Gillian Linden’s beguiling, vexing, and exhilarating debut novel, Negative Space, is a spare, almost austere book, whose unnamed narrator is a teacher at a private school in Brooklyn, a place with high expectations and no grades. Her husband, Nicholas, is a nice enough businessman who is doing well, but not so well that they can actually afford to send their own children to the school where she teaches. Instead, they send the younger of their two kids, Lewis, who seems about five years old, to a less expensive private school, and the older, Jane, seven, to public school.

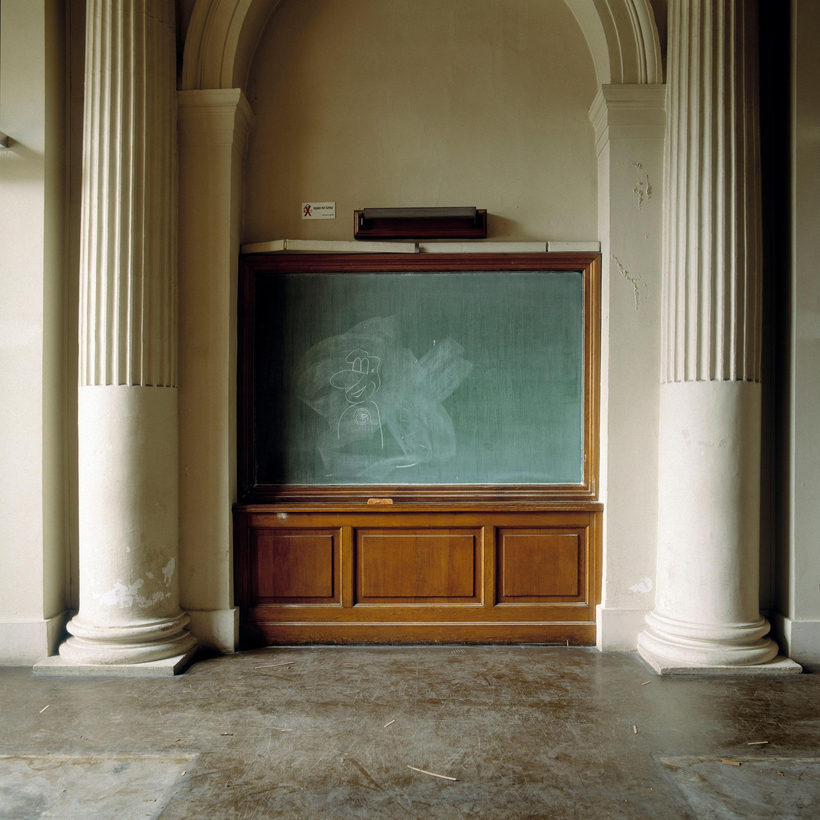

The book takes place over the course of a week in the late-pandemic era, each day its own section, and reads like a series of swift pencil sketches, the sort of drawing that for years hung in my therapist’s office when I was a teenager. There is low-grade marital tension and not-so-low-grade marital tension. Masks are present but often askew. Classes are in-person but some students are on Zoom; the technology is tiring to deal with and no one can hear that well. The narrator’s ninth-graders are reading Kafka.