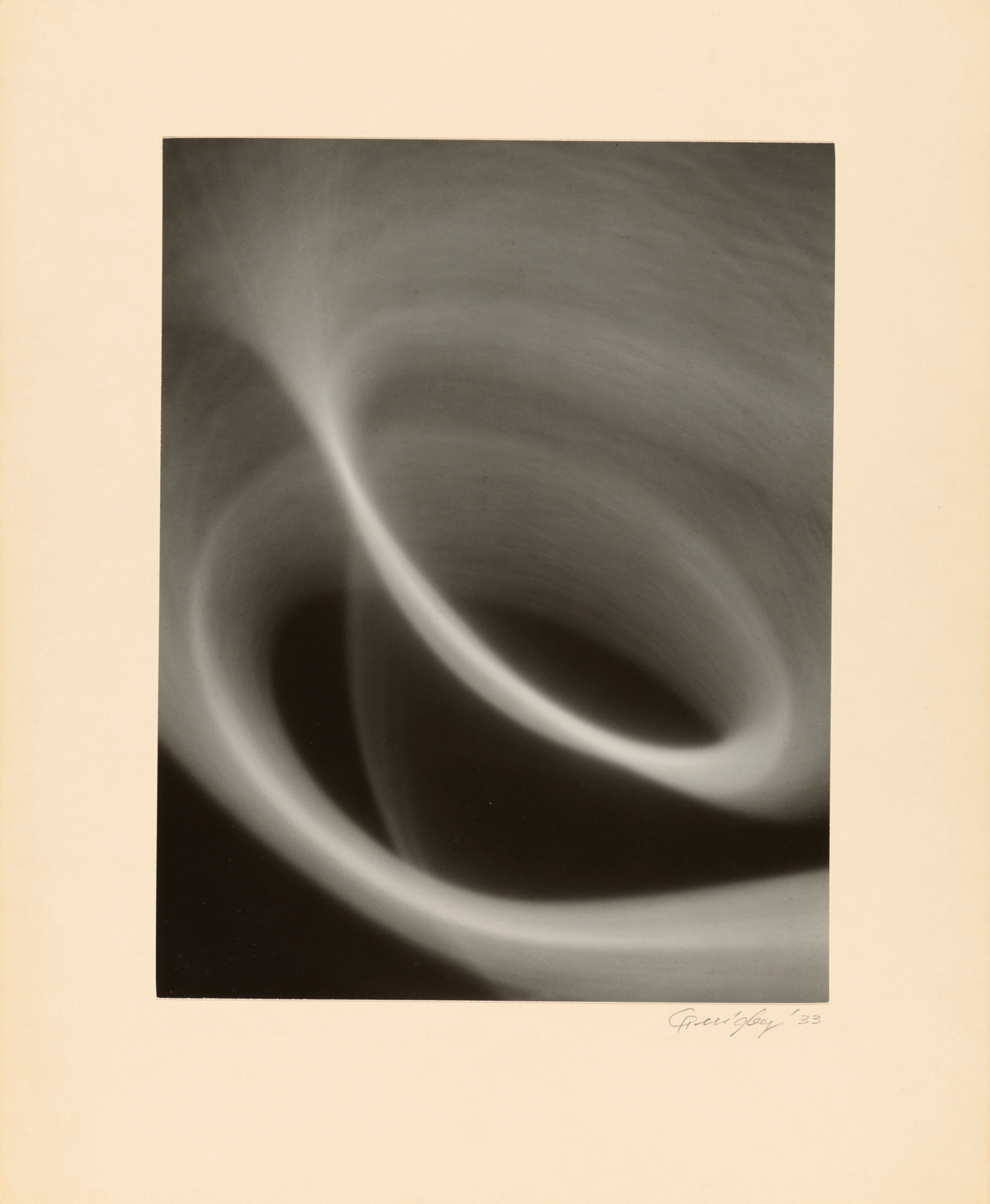

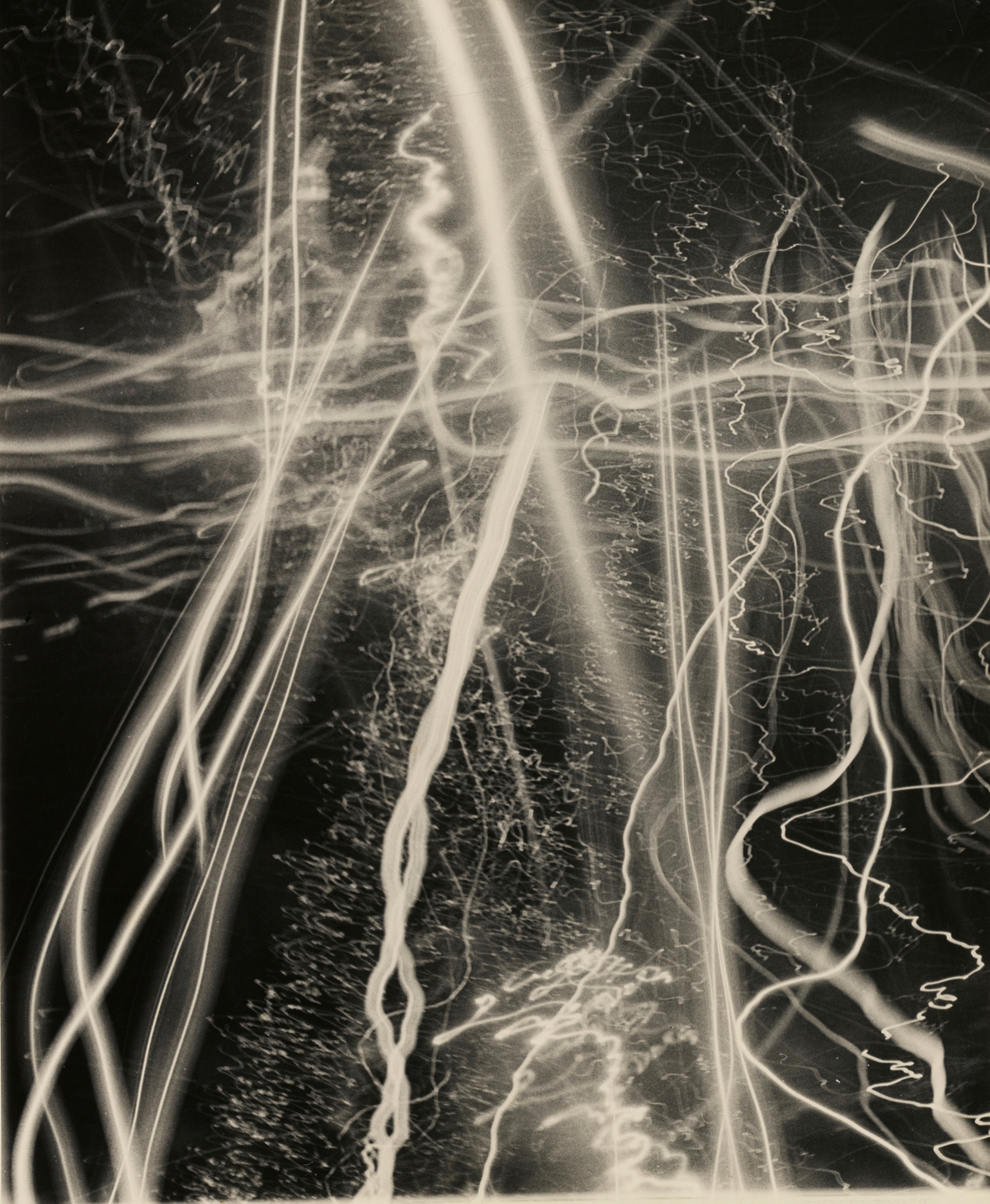

“This is the century of light,” the Hungarian-born painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy declared in 1927. “Photography is the first form of the formal design of light.” Film, he added, “goes even farther in this direction.” Most of us don’t think specifically of light when looking at a photograph or watching a movie. We’re caught up in the image. But there are photographers and filmmakers whose sole subject is the play of light itself, and they’ve sometimes done away with the camera completely. With the art of photography approaching its two-century mark, the Getty Center, in Los Angeles, has just opened the exhibition “Abstracted Light: Experimental Photography,” a survey of early- and mid-20th-century artists who made light their subject.

