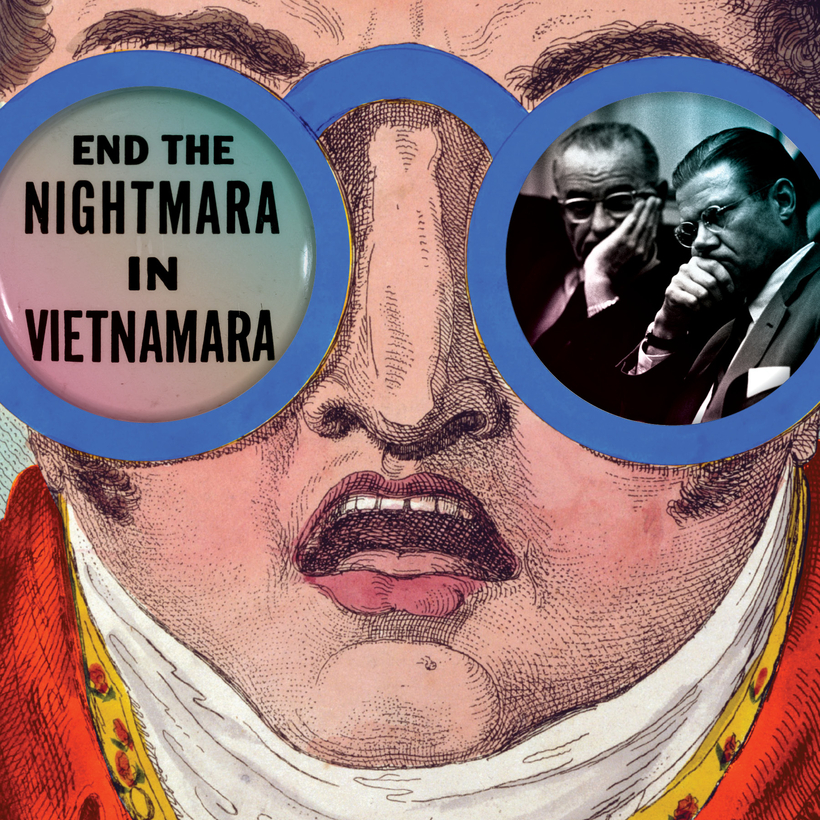

I became involved with Robert S. McNamara, the secretary of defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson who oversaw the beginning of the Vietnam War, because of a book he wrote with historian James G. Blight called Wilson’s Ghost: Reducing the Risk of Conflict, Killing and Catastrophe in the 21st Century (2001). It was not McNamara’s book In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (1995) that interested me, although I had read it. It was Wilson’s Ghost. Why?

The book had a curious format, with commentary by Blight and transcribed interviews with McNamara, printed in an alternate typeface. It introduced me to material that was not part of In Retrospect. There was something about the unvarnished reflections of someone who had an immediate connection with central events in history that I found compelling. And I felt very strongly, as a proponent of first-person interviewing, that I should endeavor to get McNamara on film.