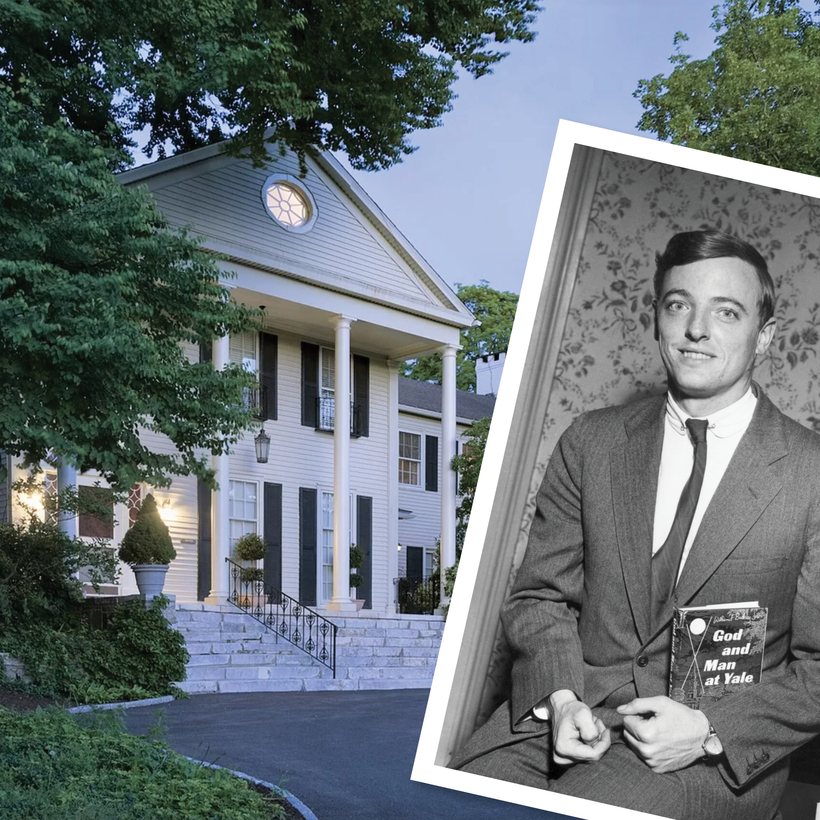

Those recently browsing Zillow for 19th-century houses in New England may have come across a piece of political history: the childhood home of conservative-movement-maker William F. Buckley Jr.

Great Elm, in Sharon, Connecticut, is a Georgian colonial originally built in 1812 and massively expanded in 1929 to some 30 rooms. The house was converted into five condominiums in the 1980s, and its two south-facing units, owned by Buckley’s nephew, are currently on the market for $5.5 million.

The two condominiums alone contain nearly 9,000 square feet of living space, with eight bedrooms, nine bathrooms, and seven woodburning fireplaces. There’s a colonial-era pine room imported whole from Philadelphia as well as a three-story, balconied atrium reminiscent of New Orleans, and the grounds sprawl for 50 acres, offering shared access to tennis courts and a Junior Olympic–size pool. The listing also advertises the house’s proximity to Buckley’s alma mater, Millbrook School, from which he graduated in 1943.

But it wasn’t Millbrook that made Bill Buckley. Rather, it was the bubble of Great Elm, “where William F. Buckley Jr.’s personality and soul formed,” says his son, Christopher. Behind Great Elm’s colonial columns and French doors, Buckley and his nine siblings lived out their father’s pedagogical dreams. The brood enjoyed lessons from tutors—Bill Buckley chalked up his transatlantic accent to learning Spanish and French before English—while also mastering how to sail, hunt, horseback ride, ballroom dance, and, naturally, debate.

In the airy atrium, Buckley would sit on his devoutly Catholic mother’s lap, listening to her tell stories from the Bible or the American Revolution. His father was an oil wildcatter, who had brought the atrium’s tiles back from Mexico when he had been forced to flee after siding with General Victoriano Huerta’s military coup against the democratically elected government. The Mexican government’s consequent meddling in his oil business bred in Buckley Sr. a distaste for big government and popular revolt he passed on to his progeny.

The Buckleys frequently welcomed guests to Great Elm, not least of whom was Albert Jay Nock, an Anglican priest turned libertarian intellectual who profoundly shaped Bill Buckley’s view of the world and his place in it. Nock’s concept of “the Remnant”—a chosen few destined to steer the masses and save civilization from collapse—would underpin Buckley’s philosophy, and the conservative movement, for decades.

Buckley chalked up his transatlantic accent to learning Spanish and French before English.

As a Yale undergraduate, Buckley railed against students’ supposed brainwashing by liberally biased, anti-religious faculty. Upon graduating in 1951, he published God and Man at Yale, lambasting the “intellectual elite” and setting off a counter-revolutionary career that saw the 1980 presidential election of Ronald Reagan, a Buckley acolyte, as its apotheosis.

Nevertheless, elitism thrived at Great Elm. The same year Buckley’s book was published, a 19-year-old Sylvia Plath, then a classmate of one of Buckley’s sisters, was left wide-eyed by a debutante ball held at the house, a weekend of champagne, chauffeurs, Whiffenpoofs—Yale’s a capella group—and “the most amazing repast brought in by colored waiters in great copper tureens.”

Nine years later, nearly 100 conservative college students would descend on Great Elm at the invitation of Buckley for a different sort of gathering. Buckley had won the students’ admiration through his campus lecture circuit, building a political movement from the ground up as he fashioned himself as a gadfly to the liberal establishment whose New Deal order, he believed, had turned tyrannical, even Communist. And so, at Great Elm, the Young Americans for Freedom—whose members are known as “Yaffers”—formed around him, a youth-activism organization that swore to uphold its founding statement of principles known as the “Sharon Statement.”

Just 400 words long, the Sharon Statement—named after the town in which Great Elm resides—listed five core conservative principles: the importance of individual freedom, economic freedom, the free-market system, a limited government combined with a strict interpretation of the Constitution, and, naturally, the defeat of Communism. (Two years later the Students for a Democratic Society responded with their own manifesto, the Port Huron Statement, which cast participatory democracy as their guiding force. It was more than 25,000 words long.)

The Yaffers grew up to lead the conservative movement of the past 60 years, siding with Barry Goldwater, funding Ronald Reagan, and heading such right-wing think tanks as the Heritage Foundation, all while espousing the primacy of states’ rights and unfettered capitalism.

Those of a liberal disposition might well flinch at the property’s starring role in the modern conservative movement, but it’s a long way from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago.

Carrie Monahan is a Brooklyn-based writer. She recently co-produced the PBS American Masters documentary The Incomparable Mr. Buckley