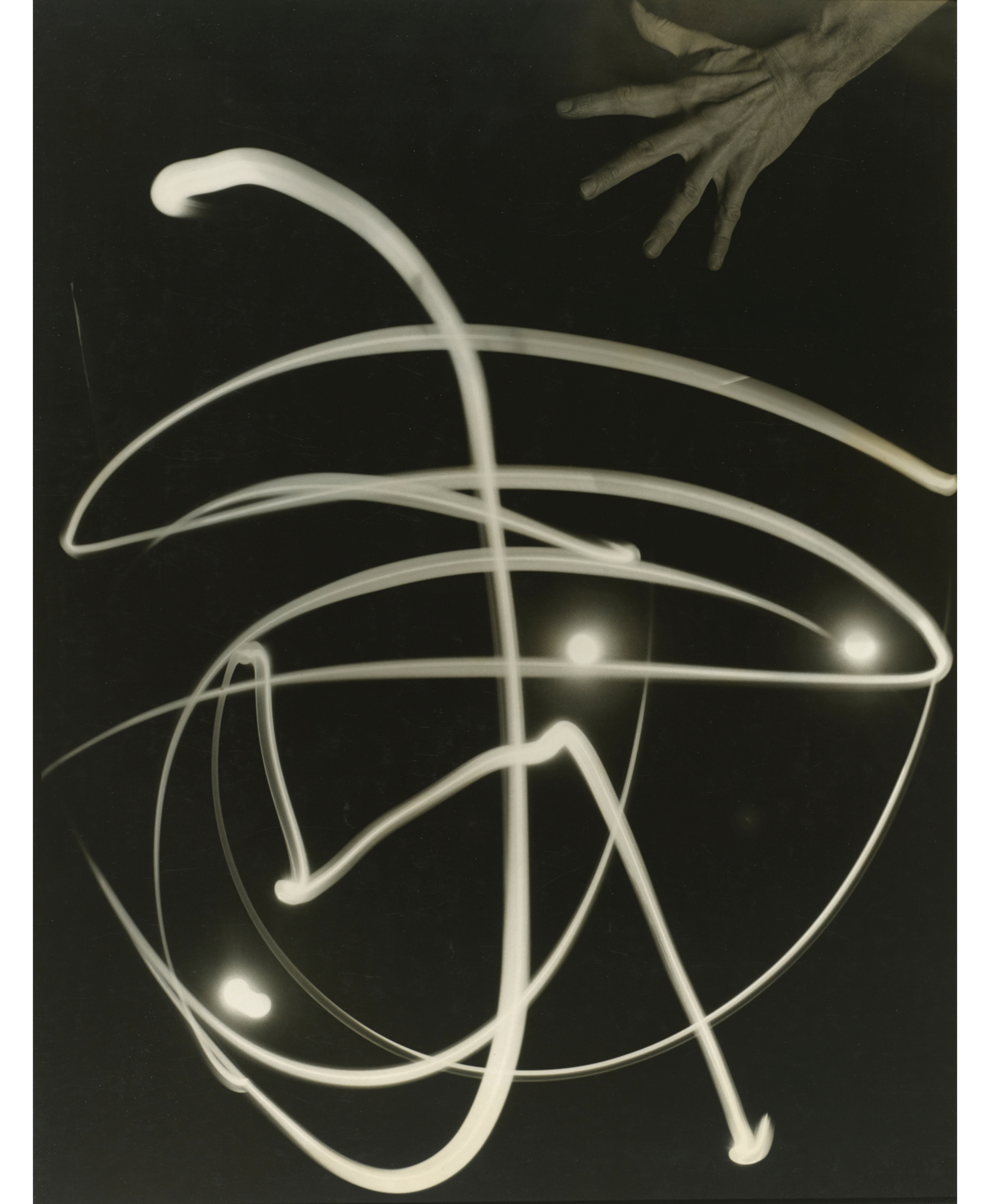

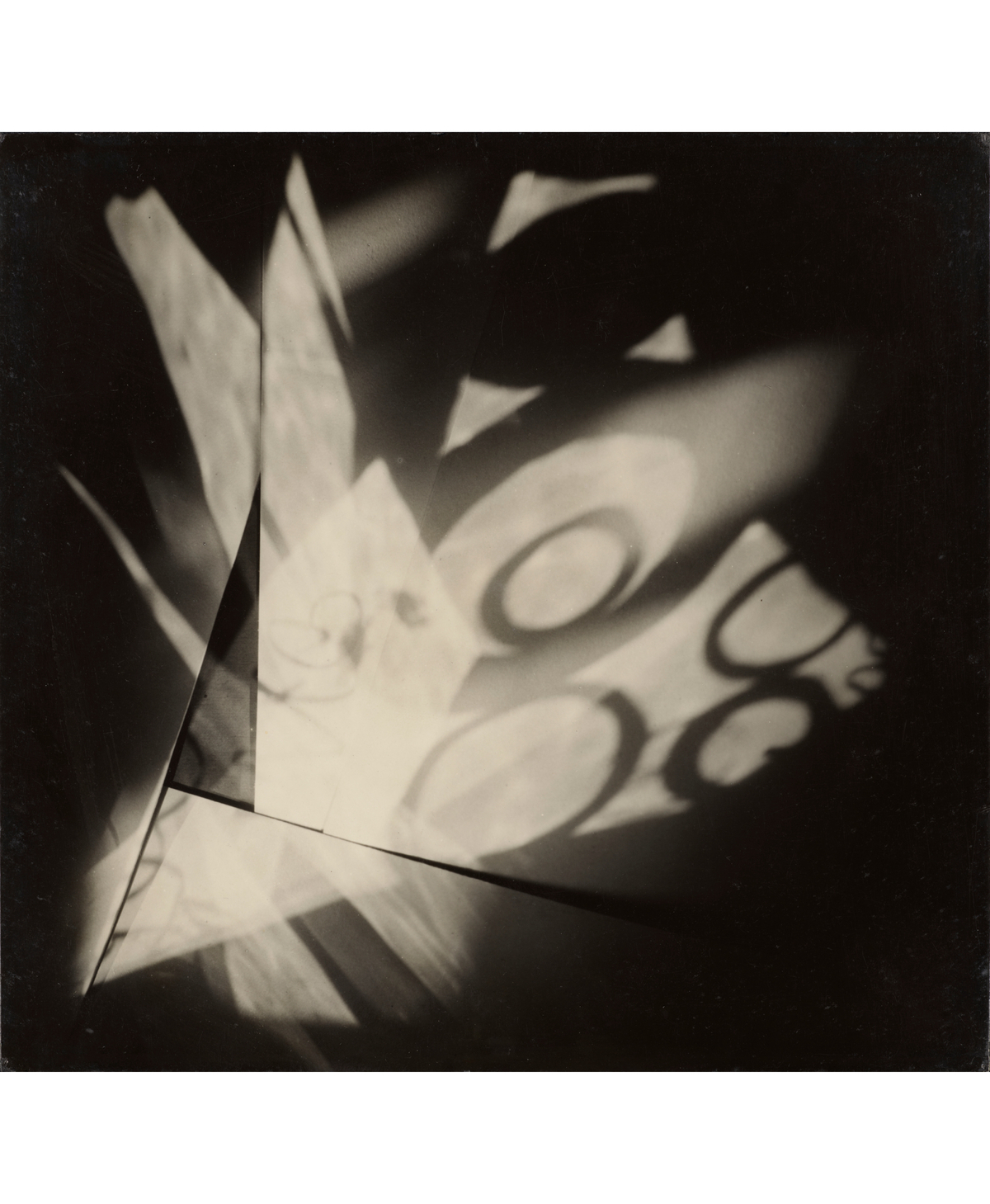

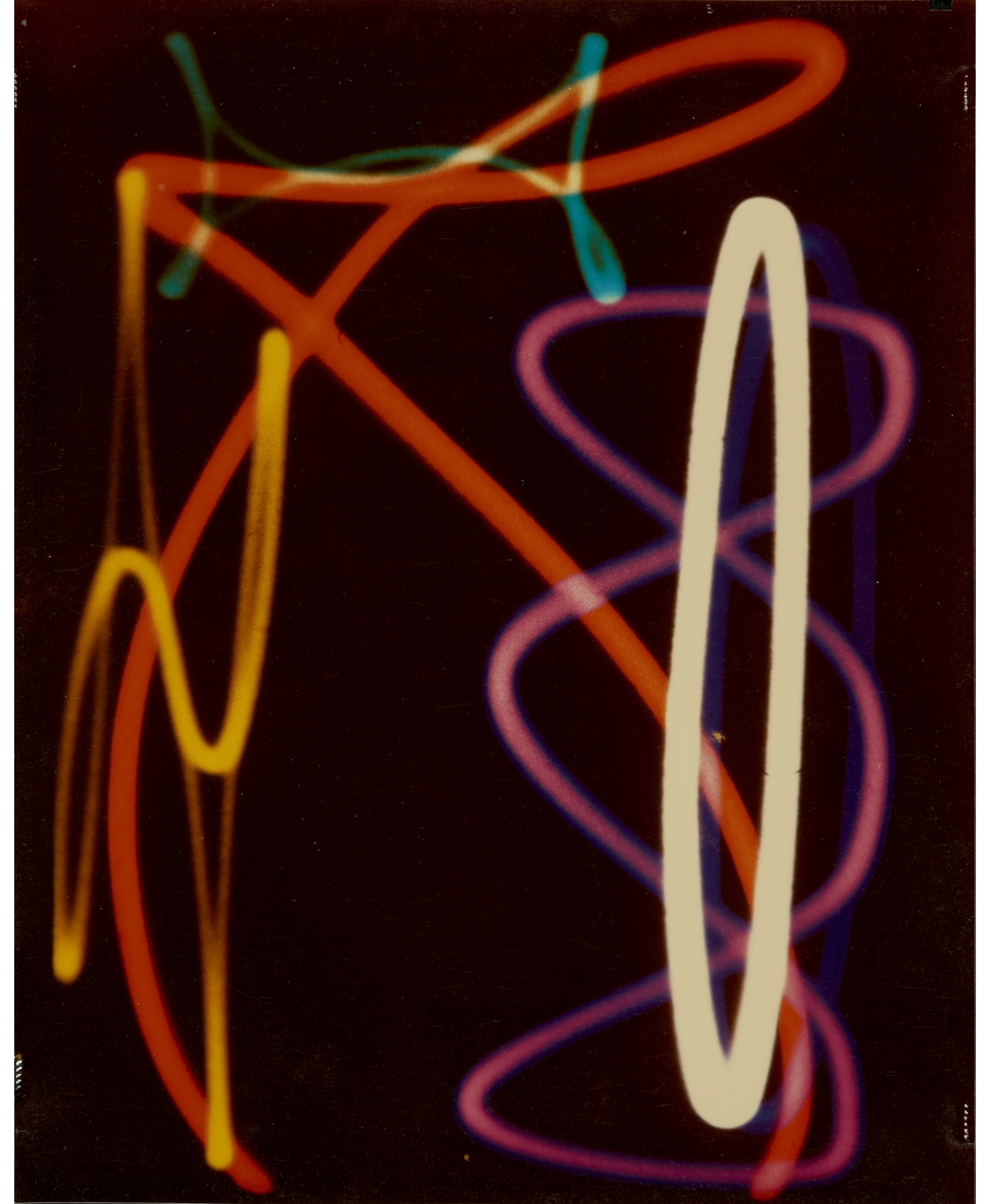

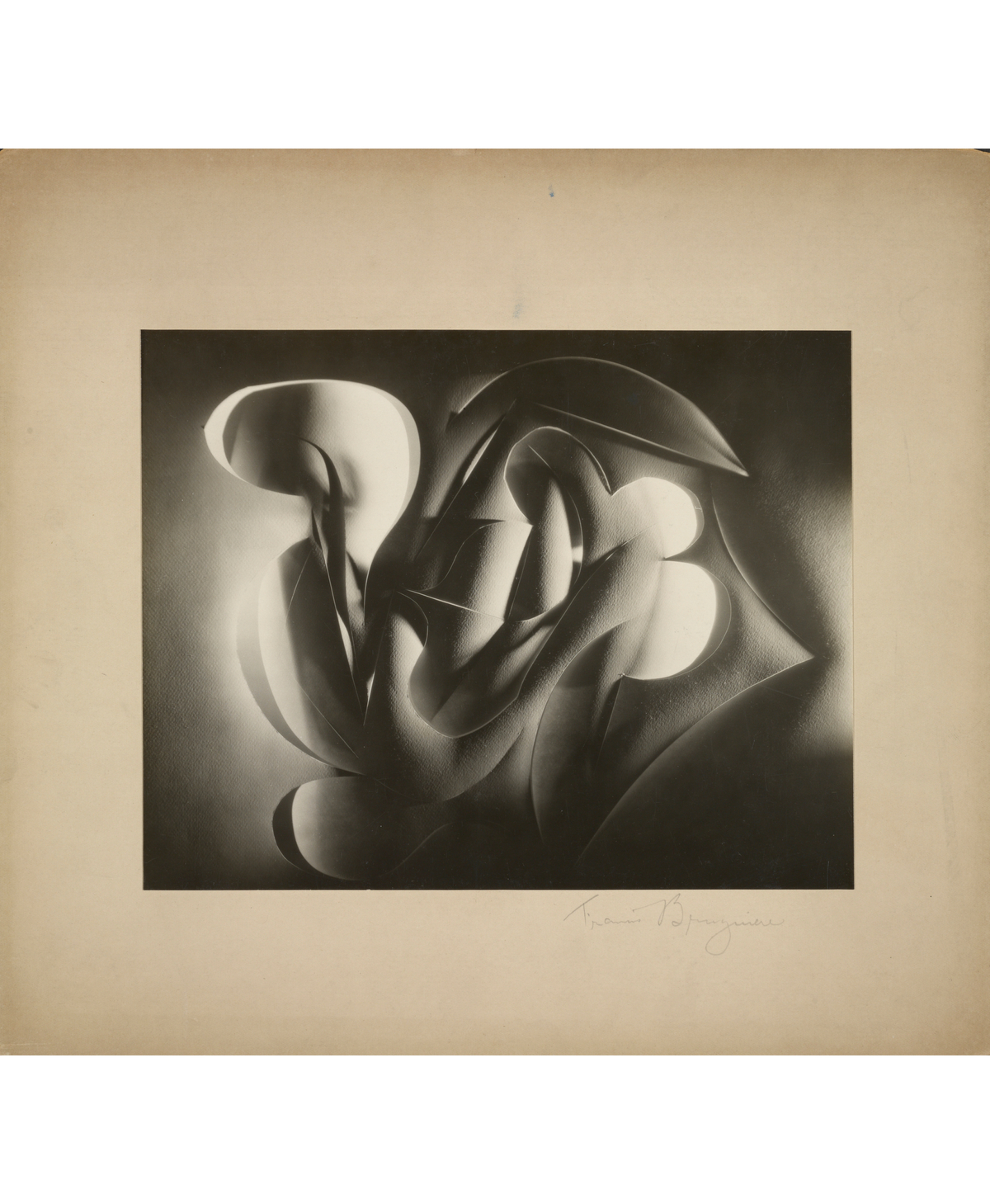

