The history of Communism and its standard-bearers in America is one of fascinating paradox and maddening waste. For the outcome of party membership, and even passing flirtation with its dogmas, was binary: either tragic delusion or sober retrospection. The movement’s finest accounts are exercises in the latter.

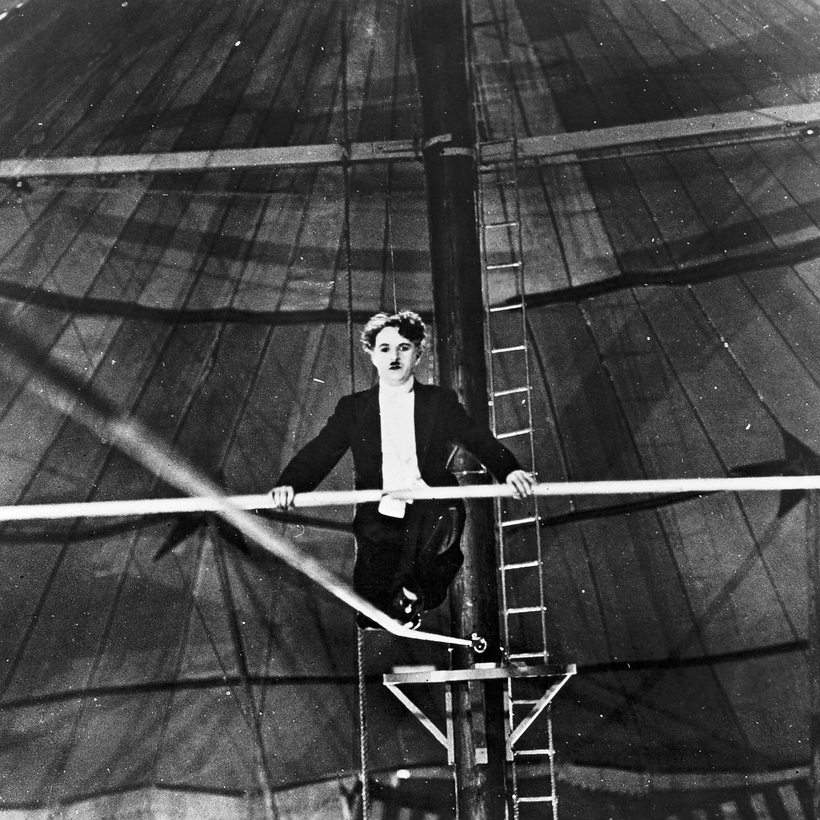

Any reading list ought to include Lionel Trilling’s 1947 novel, The Middle of the Journey (“Better, perhaps, to stay in the self-hatred of an enforced conformity than to enter the self-suspicion of even reasoned and justifiable treachery”), and the confessional essays of The God That Failed (1949), edited by Richard Crossman. “Having experienced the almost unlimited possibilities of mental acrobatism on that tight-rope stretched across one’s conscience,” Arthur Koestler reflected in the collection’s opening entry, “I know how much stretching it takes to make that elastic rope snap.” Maurice Isserman’s Reds: The Tragedy of American Communism belongs in their company.

For the first two decades of the 20th century, the Socialist Party of America (S.P.A.) occupied an important position on the country’s political left. Yet the S.P.A.’s equivocal response to the rise of the Bolsheviks and their bent for reform rather than revolution split members and resulted in the formation of the Communist Party USA (C.P.U.S.A.). The C.P.U.S.A.’s policies would never shake the influence of the Soviet Union, which can be traced, at least initially, to the journalist John Reed’s breathless reporting from Russia in 1917.

Reed is remembered today for his chronicle of the Russian Revolution, Ten Days That Shook the World (1919), and the Hollywood version, Reds (1981), Warren Beatty’s Oscar-winning epic about his life. When the screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky was consulted during the movie’s development, he found it difficult to wring meaning or moral drama from Reed’s—and perhaps, by extension, Beatty’s—self-absorption. “We’ve got a guy who falls in love with his role in history,” he wrote in his treatment, “which is all he ever really wanted.”

