Born in 1914, Saul Steinberg grew up in a Jewish family in Bucharest, Romania, and in 1932 traveled to Milan’s Polytechnic University to study architecture. In 1941, he left. Fascist Italy wanted him out or dead. He spent a year in the Dominican Republic, awaiting U.S. citizenship.

During this time of displacement, The New Yorker published Steinberg’s first drawing. It shows an art student explaining to her teacher that she has indeed painted a centaur—we see that the halves have been reversed and it’s the hind legs that are human. The cartoon got him a contract. Living in a small apartment in Manhattan, Steinberg began to see his work travel far—into Harper’s Bazaar, The New Yorker, and Vogue.

In 1943, William Donovan, chief of the Office of Strategic Services, recruited Steinberg to create anti-Nazi propaganda that would be sprinkled behind enemy lines in Italy and North Africa. He obliged, sketching Hitler with skulls popping out of his head and rendering Mussolini one-eyed and grotesque.

Unlike most illustrators, Steinberg soon crossed over into the art world. In 1946, three of his drawings were part of the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition “Fourteen Americans.” Showing alongside him? Artists such as Arshile Gorky and Robert Motherwell. By the time Steinberg died, in 1999, he’d had solo shows in museums around the world as well as at Galerie Maeght, in Paris, and Betty Parsons, in New York.

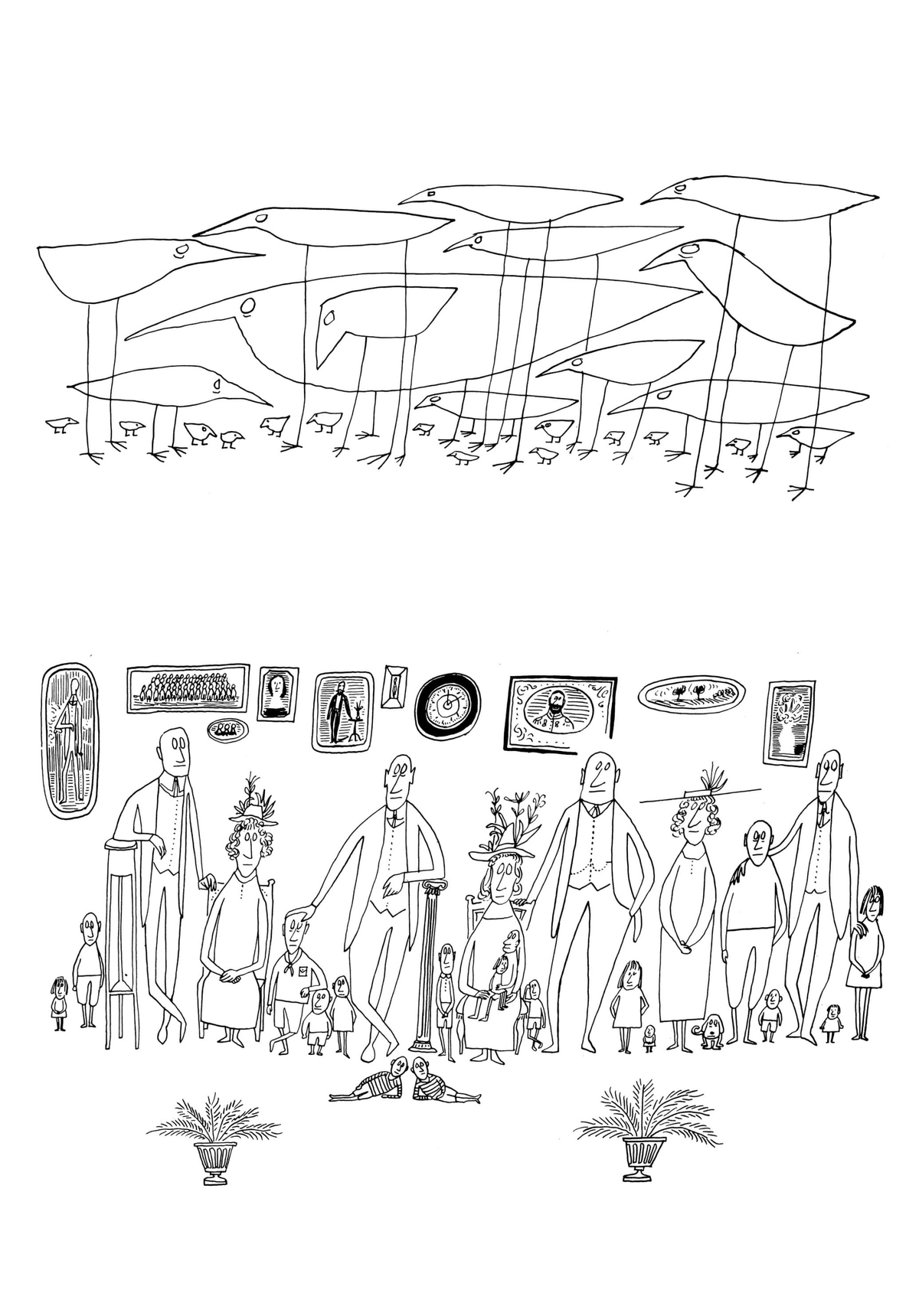

Steinberg’s 1945 monograph, All in Line, is now out in a new edition from New York Review Books; the introduction is by the New Yorker cartoonist Liana Finck. It’s a rare look into the mind of an artist who drew himself as a cat, a dog, and a fish, and who designed 85 New Yorker covers, including one that may be the magazine’s most memorable—View of the World from 9th Avenue. You know the image: a map in which everything west of the Hudson River is empty, undifferentiated space.

Steinberg himself had no such delusions of grandeur. “My line wants to remind you that it’s made of ink,” he once said. “I appeal to the complicity of my reader who will transform this line into meaning.” —Elena Clavarino

Elena Clavarino is a Senior Editor at Air Mail