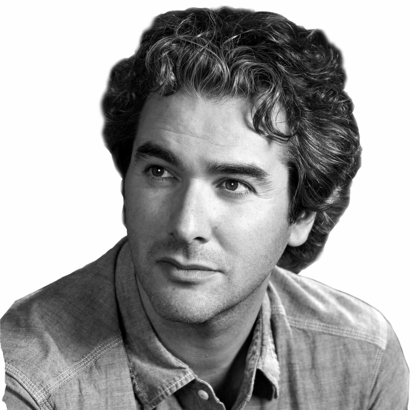

Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World by Dorian Lynskey

As wildfires ravage Los Angeles, Russia threatens nuclear war, and Donald Trump is sworn in as president again, it would seem an auspicious time for Dorian Lynskey’s compendium of millenarian imaginings. Then again, as this wide-ranging book attests, when wouldn’t it have been an auspicious time?

Lynskey charts our apocalyptic visions through the ages and shows that the end of the world has loomed over us since, well, the beginning of the world. Indeed, perhaps the only thing that binds people of all races, creeds, and colors together is the universal insistence that the end is nigh. From the Book of Revelation to Michael Bay’s Armageddon to more recent worries about rogue A.I., there is “no end of ends.”