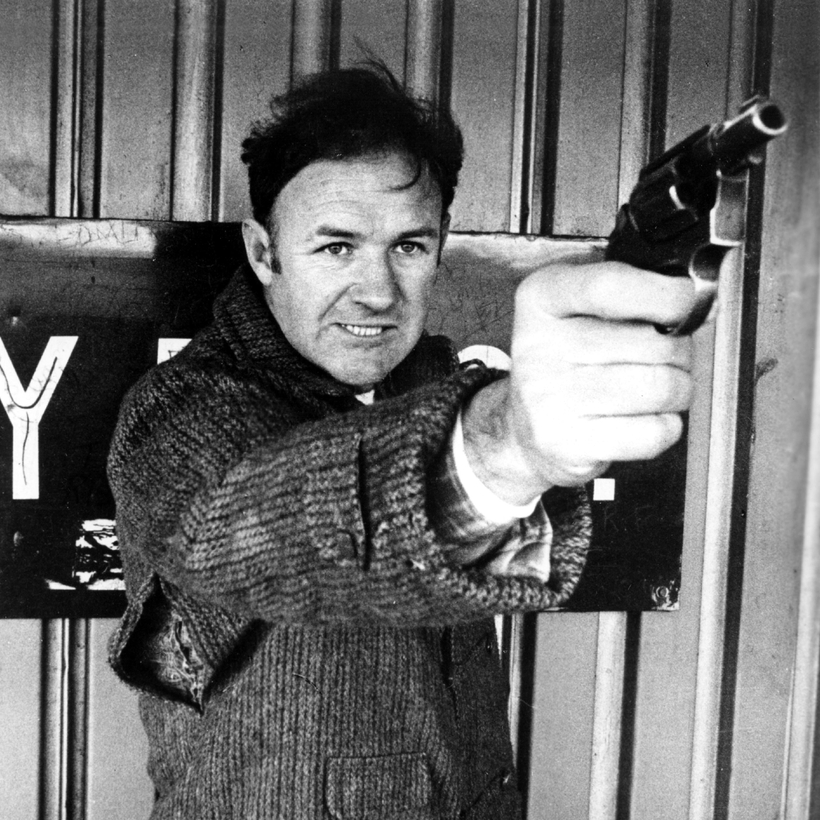

The death of the actor Gene Hackman at the age of 95 has left behind a whole raft of iconic and legendary roles, from Clyde Barrow’s brother (in Bonnie and Clyde) to supervillain Lex Luthor. Yet for many, the part that will never be beaten is that of Detective Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle, the abrasive, misanthropic protagonist of William Friedkin’s 1971 crime classic The French Connection. His character is introduced as the scuzziest Santa Claus imaginable, ringing his bells outside a bar in Brooklyn, before chasing and gleefully beating up a knife-wielding drug dealer.

It is one of the most economical and effective character introductions in cinema, combining visceral thrills with an element of black comedy, and showed that Hackman was perhaps the only actor who could have pulled off such a difficult part.