In his 1969 memoir, Present at the Creation, former U.S. secretary of state Dean Acheson confessed the difficulty of navigating the shift from one historical paradigm to another—in his case, from cooperation with the Soviet Union during W.W. II to the onset of the Cold War. “The significance of events was shrouded in ambiguity,” he wrote. “We groped after interpretations of them, sometimes reversed lines of action based on earlier views, and hesitated long before grasping what now seems obvious.”

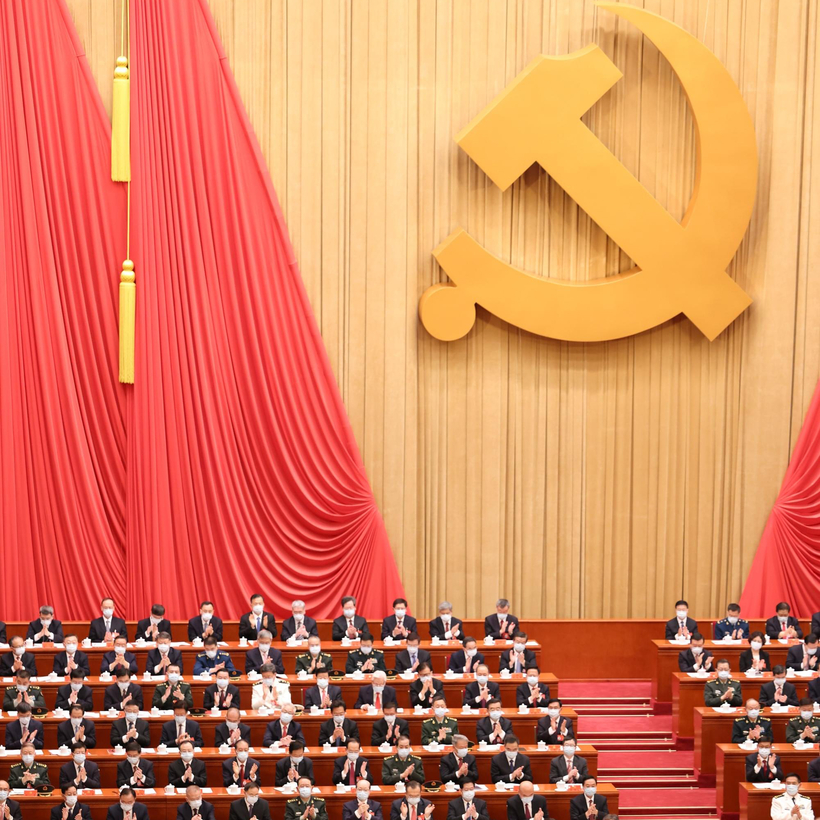

It’s clear that we’re living through a similar transition today. Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has ignited a land war in Europe of a scale not seen since 1945, while economic and military tensions with Xi Jinping’s China have accelerated dramatically and risk spiraling into conflict. Zooming out, state-to-state conflicts are at their highest level since the end of the Cold War, and total conflicts are at their highest since the end of W.W. II. Recognizing that history is again underway, President Biden declared in 2022 that “the post-Cold War Era is definitively over.”

What’s more uncertain is where we’re headed. The longtime—and extremely well sourced—New York Times correspondent David Sanger seeks out this story in New Cold Wars, his stellar history of Biden’s foreign policy.

State-to-state conflicts are at their highest level since the end of the Cold War, and total conflicts are at their highest since the end of W.W. II.

He begins by tracing the arc of U.S. policy toward Russia and China over the past few decades: from engagement and misplaced hopes to disappointment, tension, and rivalry. Courting Putin during the 2000s and crossing fingers that China would liberalize at home may now appear hopelessly naïve, but it’s hard to fault earlier administrations for trying engagement when events were “shrouded in ambiguity,” to quote Acheson.

Sanger then spends the balance of the book telling his deeply reported story of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, America’s response, and Biden’s steady ratcheting up of competition with Beijing.

A few key impressions emerge. One is just how close we may have been to nuclear war during the fall of 2022, as Ukraine’s successful offensive pushed Putin into a corner. U.S. intelligence, apparently, picked up on Russian military chatter about possibly using tactical nuclear weapons if Ukraine continued its march. Ironically, pressure from China helped convince Putin to sheathe his nuclear saber.

More broadly, Sanger describes the Biden team as pursuing a “boiling the frog” strategy in Ukraine: introducing more sophisticated weapons gradually, so that Putin wouldn’t leap to nuclear (or other) escalation. Major debates at the time—whether to provide long-range missiles or tanks to Ukraine—may seem overwrought in hindsight, given that no weapon has tripped Putin’s redlines or decisively shifted the battlefield dynamics in Kyiv’s favor. But retrospective armchair strategy is cheap, especially considering that the threat of escalation was very real.

On China, what’s notable is how much of Biden’s hardened posture represents continuity from Trump. Whether export controls on U.S. technology, investment restrictions, or tariffs, the seeds of Biden’s China policy were sown in the Trump years.

The two presidents diverge, however, on Taiwan, which Trump has indicated publicly and privately he cares little about, complaining that Taiwan “took our [semiconductor] business away.” President Biden, meanwhile, has doubled down on Taiwan: hinting on four separate public occasions that the U.S. would come to the aid of the island if attacked, in a deliberate effort—according to Sanger—to “sow seeds of fresh doubt in the minds of the Chinese leadership” that the U.S. would let Taiwan go without a fight.

Perhaps the larger impression from New Cold Wars is that we’ve entered a complex era that eludes an easy through line. The chapters on revanchist Russia, a declining power flailing for imperial restoration in Ukraine, tell a distinct story from those on China, a rising power competing with the U.S. for the commanding heights of the 21st-century economy and supremacy in the Asia-Pacific. The evolving role of cyber-warfare in these rivalries complicates things further (a topic where Sanger shines, as he did in his excellent 2018 book on the subject, The Perfect Weapon).

In short, we’re in for a messier period of, yes, American primacy, but in a more competitive and dangerous environment in which the limits of our influence are clearly visible. Alas, no simple refresh of “containment”—that favorite cliché of foreign-policy types when reaching the limits of their imagination—fits the moment.

Russia and China each present potent and unique challenges, but manageable ones. China, for example, has stumbled economically and now no longer looks 10 feet tall. The real question is whether the U.S., with its roiling and dysfunctional politics, is up to the task.

Theodore Bunzel is managing director and head of Lazard Geopolitical Advisory. He has worked in the political section of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and at the U.S. Treasury Department