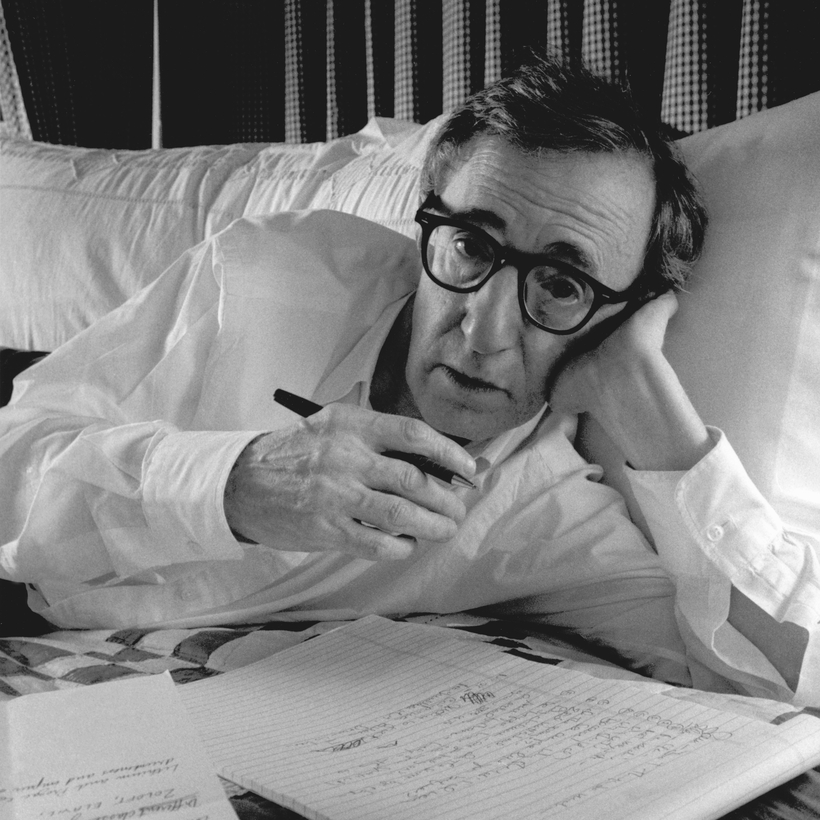

Dear Woody,

Recently, while interviewing you about your new novel, What’s with Baum?, I asked if you were proud of it. You said, “Oh, I never experience a sense of pride. When I’m finished with a movie or, in this case, a book, I always have a sense of: I don’t want to re-read it, I don’t want to see it again. I’ll just want to make changes, and I’m not going to be able to, and so I walk away and move on to the next project.”