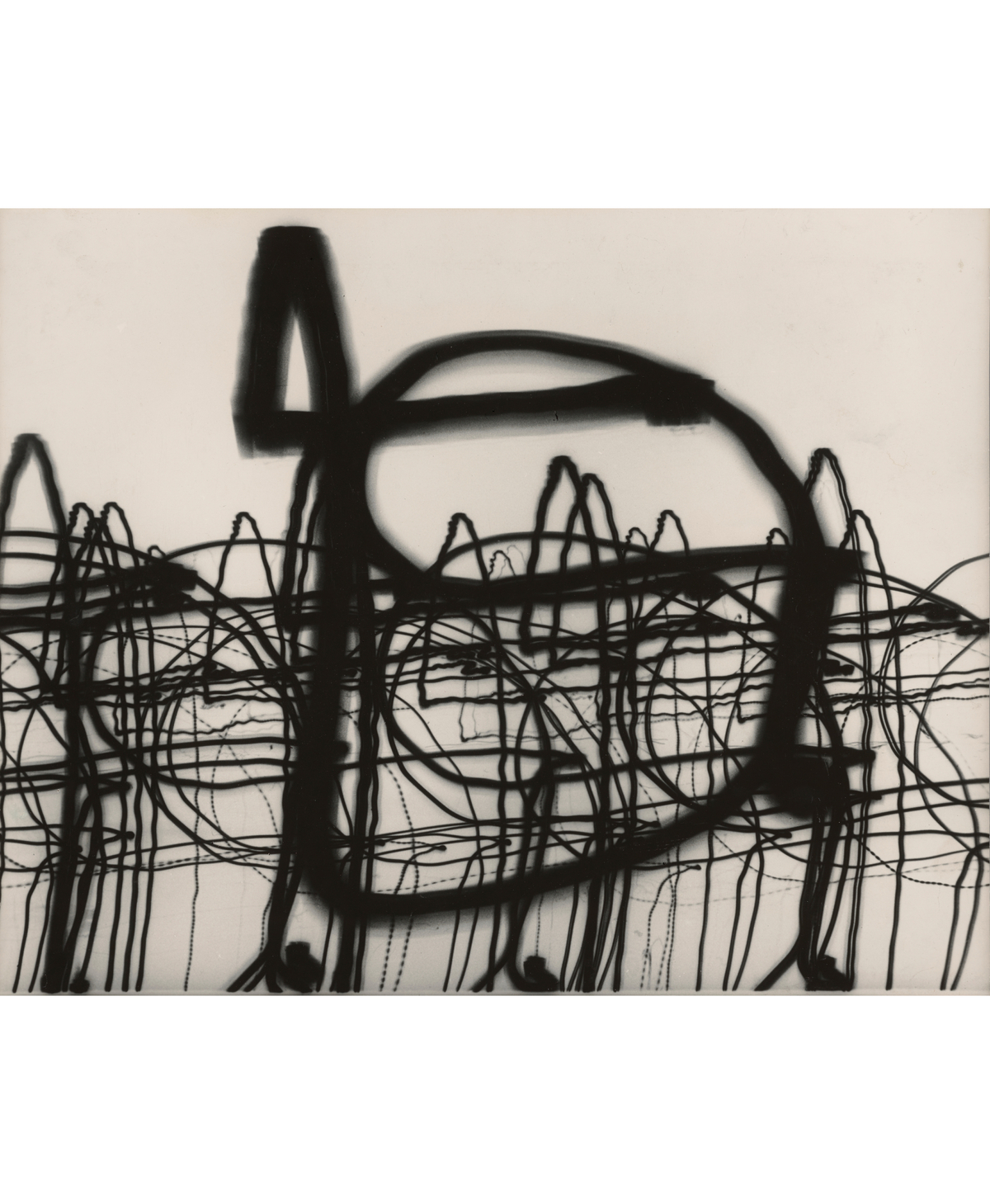

Science is never far from the work of the 26 artists represented in “Abstracted Light.” Many of them revived the photogram, a technique that dates back to photography’s earliest days and sees objects placed directly on light-sensitive paper. After W.W. I, Surrealism was on the rise, and what constituted representation was very much in flux. In the mid-1920s, Moholy-Nagy threw matches and napkin rings across a light-sensitive surface to create the ghostly Fotogramm, while in Paris, the Philadelphia-born Man Ray made photograms of scissors, paper, alphabet stencils, and a gun—all stylized images squarely in the Surrealist tradition of making everyday objects strange.