In the book Reds, Isserman quotes the literary critic Irving Howe on this before-and-after phenomenon: at first, “hardly anyone in America really knew what was happening in Russia.... Once, however, John Reed started filling the pages of the Liberator with his brilliant narrative about ‘ten days that shook the world’—an account of the Bolshevik revolution with the imperial simplicities of myth—then the American radicals could find a source of guidance and inspiration: this is how it happened, this is how it’s done.” As events were to prove, circumstances in America and the Soviet Union were virtually nothing alike.

The C.P.U.S.A.’s policies would never shake the influence of the Soviet Union.

Of America’s roughly 40,000 Communists in 1919, only 12,000 persisted two years later. The party’s false dawn was due partly to right-wing reaction after the war and partly to the reality that the Russian Revolution was, in Isserman’s words, “singular and exceptional” and “in no sense prophetic of the impending demise of capitalism, particularly American capitalism.” The czarist regime was “both brutal and decrepit, discredited by repeated military defeats, unable to count on the loyalty of its own army or navy, overseeing a faltering and largely agricultural economy,” while America was an ascendant power.

On the credit side of C.P.U.S.A.’s ledger were its defense of the Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in their controversial murder trial in the 20s—xenophobia clouded the proceedings and may have led to their execution, in 1927—and of the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers wrongfully accused of raping two white women in Alabama, in the 30s.

Of America’s roughly 40,000 Communists in 1919, only 12,000 persisted two years later.

Not surprisingly, the Great Depression and the Nazi threat provided the C.P.U.S.A. with an opening that even its most sectarian pedants—who had recently denounced socialists as “social fascists” and celebrated William Z. Foster’s “go-it-alone belligerence” in Toward Soviet America (1932)—could recognize. The result was the Popular Front, an “attempt,” Isserman relates, “for the first time to build bridges between [the C.P.U.S.A.] and other Americans, whereas always before their inclination had been to erect barricades.”

Under the leadership of Earl Browder, the C.P.U.S.A. assumed an unfamiliar patriotism just as the Roosevelt administration turned leftward. By 1937, the organization was experiencing “the most successful worker insurgency in American history,” according to Isserman. “It must have seemed to the Party’s supporters as if they had found their way out of a long, dark maze of perennially lost causes, into newfound legitimacy and relevance.” The C.P.U.S.A. went so far as to support Roosevelt’s re-election.

It was not to last. As Isserman points out, “the height of the Popular Front’s era of democratic good feelings in the United States, 1936–1938, was also the height of Stalin’s murderous purges in the Soviet Union.” Stalin’s shocking pact with Hitler in 1939 exploded the prevailing solidarity and divided loyalties. “In the Red Scare of 1919–1920,” Isserman remarks, “none convicted under the misnamed Espionage Act had actually committed espionage, or anything like it.... However, charges of ‘espionage’ in the 1940s and 1950s were not always instances of malicious hyperbole.”

Isserman maintains an impressive balance between the C.P.U.S.A.’s positive achievements and, well, everything else. The party “helped win democratic reforms that benefited millions of ordinary American citizens, at the same time that the movement championed a brutal totalitarian state responsible for the imprisonment and deaths of millions of Soviet citizens.” Its adherents “prove[d] themselves skilled organizers of powerful industrial unions that served hundreds of thousands of rank-and-file members well, while at the same time clinging to fundamental and tendentious misunderstandings and fantasies about the lives and political outlook of working people in the United States.” Reds deserves similar praise for its concision, even if I would have enjoyed Isserman’s take on the comparative trajectories of other Communist factions in the West.

One wonders whether those who forged the C.P.U.S.A. would, with the benefit of hindsight, be proud or horrified that their creation survived the fall of the Soviet Union. They might be amused, at any rate, to know its headquarters are on West 23rd Street in Chelsea, between Lions & Tigers & Squares Detroit Pizza and Gym U NYC.

“If we lived long enough to see the results of our actions,” Oscar Wilde observed, “it may be that those who call themselves good would be sickened with a dull remorse.” Isserman’s epitaph for the C.P.U.S.A. is hollower still. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, in 1991, “a faithful few still clung to the Party, as always their church and citadel. But the church and the citadel stood for and guarded nothing, nothing but ashes.”

Max Carter is vice-chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art at Christie’s in New York