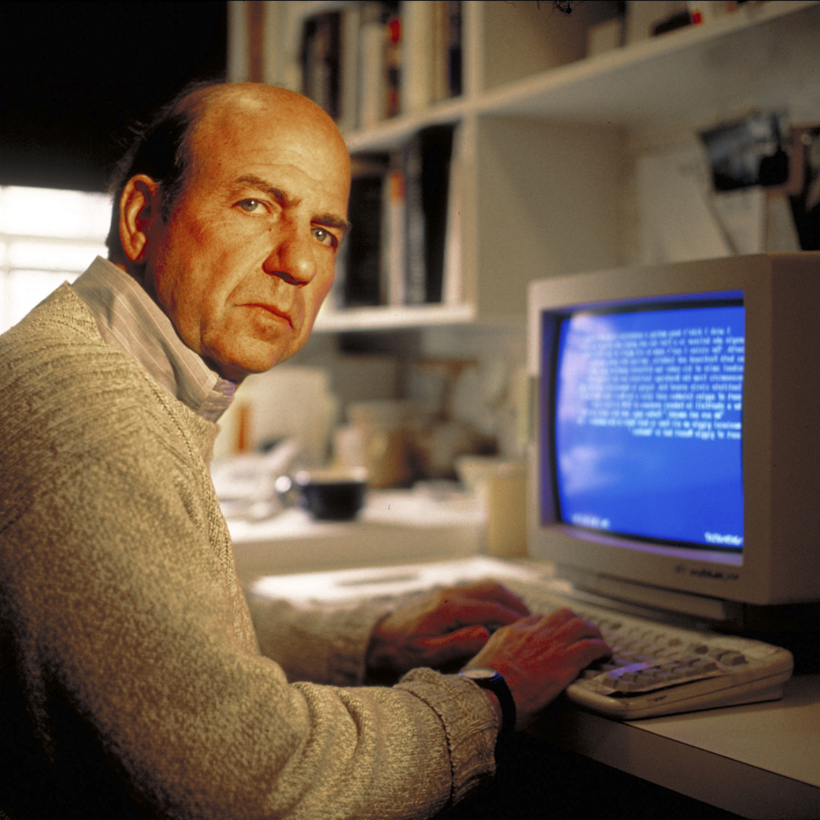

Calvin Trillin is the most wry of writers, though he himself says he long ago decided that reviewers trying to be kind by calling him “wry” really mean “almost funny.” That observation itself is pretty wry, by which we mean “funny, indeed.” He is also a crackerjack reporter and stylist, which makes anything he writes a pleasure to read.

His latest book, The Lede, is a collection of pieces he has written about the press over the past few decades, and taken together they offer as vivid a picture of journalism in the last 40 years as A. J. Liebling did for the profession in the mid–20th century. Plus, Trillin is wryer than Liebling.

JIM KELLY: As a rule, I avoid reading any articles about the proper role of the press in society today or about the endangered state of journalism in an ever changing world. Your book, blessedly, has none of that stuff, but it is a primer of sorts on how to be a first-rate journalist.

One of your best-known pieces in the book is a profile of Edna Buchanan, a Miami Herald police reporter. As you put it, “Edna specializes in murder … and so does Miami.” She also could write a killer first paragraph. Imagine I want to become a journalist. What are the lessons I could learn from Edna Buchanan?

CALVIN TRILLIN: Relentlessness was a serious weapon in Edna Buchanan’s approach to reporting. If the relative of a murder victim angrily hung up on her for the insensitivity of phoning at such a time, she waited 60 seconds—the relative might reconsider; someone more talkative might decide to answer the next call—then called again and said, “This is Edna Buchanan at the Miami Herald. I think we were cut off.”

J.K.: Let me ask that question, prompted by another profile, and dare I say from a much larger angle, that angle being R. W. Apple Jr., the New York Times journalist who wrote some of the most important political stories during the last quarter of the 20th century while at the same time thoroughly enjoying the gastronomic benefits of his paper’s expense account. Indeed, he spent his last years as a food-and-travel writer, pursuing the perfect crab cake with as much energy as he would a State Department scoop. What are the lessons a budding journalist could learn from him?

C.T.: I think Johnny Apple profited from having a deep interest in more than one subject. Essentially a political reporter, he transformed himself in his later years into an authority on culture and travel and, particularly, food. “He’s got a second act,” Ben Bradlee told me. “And he probably has others up his sleeve just in case he eats all the food in the world.”

