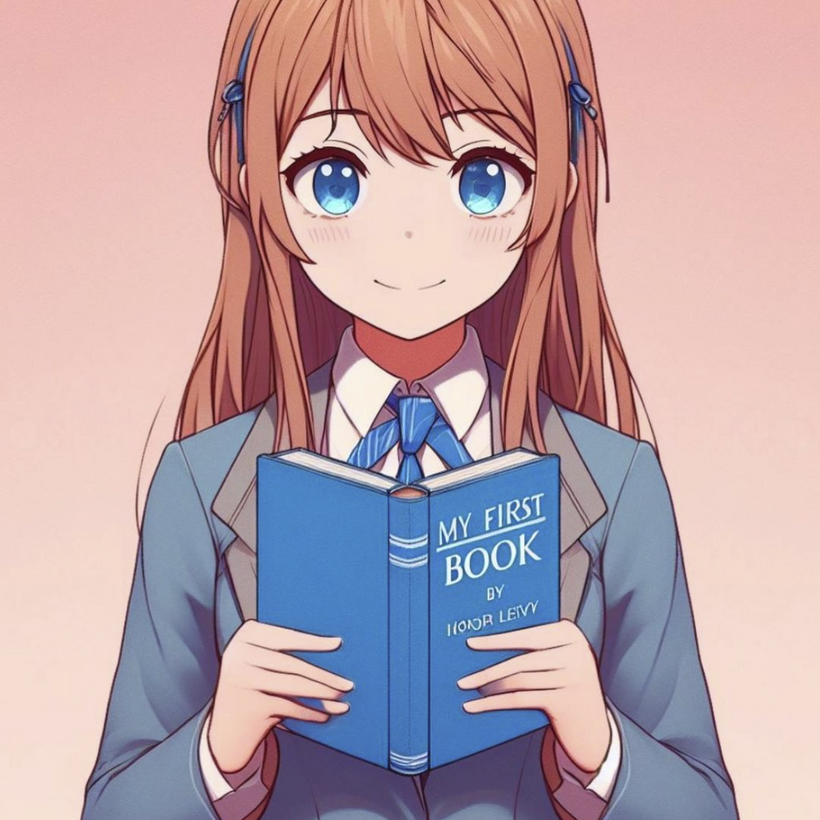

“It’s my first interview,” says Honor Levy, while vaping. Discussing her first book—titled My First Book, which will be published next week by Penguin Press—she lets me know that she actually quit vaping. “I needed something to calm me down,” the 26-year-old explains.

I first met Levy, who currently lives in Los Angeles, at a friend’s apartment-warming, in Manhattan, in 2020. At the start of the pandemic, Levy moved to New York while finishing her last semester at Bennington College, where she studied theater and playwriting. In person, she was like a blur, not only because she was in constant motion, circling the room, but because, in conversations, her opinions were adamantly unformed, bouncing from provocation to apologia.