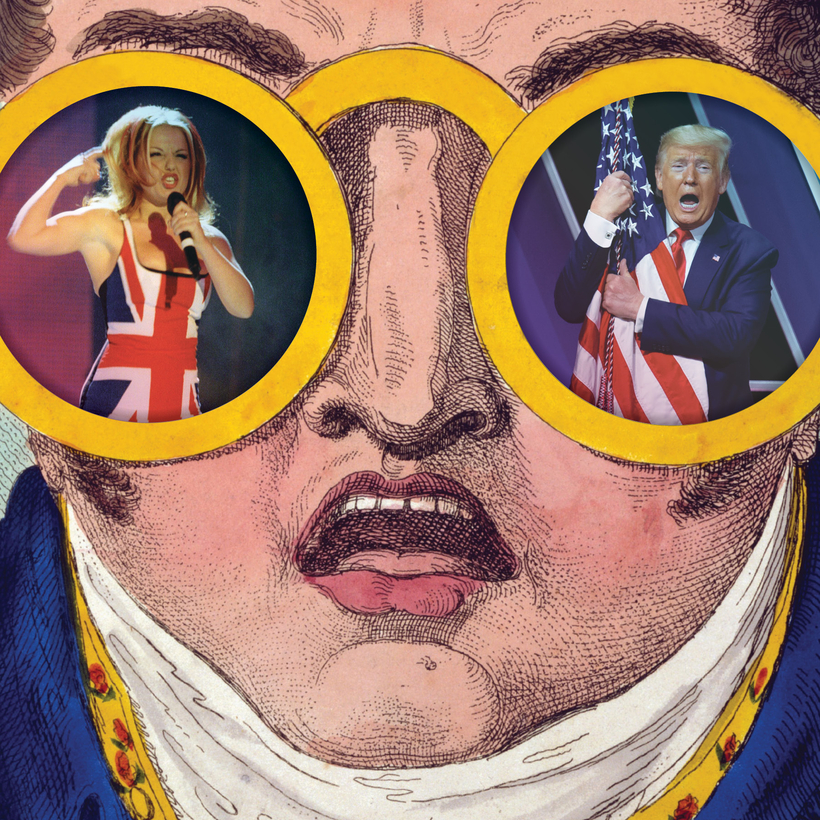

Is hanging your country’s flag outside your home a sign of pride or a statement of exclusion? Is it patriotism or nationalism? Does it unite or divide?

The answer to these questions might differ depending on where you’re from. In Denmark, national flags are displayed and waved as a form of celebration no matter the occasion, be it a birthday or a wedding. In the U.K., meanwhile, there’s a battle being waged over flags.