J.K.: Your profile of Apple itself is a masterful example of how to gently prick the ego of someone enormously talented who would be the first to acknowledge that talent. As you deftly put it, meeting Apple in his maturity, one could be forgiven for thinking “that some time-travel production of The Man Who Came to Dinner had managed to land Sir John Falstaff for the role of Sheridan Whiteside.” How much of a challenge was it to show the reader that a man can be pretentious, highly cultured, overbearing, and worth admiring all at the same time?

C.T.: Showing the two (at least) sides of Apple wasn’t as much of a challenge as it might have been if he hadn’t been so forthright on that subject himself. Discussing the portrait of him by Timothy Crouse in The Boys on the Bus, he said, “Read one way, the book is immensely flattering to me. Read another way, it basically says that I’m an asshole.”

Calvin Trillin is a crackerjack reporter and stylist, which makes anything he writes a pleasure to read.

J.K.: I felt a pang of nostalgia when I read your piece, published in 1978, about a conference of alternative weeklies held in Seattle. A world in which a major city would have one or even two weekly newspapers that specialized in both investigative pieces and angry rants has largely vanished, which I would like to blame on the Internet, but a lot of that vanishing took place long before Twitter was created. Did those papers need a formidable target to survive, such as the Vietnam War or Ronald Reagan, or did they die out because their audiences changed?

C.T.: I agree that the alternative weeklies began their decline before the Internet came along. There are several theories to explain the decline. The one I found most interesting was the rat-through-python theory—the belief that the papers, founded and overwhelmingly read by baby-boomers, reflected the interests and tastes of that “demographic bulge” as single and urban boomers moved through the python toward family life in the suburbs.

J.K.: You wrote a hilarious satire of your days at Time called “Floater.” Those who never had the pleasure of working at a news magazine should know that the title refers to a writer who moves around from section to section, writing about education one week and medicine the next. Not crazy about ending up in religion one week? Well, just insert “alleged” in front of “Nativity” in a story and next week you are writing the People page. Did working at a news magazine hurt or help you as a journalist?

C.T.: I worked for Time in the “group journalism” era, when reports from the field were used by writers in New York to write what ended up in the magazine. Someone just starting out could get experience covering national news stories (in my case, the de-segregation struggle in the South) rather than the local water-board hearing.

It used to be said that Time was a great place for a reporter to work as long as he refrained from reading the magazine. I think the most valuable experience as a Time writer was the constant need for what was called “greening”—the Time term for cutting for space. It made me realize that any piece could be improved by getting rid of, say, 5 percent of it—although I wouldn’t say that within earshot of an editor.

J.K.: John McPhee, a colleague at The New Yorker, published a book last year recounting some of the stories that for one reason or another he never got around to writing. Do you have one or two of those yourself?

C.T.: McPhee is a friend of mine, and I long ago forgave him for being so maddeningly well organized. Offhand, I can think of one piece I should have done—a profile of Bob Moses, who died in 2021. Moses was one of the most fascinating figures to come out of the civil-rights struggle.

“I think the most valuable experience as a Time writer was the constant need for what was called ‘greening’—the Time term for cutting for space. It made me realize that any piece could be improved by getting rid of, say, 5 percent.”

J.K.: You are also a wonderful humorist, but social media and satire do not mix well, as you learned when a poem published in The New Yorker in 2016, poking fun at foodies constantly obsessed about the latest trends in Chinese cooking, led some to call you a racist. The poem’s title alone, “Have They Run Out of Provinces Yet?,” would seem to tip your hand as a humorist. Would Mark Twain be able to make a living in today’s Internet-saturated world?

C.T.: In today’s climate I suppose there would be people criticizing Mark Twain for being offensive to animals in “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” but I think those voices would eventually be drowned out by the applause for Huckleberry Finn.

J.K.: Finally, the desert-island question everyone has been waiting for! You are stranded on said island, and every day a helicopter can drop you either The Washington Post or the New York Post. Which do you choose?

C.T.: Old-fashioned as it may seem, I’d have to get The Washington Post, just to make sure that what I read was the actual news. But I’d miss those New York Post front-page headlines. Many decades ago, when it had a different owner and, therefore, different politics—remember A. J. Liebling’s dictum that freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one?—I worked on a parody edition of the old “knee-jerk liberal” Post. The front-page headline I suggested was COLD SNAP HITS OUR TOWN; JEWS, NEGROES SUFFER MOST. The editor rejected it because there was no story to go with it. That, I maintained, was part of the parody.

Calvin Trillin’s The Lede: Dispatches from a Life in the Press will be published by Random House on February 13

Jim Kelly is the Books Editor at AIR MAIL