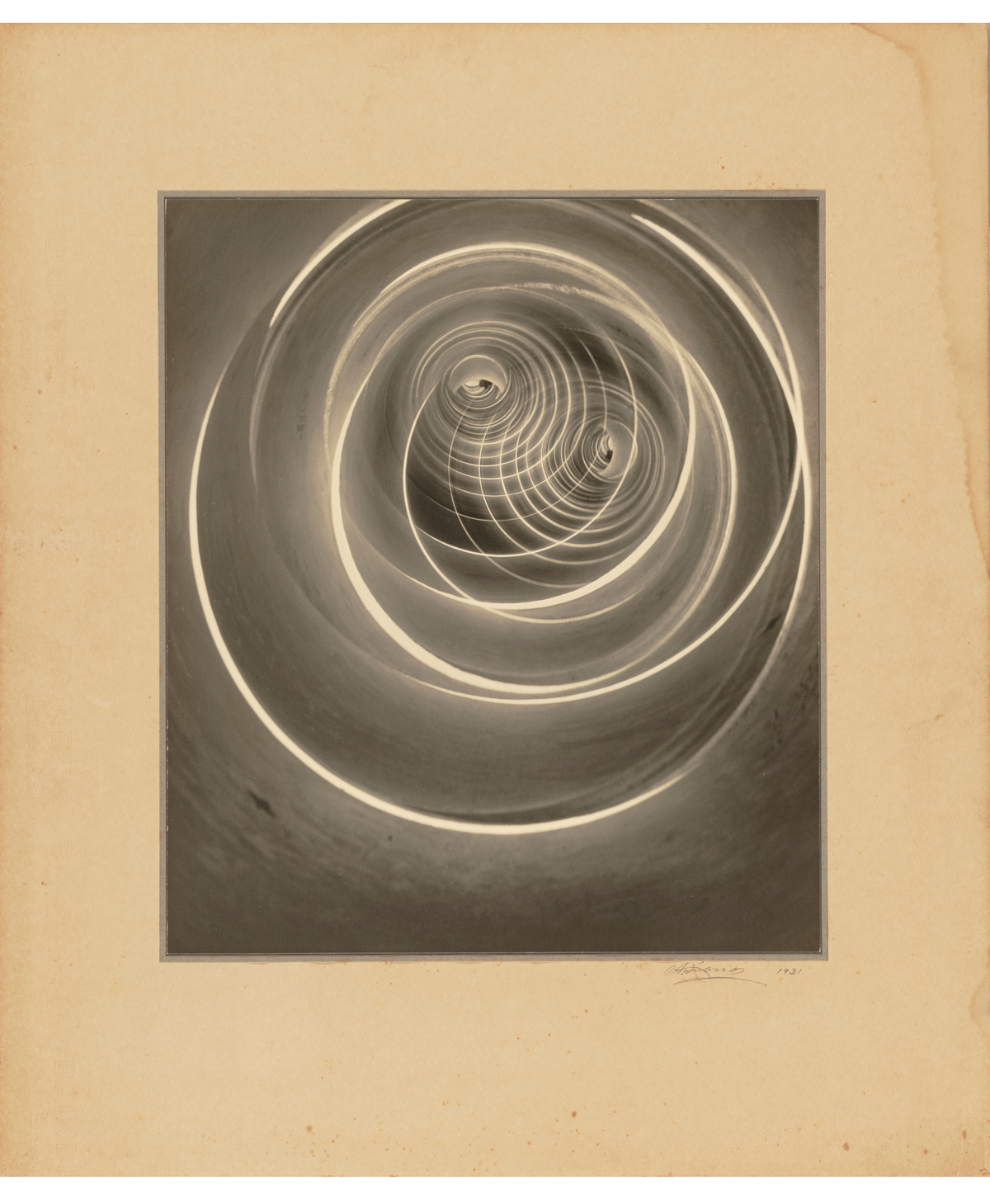

Some of the artists in the exhibition differentiated themselves by inventing machines or instruments that embodied their ideas. For instance, in 1930 Moholy-Nagy created the kinetic Light-Space Modulator—also called the Light Prop for an Electric Stage—a shiny metal structure of perforated disks, spinning mesh, and rotating spirals. The show contains a photograph of the device that only begins to suggest the complex moving patterns of light and shadow it (and its replicas) can project.

Thomas Wilfred’s work in light largely survives as a set of machines that display, like a television screen, a constantly changing array of effects. Wilfred was a Danish immigrant who came to New York after an unfortunate encounter with an art teacher at the Sorbonne, who criticized his desire to work directly with light. In the Getty show, four revamped Wilfred machines reanimate his works, which he identified with opus numbers, as in classical music. (He was an accomplished lutist.)

Though Yale University has put recordings of Wilfred’s programs on YouTube (some of which, theoretically, can last many hours without repetition), Getty curator Jim Ganz says the only true way to appreciate what Wilfred called “lumia” is to see them up close. Wilfred believed he had created an eighth art, alongside painting, sculpture, literature, architecture, theater, film, and music—the art of light. Inside his boxes, carefully calibrated motors, color wheels, mirrors, and light bulbs create shows that have been compared to the aurora borealis. Cosmic they are. Think creation of the universe, mysteriously captured in a set of 3D videos.

In contrast, Mary Ellen Bute’s explorations of light are fast, loud, short, and often funny. More than once, her films played New York’s prestigious Radio City Music Hall, presumably wedged between the main feature and the Rockettes. Bute specialized in abstract interpretations of short, popular classical pieces. In “Rhythm in Light” (1934), the short film at the Getty, the rings, balls, chains, and spikes gyrating to Grieg’s “Anitra’s Dance” were created by such things as Ping-Pong balls, sparklers, bracelets, prisms, and cellophane.

Born in Houston in 1906, Bute braved a world of few female animators and held her own for decades. To work out some of her animation based on trigonometry, she consulted the editorial board of a Yeshiva College publication. Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940) opens with a Bach toccata that Bute had successfully interpreted in 1937. And as a head trip, a role Fantasia has played since the 1960s, Bute’s film does just fine.

“Abstracted Light: Experimental Photography” is on view at the Getty Center, in Los Angeles, until November 24

Peter Saenger has written and edited for The Wall Street Journal on such topics as art, art books, museums, and travel. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker