In 2002 the gallerist Mitchell Algus opened a solo show of black-and-white paintings by the artist Betty Tompkins that, for 30 years, other dealers had refused to exhibit. The pieces, now known as Tompkins’s “Fuck Paintings,” featured close-up depictions of genitals mid-coitus.

A curator saw Tompkins’s work at Algus’s gallery and, impressed, included it in a prestigious biennial in France. Soon after, a piece was purchased for the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Now, Tompkins’s paintings sell for upwards of $500,000 and hang in museums around the world. Algus, Tompkins has said, “was like a fairy godmother.”

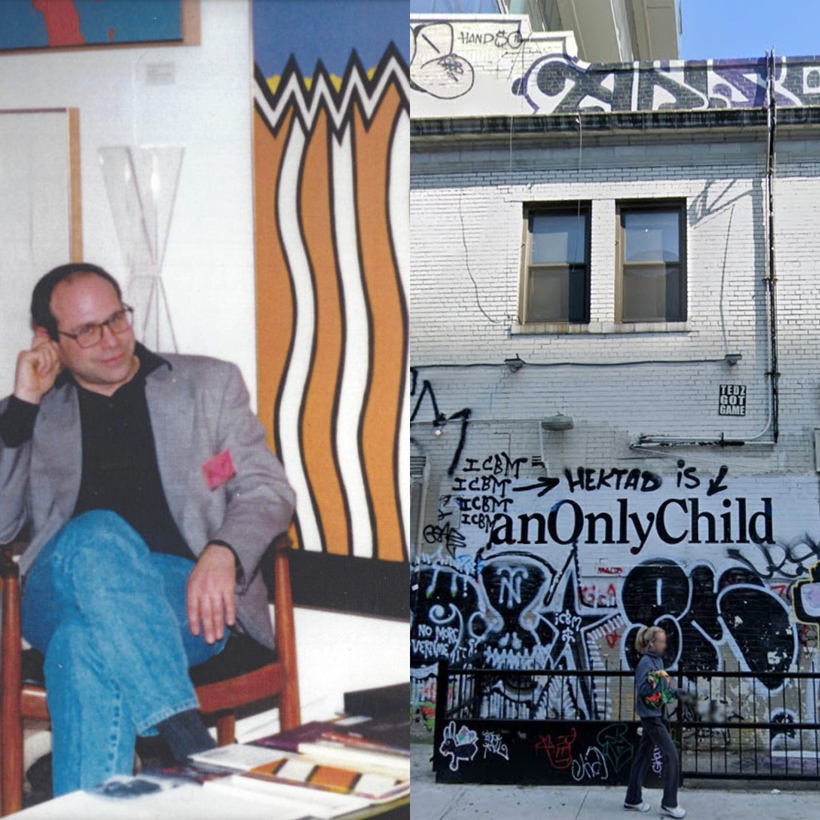

Most halfway-decent art dealers have a story about “discovering” artists who have gone on to make it big. But few, if any, have racked up as impressive a track record as Algus while continuing to operate in relative obscurity. If there is an anti–Larry Gagosian—impervious to trends, indifferent to making money—it’s Algus.

In the three decades that he’s run his eponymous gallery—which, until he started drawing a pension in 2014, he supported off his salary as a public-school teacher—Algus has quietly earned a reputation for championing artwork by little-known artists, many of whom, like Lee Lozano, Barkley Hendricks, and Judith Bernstein, have gone on to become major sensations, though without any great financial windfall for Algus.

What he has amassed is a dedicated following of curators, critics, and artists (Robert Gober among them) who call Algus “a secret source,” an “art-world oracle,” and “one of the great outliers in New York gallery history.” “I’ve been to hundreds and hundreds of galleries,” says Bob Nickas, a critic and curator who organized a solo show of Lozano’s artwork at MoMA PS1 after first encountering it at Mitchell Algus Gallery. “I only know two that I could say, very confidently, the owners had a vision. And one is Mitchell.”

Most halfway-decent art dealers have a story about “discovering” artists who have gone on to make it big. But few, if any, have racked up as impressive a track record as Algus.

On a recent afternoon, Algus sat in his gallery, on the Lower East Side, above a graffiti-covered discount-jewelry store. In his office is a painting that marked one of his early encounters with art as a kid growing up on Long Island. The piece, a 1956 work by Jules Kirschenbaum depicting limp, naked men being attacked by pterodactyls on a playground, had hung above the television set in the home of a childhood friend whose father introduced Algus’s father, a periodontist, to art collecting.

Algus started tagging along on his father’s visits to museums in New York City, and a passion took hold. In between field research in the Canadian tundra and a Ph.D. in physical geography, he pored over art magazines, toured galleries, befriended artists, and made his own art: precarious towers of seashells and upholstered cushions that look like magnified E. coli bacteria.

Algus moved to New York and opened his first gallery, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 1989. He began teaching high-school science, a job that allowed him the flexibility to show what he wanted without worrying too much about selling. “I just want to do my shows,” he says. “That’s my pay.” The satisfaction, for Algus, is exhibiting something “that’s great and that nobody’s paying attention to.”

Algus wants each show to feel like a discovery. He has shown art he found in storage units and on eBay, by octogenarians and artists barely out of school. On past visits, I’ve seen brushy pastel landscape paintings dotted with acrobats, abstract works conjuring mysterious Martian landscapes, and an impressively realistic portrait of Andy Warhol painted by an artist using a brush stuck up his butt.

Algus walked me through a recent exhibit, a solo show of pencil drawings by the artist Morgan O’Hara featuring swarms of gray lines made by following the hands of people engaged in tasks such as carving a gondola or gesticulating on a Zoom call. He fell in love with the work when O’Hara, then in her late 70s, marched into the gallery one day to introduce herself. Algus liked that the pieces could seem like scribbles but weren’t. “There are secrets in each show, hopefully,” he says. Currently on view is a show of paintings by the late artist and architect Gerhardt Liebmann, which is not to be missed.

In its commitment to showing artists Algus considers unfairly neglected, the gallery stands as a rebuke to the art market’s fickle and arbitrary tastes. The exact same drawings by Lozano that Algus struggled to sell for $1,800 apiece have sold for more than 30 times that amount at Hauser & Wirth, which snapped up the late artist’s estate shortly after her show at MoMA PS1.

He has shown art he found in storage units and on eBay, by octogenarians and artists barely out of school.

“The art world is a huge problem,” Algus says. “I thought that the work itself would focus interest. But it’s not that simple.” While many connoisseurs base their opinions of art on its “context”—essentially the pedigree of an artist and her supporters—Algus just looks at the art. As we spoke, he couldn’t help leaping up every few minutes to pull a monograph from the bookshelf so he could illustrate the point in question, and once he whipped out his phone while doing 60 on the freeway to show me a painting by a long-dead artist he’s obsessed with.

Algus spent the pandemic crisscrossing the tri-state area hunting for overlooked midcentury-modern architectural treasures, a pilgrimage that led him to the work of late architect Myron Goldfinger, whose drawings and models Algus will exhibit this fall.

That is, if he can continue to pay the rent. A few years ago, he announced on Instagram that the gallery was “on the verge of closing.” A false alarm, as it turned out, but he is actively exploring potential collaborations. He showed me a Word document he’d put together listing more than two dozen artists he’d exhibited who had since gone on to bigger galleries—a way, he hoped, of marketing himself, and of keeping the lights on.

“I’m not one of those persons who can say, ‘Oh, I’m doing special projects,’ or ‘I’m spending more time with my family, blah blah blah,’” he says. “If the gallery ceases to exist and I’m not out there, I cease to exist.”

Bianca Bosker is the author of Get the Picture and Cork Dork. She’s a contributing writer for The Atlantic and has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal