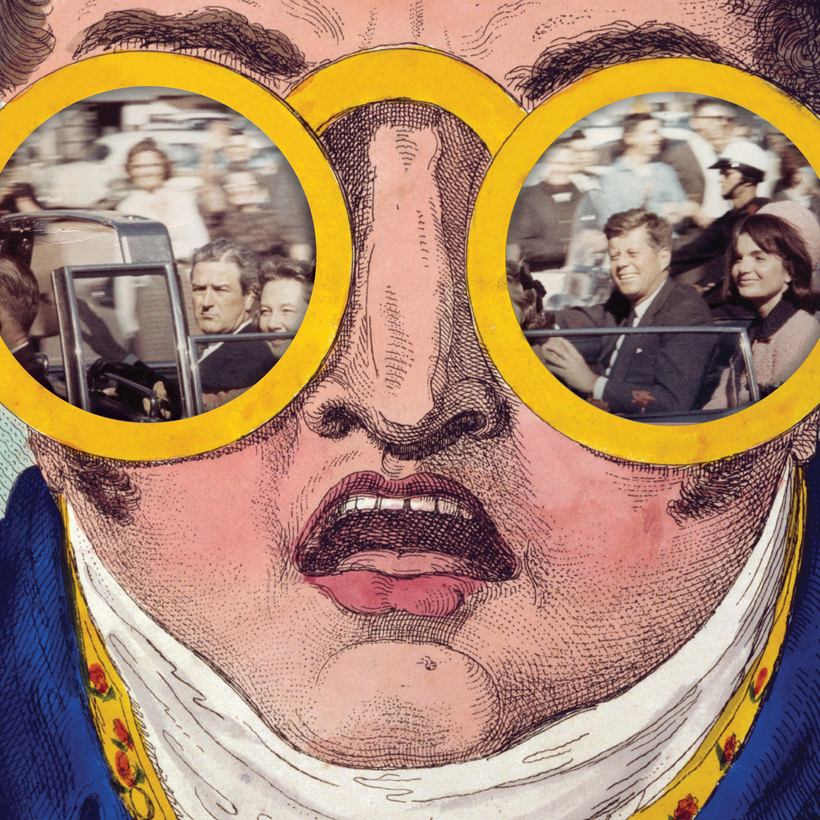

On January 23, three days into his second term, Donald Trump mandated the release of all remaining classified files relating to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Unlike the other 36 executive orders he signed that week, this one was perfectly harmonious with U.S. law—in this case a 1992 bill called the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act—even if it also struck a chord with him personally.

The J.F.K. Act was drawn up and passed just months after the release of Oliver Stone’s JFK, which ended with a Mr. Smith Goes to Washington–style plea for the government to open its unseen archives to the public. As Phil Tinline writes of the $40 million production in his new book, Ghosts of Iron Mountain, “It was the most expensive Freedom of Information request ever made.”