Part of what makes Eleanor Coppola’s 1995 book, Notes: On the Making of Apocalypse Now, the best of its kind is her. After all, it was her apocalypse, too. Though as she so often denied, or felt she was made to deny, herself, I suspect she would deny her casual artistry was much more than jottings.

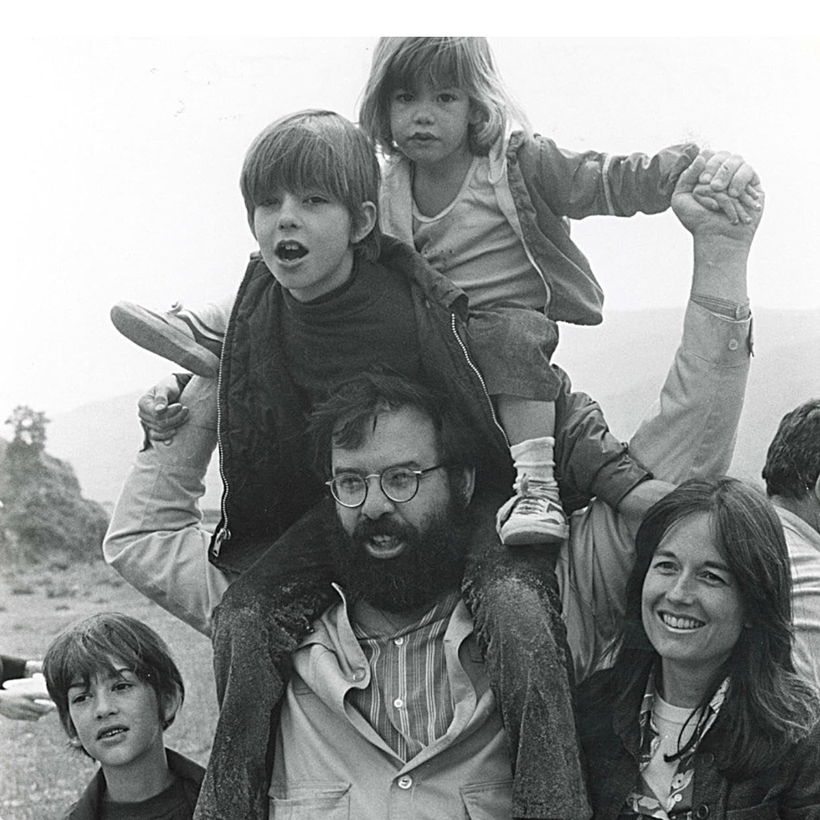

Eleanor, whose father was a cartoonist who died when she was young, had always dreamed of living a life of adventure as the wife of a powerful artist, but only a psychoanalyst would say she asked for everything the tropical typhoon she married had in store for her, him, the children. Wife, mother, or artist? Should she leave? Should she stay? This was her theme: How much art and life can we ask each other to sacrifice?